The Globalization Of Islam

Since the early 1970s, western Europeans and North Americans have become increasingly concerned about an apparent change in the nature and patterns of human migration. For some this change threatens to alter the ethnic and religious composition of their nation-states, their democratic and capitalist traditions, and their liberal social values. The emigration and settlement of Muslims from more than seventy nations to the West has been of some concern. For those in the West who believe in the purity of race, civilization, and culture, or in a super-sessionist “Judeo-Christian” worldview, this movement of Muslims is a menacing threat to what they believe to be a homogeneous Western society. For others it increasingly represents a significant demographic shift that posits a major cultural challenge, the precise consequences of which are unpredictable and unforeseen, because they require a variety of adjustments by both the host countries and the new immigrants.

Until recently many Europeans and North Americans tended to identify Islam with the Arabs. More knowledgeable scholars added parts of Asia and Africa to the abode of Islam. Other scholars were reluctant to admit that not only is Islam a universal religion with adherents throughout the globe, but that it has increasingly become part and parcel of the West. Ignoring “the facts on the ground,” they persist in thinking of Muslims as displaced persons temporarily residing in the West, who will one day pack up and return to where they came from or to “where they belong.” Still others, who for religious or political reasons wish away these Muslim immigrants, have become more shrill in declaring their presence a threat.

This is the beginning of a larger analysis concerning how globalization and modern migration patterns have influenced and changed the practice and perception of Islam. It also describes the shift in migration flows that began in the 1970s, as well as the rising anxiety experienced among some in Western Europe and North America.

- The End of Post-War Labor Programs. From the 1950s to the 1970s, many European countries used “guest worker” programs to address labor shortages. When these programs ended, many Muslim migrant workers and their families chose to stay in Europe, leading to more permanent settlement and the growth of minority Muslim populations. In the U.S., the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act opened up legal immigration from Asian and Latin American countries that had previously been restricted, leading to greater diversity of immigration.

- The Move Toward Family Reunification. Policies shifted to prioritize family reunification, enabling migrant workers to bring their families to join them in Western countries. This helped transition Muslim communities from being temporary, male-dominated labor forces to more permanent, established communities.

- A More Diverse Origin of Migrants. The migration patterns of this era featured a greater diversity of immigrant backgrounds. Immigrants from different countries arrived in the U.S. and Western Europe with a wide array of skills, from highly-educated professionals to low-skilled laborers.

- The Rise of New Anxieties. The end of these labor programs and new patterns of migration were met with increasing concern in the West. As immigration became a more prominent political issue, politicians often used the image of the “Muslim terrorist” or “foreign criminal” to stoke fear and promote more restrictive immigration policies.

- The Shift in Islamic Identity. The quote also relates to the work of scholars like Olivier Roy, who wrote Globalized Islam: The Search for a New Ummah. Roy argues that the “re-Islamization” many observed in the West was the result of deterritorialization—a globalization that disconnects religious practice from specific cultures. For example, Roy contrasts the new, rootless neo-fundamentalism of some second- and third-generation immigrants with the more traditional Islamist movements in the Middle East.

Islam’s Encounter With The West

Islam’s Encounter With The West

The Muslim encounter with “the West” dates back to the beginning of Islam’s expansion. As Arab armies spread their hegemony over major parts of the Byzantine Empire in Southwest Asia and North Africa, large segments of the Eastern Christian churches (Byzantines, Jacobites, Copts, Gregorians, and Nestorians) came under their control. This close encounter generated a variety of experiences, ranging from peaceful coexistence and cooperation to mutual vilification and armed conflict. It also helped craft a corpus of polemical literature written by both Muslims and Christians, each seeking to demonstrate and proclaim the truth and superiority of their own religion. Each group faulted the other for basing their faith on falsified scriptures as well as proclaiming errant doctrines. The Muslim depiction of the Christian “other” and the Christian depiction of Islam have inevitably been forged by the historical context in which they were conceived.

Muslim expansion from North Africa into western Europe was stopped at Poitiers in 732, but the Ottomans in the East kept probing Europe’s defenses for several centuries until they were halted after the failure of the siege of Vienna in 1683. European areas that came under Muslim jurisdictions in Spain, Portugal, Sicily, and southern France between the eighth and the fifteenth centuries experienced a thriving cultural revival that became a major influence in the transmission of civilization that sparked the European Renaissance. The fall of Grenada in 1492 brought Muslim rule in western Europe to an end. A significant number of the Ottomans continued to live in eastern Europe, where some of the indigenous population converted to Islam in Bulgaria, Romania, Albania, and Serbia. The recent dramatic transplantation of Muslims into western Europe and North America has thus been called “the new Islamic presence.” Other scholars, noting the fact that Islam has modified the religious composition of western Europe and become its second largest religion, have begun to talk about “the new Europe.”

The second major Muslim encounter with “the West” was with Catholic Christianity during the crusades and the Reconquista. Although the crusades took place at the periphery of the Islamic empire and seem to have been concerned with containing and weakening Eastern Orthodoxy as much as Islam, the bloody story of the crusaders sacking Antioch and Jerusalem and slaughtering all the inhabitants is increasingly depicted in today’s Islamic literature as one of Western warriors consumed with Christian hatred, bent on eradicating Muslims and usurping their land. Similarly, the leaders of the Inquisition, armed with the assurance of Christian truth and virtue and in an effort to “de-Islamize” Spain, offered Muslims the options of conversion to Christianity, expulsion, or execution. In the process they all but eliminated the Muslim presence in western Europe, as the last Muslims were expelled in 1609. This phase provides an image of a West not so much interested in guiding Muslims away from their errant ways or debating the efficacy or truth of their beliefs as much as eradicating them. Polemics shifted from issues of errancy of doctrines and supersession to mutual declarations of kufr (unbelief) and apostasy, hence sanctioning violence as a means of restoring truth.

The third encounter is marked by Western colonial expansion into Muslim territory following the fall of Grenada in 1492. In this phase Muslims have encountered the West as a triumphant, conquering, and imperial presence. The colonial experience that initially pitted various European powers against one another in their quest to subjugate Muslims and monopolize their economic resources lasted until after the end of the second world war. By its end Europeans were able to create imaginary lines in the sand, parceling out Muslim territories in a variety of schemes, carving up the three Islamic empires (the Ottoman, Safavid, and Mughal) into what is today some fifty nation-states (members of the Organization of Islamic Conference). Meanwhile, more than one-fourth of the Muslims in the world continue to live under non-Islamic rule.

The colonial experience appears to have left a mark on the consciousness of those who were colonized. Islamist literature increasingly depicts the West as obsessed with combating Islam on all fronts. The West is often portrayed as marshaling its forces to launch a more pernicious attack under the guise of “civilizing” the Muslims and liberating them from “backwardness” and economic dependency, as seeking to subvert the influence of Islam on society by promoting the implementation of certain secular values as the foundation of political, economic, ideological, cultural, and social institutions. Dubbed as a “cultural attack” (al-ghazu al-thaqafi), it is seen as a multifaceted attack launched by colonial bureaucrats and their willing cadre of orientalists and Christian missionaries (both Catholic and Protestant). These bureaucrats and missionaries struggled to cast doubt about Islam by propagating the superiority of Western culture through such colonial institutions as schools, hospitals, and publishing firms, whose goal was to separate the Muslims from Islam.

The current encounter, still in progress, is a by-product of World War II. While this encounter has been conditioned and shaped during the third quarter of the twentieth century by the heritage of the postwar relationships between communism and capitalism, it is also marked by two distinct features. The first is the assumption of world leadership by the United States with the consequent creation and empowerment of the state of Israel and the invention of the “Judeo-Christian” worldview. The second is the emigration and settlement of Muslims and their acquisition of citizenship in the West, in western Europe, as well as in such established regions of European migration as Australia and New Zealand, Canada, Latin America, South Africa, and the United States.

Many types of mosques and community centers have been built in America to serve the large and varied Muslim community there. One of the most elegant is the Islamic Center of New York. Designed by the architectural firm Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill, and located on 96th Street on Manhattan’s tony Upper East Side, it attests to the presence of an international community of Muslims in the metropolis.

Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn

Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn al-Ayyūbī (1138–1193), known in the western world as Saladin, founded the Ayyūbid dynasty and was a highly esteemed Muslim hero of the Crusades. He was born to a family of Kurdish military commanders in the service of the Zangid rulers of Muslim Syria. Although little is known about his formative years, an important turning point in his career came in 1164. The Zangid sultan Nūr al-Dīn had decided to enter the contest for power in Egypt, where the Fāṭimid caliphate was in crisis. Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn accompanied an army destined for Egypt under the command of his uncle, Asad al-Dīn Shīrkūh. Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn was soon able to prove his own valor as a defender of Alexandria against the Frankish Crusaders. In 1169, Shīrkūh became the vizier of the last Fāṭimid caliph, al-ʿĀḍiḍ, but died shortly thereafter, whereupon the vizierate passed to his nephew. Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn then began strengthening his own position, calling several of his family members to Egypt and discreetly undermining the sovereignty of the Fāṭimids.

After the death of al-ʿĀḍiḍ in 1171 and the official end of the Shīʿī Fāṭimid caliphate, Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn ruled over Egypt and its considerable resources, emerging as more than a vassal of the Zangids. Upon the death of Nūr al-Dīn in 1174, he was able to extend his influence beyond Egypt, entering Damascus in 1174 and consolidating his power over the rest of Syria after the death of Nūr al-Dīn’s heir, Ismāʿīl al-Ṣāliḥ, in 1181. This period is the most controversial of his career and some have accused Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn of being a usurper of the Zangids. However, it can also be argued that by uniting Syria under his rule by 1186, he was laying the necessary groundwork for the jihād (holy war) against the Crusaders. To this end, he made appeal to the ʿAbbāsid caliph in Baghdad, thereby strengthening his own legitimacy. Like his former overlord Nūr al-Dīn, Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn’s primary objective was the liberation of Jerusalem, a goal that became realizable after his complete triumph over the Crusader armies at the Battle of Ḥaṭṭīn in 1187. On October 2, 1187, Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn was able to enter Jerusalem, where he peaceably restored Muslim power. His successes, however, stimulated the Third Crusade, and thereafter he was forced to fight a series of campaigns for the cities of Palestine, which drained his military and financial resources and compromised his own health. Upon Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn’s death in 1193, many of his family members were in positions of power in Egypt and Syria, and leadership of the dynasty eventually passed to his brother al-ʿĀdil.

In addition to his military achievements, Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn founded several pious endowments to further the cause of Sunnī orthodoxy. He endowed several madrasahs (legal colleges) in Cairo, as well as a Ṣūfī retreat. He likewise founded several legal colleges in Syria and a madrasah, Ṣūfī retreat, and hospital in Jerusalem; he also restored the Dome of the Rock. It is Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn’s reputation for piety, generosity, and chivalry that has ensured his international and enduring fame.

Reconquista

First coined in the nineteenth century, the term reconquista (reconquest) denotes the gradual and complex process of territorial expansion by which, between c.720 and 1492, the Christian states of the Iberian Peninsula wrested control of the region from Islamic authority. For those who espouse the idea of the “historical unity” of Spain, the reconquista represents a patriotic and religious movement, aimed at restoring the unity of Christian Hispania that had been destroyed by the Islamic conquest of the Visigothic kingdom in 711, and whose outcome was the creation of the modern Spanish state. During the past quarter century, however, scholars have shied away from this overtly nationalistic discourse to emphasize instead the importance of pragmatic politics and socioeconomic forces in driving Christian expansionism.

The reconquista is traditionally considered to have begun in the northern region of Asturias, where in 718 (or 722) a group of Christian rebels led by a refugee Visigothic noble, Pelayo, defeated and killed the local Muslim governor in battle at Covadonga. This Christian enclave survived, and was even able to expand into Cantabria to the east and Galicia to the west, largely because during the 720s and 730s Muslim military energies were focused on southern Gaul. Furthermore, an Arab-Berber civil war in al-Andalus (Muslim Iberia) and North Africa during the 740s, and the severe effects of drought and famine during the 750s, prompted the Berber tribes to evacuate the northern strongholds they had occupied following the Islamic conquest. A century later, renewed turmoil in al-Andalus allowed the Asturian kingdom, under kings Ordoño I (850–866) and Alfonso III (866–910), to advance southward onto the lightly populated plains of the Duero basin, which by then acted as a buffer between the Christian and Muslim territories, and in 910 the chief royal center of the kingdom moved from Oviedo to the old Roman city of León.

Chroniclers viewed the nascent Asturian-Leonese kingdom as the legitimate successor to the Visigothic monarchy and the battle at Covadonga as a divinely guided step towards the Christian reunification of the Peninsula. Political realities were far more complex, however. During the eighth and ninth centuries other centers of Christian power began to emerge in the north. In the Basque territories of the western Pyrenees a realm based in the city of Pamplona — later known as the Kingdom of Navarre — had come into being by the second quarter of the ninth century, despite attempts by Franks and Muslims to bring the region under their respective authority. In neighboring Aragon, another Christian territory came into the orbit of the kings of Pamplona, until it was established as a separate kingdom in 1035. In that same year, the county of Castile, based around Burgos and the Upper Ebro, which had broken away from Leonese overlordship during the late tenth century, also achieved regnal status. At the eastern end of the Pyrenees, meanwhile, in what is now Catalonia, Frankish armies had captured Gerona (785) and Barcelona (802), and established a protectorate, known as the Marca Hispanica (Spanish March), which was ruled by crown appointees. When Frankish power waned during the second half of the ninth century, the counts of the March drifted into independence. However, for the first three centuries after the Islamic conquest, none of the Christian states was powerful enough to challenge al-Andalus for peninsular hegemony. During the tenth century, when the Umayyad caliphate reached the peak of its power, the Christian states were reduced by diplomacy and force to little more than client kingdoms, but there was no attempt to recover the northern territories for Islam.

The eleventh century saw a profound shift in the balance of power in Iberia. Between 1009 and 1031 the caliphate disintegrated, to be replaced by a multiplicity of Islamic city-states (taifas) of varying size and resources. The Christians exploited the endemic political instability and military weakness of the taifas by forcing them to pay sizeable sums in tribute in return for military “protection.” The Christians were also able to make important territorial gains. Most spectacular of all, in 1085 Alfonso VI of León-Castile (r. 1065–1109) conquered the Muslim taifa of Toledo and with it a vast swath of central Spain. Another to profit from the kaleidoscopic political scene was the Castilian noble Rodrigo Díaz, better known as El Cid, who conquered the taifa of Valencia in 1094. The fall of Toledo sent shock waves throughout al-Andalus, prompting the Almoravids, a Berber Muslim sect, to intervene and defeat Alfonso VI in battle near Badajoz in 1086; they subsequently brought the remaining taifas under their authority.

The wars of the late eleventh century rekindled the ideology of reconquista, itself further sharpened by the introduction of the ideas and institutions of crusade. Encouraged by papal pronouncements, which began to equate the Iberian campaigns against Islam with the crusading expeditions to the Holy Land, the idea that military activity against Muslims had a penitential value took root in the Peninsula. It was thus with contingents of foreign crusaders that Alfonso I of Aragon (r. 1104–1134) conquered Saragossa in 1118; Alfonso VII of León-Castile (r. 1126–1157) seized Almería and Afonso I, the first king of Portugal (r. 1128–1185), captured Lisbon, both in 1147; and Ramón Berenguer IV (r. 131–1162) of Aragon-Catalonia captured Tortosa and Lérida in 1148 and 1149, respectively. The crumbling of Almoravid authority in al-Andalus and North Africa facilitated the Christian advances of the 1140s, but further expansion into the area south of the Tagus and Ebro rivers was hindered by infighting among the Christian states and the arrival of a new Berber power in al-Andalus, the Almohads. During the second half of the twelfth century, the Almohads launched numerous attacks against Christian positions and inflicted a major defeat on Alfonso VIII of Castile (r. 1158–1214) at Alarcos in 1195. However, the southern Christian frontier was bolstered by the foundation of a number of indigenous military orders — particularly those of Calatrava (1158), Santiago (1170), and Alcántara (1176) — and by the expertise of the local town militias, whose raiding expeditions devastated the economy of the exposed Muslim communities to the south. In July 1212, Alfonso VIII, with papal backing and Navarrese and Aragonese support, crushed the Almohads at Las Navas de Tolosa and opened the road to southern Spain.

Christian fortunes were further assisted by the death of the Almohad caliph Yūsuf II (1213–1224), which prompted an intense struggle for power within the ruling dynasty. As Almohad authority crumbled during the 1220s, a new generation of taifas emerged to fill the power vacuum and the Christian states, furnished with fresh crusading indulgences, went on the offensive. To the east, James I of Aragon (r. 1213–1276) conquered the Balearic Islands (1229–1235) and overran the taifa of Valencia (1232–1245). To the west, Alfonso IX of León (r. 1188–1230) annexed what is now Spanish Extremadura, conquering Cáceres (1227) and Mérida and Badajoz (1230). His son Fernando III (r. 1217–1252), who reunited León and Castile in 1230, advanced down the Guadalquivir valley, capturing Córdoba (1236), Jaén (1246), and Seville (1248), and receiving the submission of the kingdom of Murcia in 1243–1244. In the far west, the Portuguese fulfilled their own territorial ambitions by occupying the Algarve in 1249. By the mid-thirteenth century, Muslim authority in Iberia had been extinguished with the exception of the Nasrid emirate of Granada and a handful of puny enclaves on the Atlantic seaboard. That Granada was able to maintain its independence thereafter owed much to its readiness to buy peace from Castile in return for tribute, to the political turmoil which regularly convulsed the Christian states, and the Nasrid rulers’ skill in shifting allegiance between Castile, Aragon, and the Berber Marinids, the dominant power in North Africa. Castilian military operations thereafter focused on controlling the ports that dominated the Straits of Gibraltar. Thus, Sancho IV (r. 1284–1295) captured Tarifa in 1291 and Alfonso XI (r. 1312–1350) reinforced that control by defeating the Marinids at the River Salado in 1340 and by conquering Algeciras in 1344.

Thereafter, the conquest of Muslim Granada ceased to become a pressing objective for Castile, as dynastic wars, as well as famine and epidemics, took their toll. It was not until the reigns of Isabella I of Castile (r. 1474–1504) and her consort Ferdinand II of Aragon (r. 1479–1516), who both saw a campaign against Granada as an opportunity to instill loyalty to the monarchy, that the final act of the reconquista was played out. Encouraged by dynastic infighting within the Nasrid royal house and supported by new crusading indulgences, massive subsidies from the Church, and the arrival of foreign volunteers, the Christian forces engaged in a ten-year war of attrition leading to the fall of Granada in January 1492. Even with Islam defeated, the ideology of the reconquista continued to be felt. It contributed to the increasingly sectarian attitude toward Muslims, Jews, and Moriscos (Muslim converts) that characterized sixteenth-century Castilian society, just as it also fueled Spanish imperial ideology, which saw the creation of an overseas empire — in the Americas and elsewhere —as the fulfillment of the manifest destiny of Christian Spain foreshadowed centuries before. (For more on the Reconquista, see: https://discerning-islam.org/802-042-reconquista/).

The Cultural Divide

The scramble to identify the next threat to Western democracies that ensued after the fall of communism has not yet abated. Islam and Muslim culture have been depicted by certain interests in the United States as the next challenge, if not the enemy challenging the West. It is accused of being a religion that is devoid of integrity and progressive values, a religion that promotes violent passions in its adherents, a menace to civil society, and a threat to the peace-loving people of the world. Muslims are often cast as bloodthirsty terrorists, whose loyalty as citizens must be questioned because they are perceived to be obsessed with the destruction of the West.

Samuel Huntington’s publication of “The Clash of Civilizations” in Foreign Affairs, promoting a thesis that the next conflict will not be between nation-states or ideologies but civilizations, appears to have gained support among some policy pundits. His thesis has reconfirmed to Muslims that colonialism is not over, because it has echoes of themes heard since the nineteenth century. On the surface it appears as a rehash of a century-old myth that undergirded European hegemonic policies justifying wars of colonial expansion and missionary crusades during the nineteenth century under the rubric of “civilizational mission,” “white man’s burden,” or Manifest Destiny. It posited the superiority of European man, the acme of human civilization, who willingly assumes the burden of sharing his values and achievements with the rest of the backward world. In the process, this myth justified the ransacking of the cultures of the conquered people and confining Muslim achievements to ethnological museums or the dustbin of history.

Meanwhile, the immigrants bring with them a different understanding of their culture. Many believe that they have been victims of Western cultural hegemony. For them the preservation of distinctive culture is the last line of defense against total obliteration. Battered by Western weapons of destruction, overcome by Western scientific achievements, and reduced to vassal states, Muslims have been attempting to resist by hanging on to Islamic civilization as the last bastion of human dignity and worth, a means of galvanizing people and keeping them from total disintegration. Consequently, conformity to Islamic culture, traditions, and norms is not only a source of pride in Muslim contributions to human civilization, it has become a divine imperative, a cure for what ails Muslim society and the world. It is promoted as possessing redemptive powers. Public performance of the rituals of Islam and maintaining a distinctive culture has thus become a vehicle of healing. Deviating from the consensus of what is publicly considered normative by the majority population in which the immigrants live is not backwardness; rather, it is a willful act of coherence and an option of a more meaningful reality. In the process, for some, ritual has become an instrument of protest against a society that continues to treat Islam as an alien religion whose adherents are fixated in the seventh century.

The Rise Of Islam And The Major World Religions To 1500 AD

The major religious tradition to arise was that of Islam. After the migration (Hejira) of Muhammad from Mecca to Medina in 622 AD, he became the overall leader of the whole city of Medina, and Islam began a dramatic expansion. By 661 AD, during the golden age of Muhammad and the four early caliphs, Islam had spread through much of North Africa and the Middle East, the Qur’an had been finalized, the Arabic language had begun to permeate what became the Arab world, and Islam was poised to expand still further.

By 1258 Islam had penetrated into Spain in the west and India in the east and was at least equal in strength to Europe, India and China.

The Great Religious Traditions

Christianity spread within Europe, absorbing the various northern tribes, including the marauding Vikings; and with the rise of Russia its Orthodox branch began to venture east into the steppes. Islam ventured into Europe, reaching Spain in the west and, eventually, Turkey in the east. In early Spain creative contacts developed between the Christian, Muslim and Jewish communities. Elsewhere, on the other hand, the Crusades exacerbated the sense of hostility between Christians and Muslims.

Islam became established in India through the medium of the Mughal empire, which had also received Syrian Christians, some Jews, some Parsis (who settled in Bombay after fleeing from the Muslim invasion of Persia) and later the Sikhs. All these groups co-existed with India’s majority Hindus, Jains and Buddhists (who virtually died out in later medieval India). In China the neo-Confucian revival, centered on Chu Hsi ( 1130 – 1200 ), incorporated elements of Daoism and Buddhism, and in Southeast Asia Buddhism grew in strength. European Christendom became the most beleaguered of the four major religions, beset by Islam to the south and Tartar and Mongol hordes to the east. Within Europe, except for early Spain, the Jews were spasmodically persecuted.

Parallel Religions

Although the four major religions were radically different, some linking patterns can be discerned. Transcendence, and the means by which it was achieved, mattered; whether it was seen in terms of reaching Allah through Christ, Allah through the Qur’an, a Hindu personal deity through the mediation of a Brahmin, or the enlightened state of Nirvana through the Buddha or the Dharma (the Buddha’s transcendent teaching). The monastic or mystical communities of each tradition encouraged the development of inward spirituality. In all four religions, the future life, whether in heaven or beyond the round of rebirths, mattered as much as, if not more, than this life. In the Christian world, theological and philosophical syntheses of faith emerged in the work of Aquinas and Bonaventura in around the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. These syntheses were echoed by Maimonides in the Jewish world, al-Ghazali in the Muslim world, Chu Hsi in China, and Ramanuja in India.

Each tradition saw the development of different branches of the faith; Catholic and Orthodox Christianity, Sunni and Shi’ite Islam, Theravada, Mahayana and Tibetan Buddhism, and Hindu communities centered specifically upon Siva, Visnu and the Allahdess. All of the traditions were distinguished by elaborate rituals, festivals and sacraments, great ethical systems, and beautiful buildings, sculpture and literature.

In the wider world the American Indians, the Inca and Aztec cultures, the peoples of southern Africa, the Aborigines of Australia, the Maoris of New Zealand, and the peoples of Oceania were cut off mainly by sea from the classical traditions, as were the peoples of Siberia and the Arctic, through the exploits of Mongol invaders.

Historiography

The modern‐day historians of the Islamic world, particularly those of the Middle East and South Asia, are the heirs of a powerful and sophisticated tradition of historical writing, and they appeal to (or feel the burden of) this tradition on many levels. Historical writing was one of the earliest and most highly developed literary genres in every region and language of the Islamic world. The characteristic formal structures, subject matter, and explanatory paradigms of this literature took shape between the early eighth and eleventh centuries, and persisted — with much flexibility and elaboration but little change at a deep level — down to the early nineteenth century. By the 1840s, however, the forms and perspectives of traditional historiography, rich and varied as they were, no longer seemed adequate in face of the radical challenges posed by Europe to every aspect of life in the Islamic world. By the beginning of the twentieth century, a few historians were beginning to model their work (with mixed but not inconsiderable success) on European approaches and research methods. The 1910s and 1920s witnessed the founding of universities on the European model, and as an inevitable consequence, a growing professionalization of history. That movement has continued down to the present, so that now (as in Europe and America) the writing of history has become largely an academic enterprise, with all the gains and losses that this implies.

The evolution of historiography throughout the entire Islamic world cannot be followed in a brief article. Therefore, the focus will only cover three areas: the central and eastern Arab lands (with an emphasis on trends in Egypt), Turkey, and Iran. Historiography in India and Pakistan on the one side, and North Africa on the other, has not developed in isolation from the Middle East; on the contrary, the parallels and mutual influences have been close and profound. But historical writing in these countries has followed a distinctive path, shaped by a far tighter (even suffocating) colonial domination, and marked by a clear preference for English and French (rather than Arabic or Urdu) among the leading modern historians.

Islam In The 19th Century

The challenge of Europe was of course felt most immediately in political and economic life, but that in itself might have compelled few changes in historical vision; Muslim intellectuals had faced many equally acute crises on this plane over the centuries, and the deeply rooted but still flexible conceptual tools and cultural resources of their societies had permitted them to address these quite effectively. The European cultural challenge cut deeper, however. Felt only by a tiny minority as late as the mid‐nineteenth century, it had become inescapable to almost everyone (at least in the major urban centers) by the beginning of the twentieth. Not only did it threaten the political independence and economic autonomy of Muslim societies; it assailed the very foundations of Muslim identity.

The rapid intellectual readjustments of the late nineteenth century (down to World War I) of course affected historical writing, although the works produced in this genre do not reach the level of the political and cultural essays of Rifā῾ah Rāfi῾ al‐Ṭahṭāwī (1801–1873), Namik Kemal (1840–1888), Jamāl al‐Dīn al‐Afghānī (1839–1897), or Muḥammad ῾Abduh (1849–1905). This is probably due in large part to the fact that history continued to be (as it always had been in Muslim countries) the work of amateurs, and moreover was seldom attempted by the leading intellectuals of the age. As one might expect, the shift toward new forms and approaches began in Cairo and Istanbul, the two largest cities in the region, the seats of the most ambitiously reformist regimes, and the places most directly and profoundly exposed to Western pressures.

Cairo was the first and most important center of a changing historiography. It had in fact produced the last great work in a traditional mold, the ῾Ajā’ib al‐āthār of ῾Abd al‐Raḥmān al‐Jabartī (1753–1826). Al‐Jabartī witnessed the catastrophic self‐destruction of the Mamlūk regime in the late eighteenth century, the shock of the French occupation in 1798–1801, and the tumultuous changes forced on the country by Muḥammad ῾Alī (r. 1805–1848). He was an acute observer, but he regarded none of this as progress, and he was content to work within the chronicle/biographical dictionary framework bequeathed to him by the great Egyptian historians of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

Muḥammad ῾Alī, illiterate soldier that he was, had more than a little to do with the rise of an altered historical consciousness. Quite apart from his military, administrative, and economic initiatives, so disruptive of deep‐rooted institutions and habits of thought, he took the risk of sending student missions to study in France, thereby exposing at least a few of his subjects to the thought and culture of contemporary Europe. No less important was his founding of the Translation Bureau (under the directorship of al‐Ṭahṭāwī), which rendered many works of medicine, engineering, geography, and even history into Turkish and Arabic. To be sure, the few historical works chosen for translation (e.g., Montesquieu’s Considérations sur les causes de la grandeur des Romains et de leur décadence, or Voltaire’s lives of Charles XII and Peter the Great) represented the Enlightenment, not the new scientific history of Ranke or the romantic nationalism of Michelet; even so, they suggested radically new ways of imagining and representing the past.

The first major history in Arabic to reflect new possibilities and tensions was Al‐khiṭaṭ al‐tawfīqīyah al‐jadīdah (20 vols., Cairo, 1886–1888) by ῾Alī Mubārak (1824–1893), the engineer who oversaw Khedive Ismā῾īl’s ambitious revamping of Cairo in the 1860s and early 1870s. Modeled to some degree on the classic work by Taqī al‐Dīn al‐Maqrīzī (d. 1442), it is a remarkably rich miscellany of historical‐biographical information, geographical description, and administrative data. Conceptually and structurally conservative (like al‐Maqrīzī’s work, it is organized by toponym), its contents never‐the-less reflect many aspects of the new order. A hybrid work of this kind could not generate many successors, although the Taqwīm al‐Nīl (6 vols., Cairo, 1916–1936) of Amīn Sāmī (c. 1860–1941) comes closest in spirit and content. Like al‐Ṭahṭāwī and ῾Alī Mubārak, Sāmī spent his life in loyal service to the regime, chiefly as an educator; he was director of the government teachers’ college, Dār al‐῾Ulūm, under Tawfīq and ῾Abbās II, and was appointed to the Senate by King Fu’ād.

In Egypt the political and ideological crisis of the ῾Urābī period proved in the long run to be a turning point, but for a time one sees only limited results — owing in large part to the stifling of political life under Lord Cromer until almost the turn of the century. An exception to this generalization would be Salīm al‐Naqqāsh’s passionate, richly detailed, but still little‐studied history of the ῾Urābī Revolt, Miṣr lil‐Miṣrīyīn (6 vols., Alexandria, 1884), based heavily on government documents and trial proceedings. By the end of the century we can perceive a marked shift from neo-traditional to contemporary European models of historiography. Of the new historians by far the most successful and widely read was the staggeringly prolific Syrian immigrant Jirjī Zaydān (1861–1914). He edited several journals and wrote in many genres; among his works the most significant in the present context is his Tārīkh al‐tamaddun al‐Islāmī (5 vols., Cairo, 1902–1906). This is less an original work of scholarship than a popular synthesis derived in large part from European Orientalist scholarship; even so, it is a very competent job and earned an English translation of one volume (Umayyads and Abbasids, London, 1907) by the formidable David Margoliouth. Zaydān’s was thus the first Arabic work in “modern” style to address medieval Islamic history. It was widely read but not much emulated, perhaps because as a Christian committed to a westernizing approach, Zaydān could not address adequately the deeper issues raised by his subject for modern Muslims. Nor could he really share the aspirations and frustrations of Egyptian nationalist writers. He was in fact offered the position in Islamic history at the new Egyptian University in 1910, but outrage in politically engaged circles compelled the offer to be withdrawn.

Istanbul was the home of a rather different historiographic evolution. It was still the capital of a vast empire, ruled by an autocrat who increasingly defined his role in terms of the Islamic caliphate. Moreover, its historians continued to be, as for centuries past, part of the scribal‐bureaucratic elite whose careers and personal identities were closely linked to the fortunes of the Ottoman state. A strongly conservative trend is thus no surprise in the two leading historians of the mid/late-nineteenth century — Ahmed Cevdet Pasha (1822–1895) and Ahmed Lutfî Efendi (1816–1907), both of whom were official court historians (vakanüvis), the last men to hold that post under the Ottoman sultans. Both recognized the changes going on all around them, but Lutfî resisted them, while Cevdet Pasha exhibited a more realistic mentality. Lutfî, for example, drew heavily on the official gazette for his information on the Tanzimat decades — a method that ensured a narrow, superficial, and highly laudatory account of this critical period (Tarihi Lutfî, 8 vols., Istanbul, 1873–1910; the final volumes remain unpublished). Cevdet Pasha, in contrast, had a strong grasp of law and administrative institutions and was deeply concerned with the processes governing the decline and fall of states. He was several times Minister of Justice and of Education and occasionally acted as a provincial governor (usually in Syria). He was the editor in chief of the Mecelle (the sharī῾a‐based code of civil law issued between 1870 and 1877) as well as a translator of Ibn Khaldūn. Although his chronicle of the crucial half‐century between 1774 and 1826 (Tarihi vekayii devleti âliye, 12 vols., Istanbul, 1885–1892), composed over a period of some thirty years, is traditionally constructed, it makes considerable use of European as well as Ottoman documents. Apart from Cevdet and Lutfî, we should mention the several historical works of the leading Young Ottoman intellectual Namık Kemal, a far more progressive spirit than his two older contemporaries. But his historical writings (many either never published or quickly suppressed) were hastily written inspirational and patriotic exercises and had almost no impact on the development of modern Turkish historiography.

The old mold was broken first by the Young Turk seizure of power in 1908, and then, decisively, by the Kemalist revolution. Whatever his defects as a thinker and politician, Ziya Gökalp (1875–1924) brought contemporary European sociology and history into the mainstream of Turkish intellectual life, where it found a ready reception. After World War I, Atatürk’s generation would create modern Turkish historical writing. (See Section 200 – Biographies – Ziya Gökalp; https://discerning-islam.org/405-007-a-biographies-mehmet-ziya-gokalp/).

Nineteenth‐century Iran did not witness the deep intellectual transformations of Cairo and Istanbul; the country’s poverty and isolation, not to mention the political ineptitude of the Qājār court, left its historians working in a traditional framework (albeit enormously sophisticated) until the turn of the century. The Constitutional Revolution (1905–1911) was the culmination of a long process, and it would be misleading to attribute the later explosion in Persian intellectual life solely to this cataclysmic event. Yet the Revolution did crystallize the new currents of thought in the country, still illformed and shallow‐rooted before 1905. It also created a powerful myth of promise, betrayal, and struggle for redemption — a myth that continues even now to shape many realms of Iranian life.

Islam In The 20th Century

Inter-war Period: 1919-1945

World War I was the turning point in almost every aspect of Middle Eastern life; indeed, this titanic event really laid down the agenda for the entire twentieth century within the region. It created vast new hopes and possibilities, and of course even more bitter disappointments and insoluble problems. It is no surprise that it ushered in a new era of historical writing marked by several characteristics: growing, if far from complete, professionalization (with several scholars getting doctorates in Europe, especially from Paris), institutionalized within the new universities of Cairo, Istanbul, and Tehran; a much closer approximation in form and methodology to the kinds of historical writing practiced in Europe; and a definition of persistent subject‐matter areas, somewhat different for each of the linguistic/cultural realms. One apparently odd product of the period was a marked bilingualism among the new generation of historians, who often wrote in French or English for European audiences, and in Arabic, Persian, or Turkish for their own countrymen; in the latter works the cultural agendas and conflicts of their native countries came to the fore. This phenomenon continues strongly in the present.

It would be incorrect to assume that all traces of traditional literary‐historical culture disappeared during these two decades. On the contrary, some of the most significant and useful historical compositions adhere to long‐established genres. Thus Osmanlı devrinde son sadrazamlar (Istanbul, 1940–1949) is an invaluable biographical compilation on the last thirty‐seven Ottoman grand viziers by Ibnülemin Mahmut Kemal Inal (1870–1957), himself a senior bureaucrat in the empire’s final decades and a scholar steeped in all aspects of Ottoman literary culture. Another writer, Muḥammad Kurd ῾Alī (1876–1953), the founder of the Arab Academy of Damascus and a prolific journalist and littérateur, composed a monumental history of Syria, Khiṭaṭ al‐Shām (6 vols., Damascus, 1925–1929). Although Kurd ῾Alī was well acquainted with the critical methods of Western Orientalism, this is the last great work of historical topography, a Syrian tradition going back to Ibn ῾Asākir (d. 1176) that flourished at least until the eighteenth century.

Works of more “modern” style tended to reflect in quite direct ways the central contemporary political‐cultural debates of the countries in which they were written. This was true not only of works on recent history, but of those dealing with the more remote past. Indeed, the segments of the past chosen for discussion provide an excellent index of these debates. In Egypt, attention was focused equally on the nineteenth century (especially Muḥammad ῾Alī, Ismā῾īl, and the ῾Urābī Revolt) and on the beginnings of Islamic history. On the nineteenth century, the key works were probably those written by ῾Abd al‐Raḥmān al‐Rāfi῾ī (1889–1966), Muḥammad Ṣabrī (1894–1978), and Shafīq Ghurbāl (1894–1961). Al‐Rāfi῾ī, an ardent partisan of the old National Party founded by Muṣṭafā Kāmil at the turn of the century and deeply immersed in Egypt’s political struggles, was self‐taught as a historian and wrote exclusively in Arabic. Ṣabrī and Ghurbāl were professional academics; both took doctorates from the Sorbonne, held chairs at Cairo University, and published much of their major work in French or English.

In regard to early Islamic history, Ṭāhā Ḥusayn’s Fī al‐shi῾r al‐jāhilī (Cairo, 1926), Muḥammad Ḥusayn Haykal’s Ḥayāt Muḥammad (Cairo, 1934), and Aḥmad Amīn’s three books on early Islamic history (Fajr al‐Islām, Ḍuḥā al‐Islām, and Ẓuhr al‐Islām, Cairo, 1928–1953) are landmarks in their various ways. Ṭāhā Ḥusayn had taken a Sorbonne doctorate with a thesis on Ibn Khaldūn; his attack on the authenticity of pre‐Islamic Arabic poetry was an effort (almost disastrous for him and Cairo University) to apply European textual criticism to a culturally sanctified body of literature. The works of Haykal and Amīn, in contrast, were attempts to synthesize Islamic piety and “scientific” historical method. However one judges Haykal’s use of modern critical methods, his biography of the Prophet was a literary tour de force, a superbly integrated portrait infused with a distinctively twentieth‐century sensibility. Aḥmad Amīn’s studies, though less accessible, have commanded broad respect since their first publication. Although he was a graduate of the School for Qāḋīs and was largely self‐taught as a historian, his European colleagues at Cairo University formally recommended him for a professional chair on the strength of his publications.

In Turkey scholars followed Atatürk’s lead by turning their backs on the recently‐extinguished Ottoman Empire in favor of an older, more “authentic” Turkish history, in particular Central Asia and the Seljuks. Here the leading figures were two exact contemporaries. Zeki Velidi Togan (1890–1970) was an emigré from Russian Turkestan and devoted his life to the history and literature (both medieval and modern) of the Turkic peoples of Central Asia. Mehmet Fuat Köprülü (1890–1966), a descendant of a famous seventeenth‐century vizierial family, was essentially an autodidact, but he became the most influential scholar of his generation in Turkish literature and the history of the Seljuks of Anatolia. He published mostly in Turkish, but his 1935 lectures in Paris, Les origines de l’Empire Ottoman, marked a turning point in the study of that controversial subject.

In Iran work was inevitably affected by the neo‐Achaemenidism and anti‐clericalism of the Reza Shah regime; the historiography of this era, though by no means always royalist in tendency, was deeply nationalist and often anti‐clerical. These trends are perhaps most tellingly summed up in the writings of Aḥmad Kasravī (1890–1946). Born in Tabriz, politically the most progressive and cosmopolitan city in Iran at the turn of the century, and trained as a cleric, he abandoned that path by the age of twenty. In the early years of the Reza Shah era he served as a judge and lawyer and then taught history at the University of Tehran, but in 1934 he left these official careers for one as a journalist and cultural critic. His vitriolic attacks on Shi’ism and Iranian cultural traditions earned him both a devoted following and deadly hostility; his assassination by the Fidā’īyān‐i Islām was almost predictable. He was, when he set his mind to it, a talented historian. An early work, Shahriyārān‐i gumnām (Forgotten Rulers, 3 vols., Tehran, 1928–1930), deals with the pre‐Seljuk dynasties of his native province and is still regularly cited. His most important work, however, was on the Constitutional Revolution (Tārīkh‐i mashrūṭah‐i Īrān, 3 vols., Tehran, 1940–1943), in which he had participated as a youth and in which his native city of Tabriz had played a critical part. [See Section 200 – Biographies – Aḥmad Kasravi.]

The leading historians of this period did not simply toe the official line. On the contrary, many of them were opponents of the new governments and often in trouble with them. Nor is their work merely a coded statement of their own ideological predilections, for the work of every writer mentioned above has proved of enduring value. Al‐Rāfi῾ī’s books, for example, have been regularly reprinted down to the present. But it remains the case that all these works were shaped in the context of the political struggles of their day, including the struggles for cultural identity as Egyptian, Turk, Iranian, or Muslim.

The Cold War And Middle Eastern Nationalism: 1945-1970

World War II marked another watershed as the domination of the region by Great Britain and France collapsed, to be replaced by a bipolar world of American‐Soviet rivalry. At least until the early 1970s, and in some arenas until the present, intellectuals in the Arab lands and Iran tended to interpret their past within a single broad framework, as a struggle against foreign domination — by England and France in the modern period, of course, but often by fellow (Mamlūk amirs, Arab invaders, and so on) in the medieval past. In the revolutionary age beginning in the mid‐1950s, it was inevitable that many would also begin to look seriously at Marxism as an intellectual tradition, and thus to link issues of internal class struggle with long‐established concerns about imperialism. Muslims

Turkish intellectual life moved along a somewhat different path. There the Atatürk revolution had successfully forestalled direct foreign domination. Likewise, while the Atatürk regime’s étatist and autarchist policies may well have limited Turkey’s economic growth, they also reduced concern over covert foreign influence, at least until the late 1960s, when a rise in anti‐Americanism was provoked in part by the repeated crises over Cyprus. Marxist interpretations did, however, speak to the pervasive poverty of the Turkish countryside and the frustrations of an emerging working class in the major cities.

The inevitable engagement of historians in the political struggles of the postwar years did not prevent the increasing professionalization of historical writing. The process was rooted in the rapid growth of higher education in Middle Eastern countries: a flood of new students into the universities required more professors, and professors had to have advanced research degrees. Down to the early 1970s credible Ph.D.s could only be obtained abroad, preferably in Paris or London (the old imperial capitals, ironically), but many students found themselves in newer and less prestigious institutions in the north of England or the American Middle West. The bilingual nature of historical research among Middle Eastern scholars continued and even increased; many of the major French and English monographs published during these years had begun life as doctoral theses at the Sorbonne or the University of London.

Again, it would be extremely misleading to interpret scholarly production simply as a reflection of ideology and political conflict. If a test for the “pure scholarship” of a work is its usability by scholars of disparate political‐ideological commitments, then much produced in this era must rank very high indeed. To take only the most eminent names, it is hard to imagine modern Ottoman studies without Halil Inalcık, or early Islamic history without ῾Abd al‐῾Azīz al‐Dūrī. [See the biography of Dūrī.] The study of Seljuk history became a favored preserve of Turkish scholarship, and the collective contribution of Osman Turan, Mehmet Köymen, and Ibrahim Kafesoğlu probably outranks work on this subject done anywhere else in the world. In spite of political controls placed on Egyptian scholars under the Nasser regime, the students of Muḥammad Anīs at Cairo University initiated a major body of scholarship on the social and economic history of nineteenth‐ and twentieth‐century Egypt. For an earlier but hardly less contested era, that of the Crusaders, Ayyūbids, and Mamlūks, Sa῾īd ῾Abd al‐Fattāḥ ῾Āshūr and his many students produced (and continue to do so) a major corpus of texts and studies still too little consulted among Western scholars. Even so, the free play of historical research was undeniably constrained by political pressures that far exceeded the partisanship of the previous era, notably the internal security apparatus of Nasser’s Egypt and Muhammad Reza Shah’s Iran, the unpredictable violence of political life in Syria and Iraq, the intermittent military interventions in Turkey, and the taboos inspired by the Arab‐Israeli conflict.

From 1970 to 2000

Several of the underlying trends established during the 1950s and 1960s have continued apace, in particular the burgeoning of universities and research institutes throughout the Middle East. In spite of chronic underfunding and a strong emphasis on scientific‐technical training, this trend has led to an expansion of academic history. Particularly important, especially for the Ottoman period in Turkey and the Arab lands, has been a great improvement in the organization of archives and documentation centers of all kinds. (Unfortunately, Iran seems not to have benefited from such a process under either the shah or the Islamic Republic.) Another trend, already discernible before 1970 but much stronger since, has been the growing number of historians from the Middle East who hold permanent academic appointments in Europe and the United States. Admittedly, most of these completed their graduate studies in Western universities, but even so they bring a perspective rooted in the cultures and historical experience of the Middle East.

The political climate in which historians must try to work has been variable. Egypt has witnessed an unsteady but substantial liberalization; in contrast, Syria and Iraq have moved from instability to tightly regimented dictatorships. Turkey has experienced a cycle of almost chaotic openness, severe military censorship, and, since the mid‐1980s, a gradual easing; however, it remains illegal to criticize Atatürk, which inevitably constrains work on the crucial quarter‐century from 1914 to 1938. In Iran, the Islamic Revolution has opened up certain possibilities for research while closing others; historians of a secularist orientation have obviously had to choose their topics and their words with great tact. In general, the Islamic movement everywhere has increasingly affected historical inquiry and writing, as it has intellectual life in general. For example, a trend seen in the Arab world during the early 1970s — a radical critique of the nature of early Islamic society and even of the soundness of the sources — has been silenced or at least driven underground. There has been no real progress in Arabic‐language works on the life of Muḥammad since Haykal’s famous biography was published more than sixty years ago.

In spite of such official and cultural pressures, however, many periods and topics seem to be politically and religiously neutral, in the sense that historians are relatively free to construct their accounts of them in accordance with their own purposes and outlooks rather than externally‐dictated agendas. The middle periods of Islamic history (c. 900–1500) have long fallen in this category, with the partial exception of the Crusades and the figure of Saladin, and we can now add the early ῾Abbāsids and the Ottoman era, no longer a useful target for Arab nationalist polemics. The social and economic history of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in particular has attracted a great deal of first‐rate work during the past two decades. In premodern times, the early ῾Abbāsids, the Seljuks, and the Mamlūks have continued to be the subject of valuable and sometimes ground‐breaking studies. To name individual scholars for the last two decades seems invidious, since there are now so many historians at work, and it is hardly possible as yet to identify those whose contributions will prove seminal or enduring. What can be said is that there now exists, in all the major countries of the Middle East, a substantial corps of professional academic historians writing chiefly in the languages of the area. In this respect, the history of the region is increasingly in the hands of its own scholars — the natural state of things, we might suppose, but one that was hardly the case for most of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Islam In The 21st Century

The Migration of Islam After 9/11

The September 11, 2001 attacks did not initiate a migration of Islam, but rather dramatically reshaped the migration patterns, experiences, and treatment of Muslims and people from Muslim-majority countries. It intensified pre-existing immigration restrictions, fueled anti-Muslim sentiment and discrimination, and contributed to new waves of forced displacement.

Impact on Immigration and Migration

Stricter Immigration Policies and Enforcement

- Targeted Enforcement: In the U.S., post-9/11 policies aggressively targeted Muslim, Arab, and South Asian communities, leading to mass detentions and deportations for minor infractions. Programs like the National Security Entry-Exit Registration System (NSEERS) required adult males from 25 predominantly Muslim countries to undergo mandatory registration and interviews.

- Reduced Admissions: Following the attacks, the U.S. temporarily halted refugee admissions. While the system was later rebuilt, the refugee cap was reduced and security measures were heightened, making it harder for people from Muslim-majority nations to resettle. This trend was further amplified during the Trump administration.

- Visa Restrictions: Student visas and other forms of labor migration became significantly more difficult to obtain. New screening processes like the Student and Exchange Visitor Information System (SEVIS) were implemented to track foreign students.

Intensified Discrimination and Fear

- Bias Crimes and Harassment: The initial aftermath saw a sharp rise in hate crimes and discriminatory incidents against those perceived to be Muslim, including Arabs, Sikhs, and South Asians. This hostility extended to verbal abuse, assaults, and vandalism.

- Surveillance and Profiling: Government agencies significantly expanded surveillance of Muslim communities, with mosques and Muslim charities under constant monitoring. Many Muslims also reported feeling intimidated about speaking out on political issues.

- Psychological Impact: The widespread fear, harassment, and government scrutiny resulted in stress, fear of deportation, and alienation within Muslim and Arab communities. For many, this led to cultural trauma and identity crises.

Forced Migration and Displacement From War

The “War on Terror” launched after 9/11 drove new, large-scale displacements, primarily impacting Muslim-majority countries.

- Massive Displacement: The subsequent wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia, and other regions forcibly displaced at least 37 million people, either within their own countries or across international borders.

- Refugee Flows: Millions of people fled to neighboring countries like Pakistan, Jordan, Turkey, and Iran. This created a new dimension to migration, driven not by choice but by the violence and instability resulting from post-9/11 conflicts.

- Heightened Scrutiny of Refugees: Even refugees escaping war-torn countries faced skepticism and heightened security checks in potential host nations, with rhetoric increasingly shifting from humanitarianism to security.

Internal Migration and Community Impact

Fear and discrimination in the U.S. and Europe following 9/11 caused a different kind of migration: internal relocation away from concentrated communities.

- Shifting Demographics: In some neighborhoods with large Arab and South Asian populations, such as Coney Island Avenue in Brooklyn, post-9/11 crackdowns and fear of deportation caused many families to leave, fundamentally changing local demographics.

- Community Breakdown: The surveillance and policing tactics used by law enforcement created tensions within communities and eroded trust, causing many to pull back from public life or activism.

- Identity Crisis: Many Muslim youth, in particular, struggled with their dual identities as both American and Muslim in a climate where the two were often portrayed as contradictory.

Terrorism Organizations and Their Impact

Islamist Groups

A new wave or terrorism also manifested itself throughout the first quarter of 2025 and beyond. Terrorist organizations took root in Southeast Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. The threat from Islamist groups has evolved, with some historical networks declining while new factions influenced by ISIS have emerged.

Southeast Asia

Numerous terrorist and militant groups operate throughout Southeast Asia, with significant activity concentrated in the Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand, and Myanmar.

Groups range from Islamist extremists aligned with ISIS and al-Qaeda to domestic ethno-nationalist and separatist movements.

Key terrorist organizations operating in Southeast Asia include affiliates of the Islamic State (ISIS), the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG), remnants of Jemaah Islamiyah (JI). The southern Philippines is a major area of operation for many of these groups.

- ISIS–East Asia (ISIS-EA): This branch of ISIS is primarily based in the southern Philippines and aspires to create a caliphate in Southeast Asia. It conducts attacks against Philippine security forces and Christian civilians using IEDs and small arms. ISIS-EA includes veterans from older groups like Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) and Jemaah Islamiyah (JI).

- Operating Area: Predominantly in the southern Philippines, including the Sulu archipelago, though it aspires to expand throughout Southeast Asia.

- Affiliations: Officially recognized by ISIS in 2016, it incorporates veterans and members from older local militant groups, such as ASG and JI.

- Tactics: Uses improvised explosive devices (IEDs), vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices (VBIEDs), and small arms attacks against military, police, and Christian civilian targets.

- Leadership: Its leadership has been significantly weakened due to successful counter-terrorism operations by the Philippine government, but it remains a deadly threat.

- Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG): Operating primarily in the southern Philippines, ASG is a violent Islamist separatist group that historically had ties to al-Qaeda and Jemaah Islamiyah. Since a faction pledged allegiance to ISIS in 2014, its activities have included kidnappings for ransom, bombings, and assassinations.

- Operating Area: Basilan, Jolo, and Tawi-Tawi islands in the southern Philippines, as well as adjacent waters.

- Affiliations: Has historical links to al-Qaeda. A faction pledged allegiance to ISIS in 2014 and participated in the 2017 Marawi siege.

- Tactics: Known for kidnappings for ransom, bombings, assassinations, and extortion.

- Jemaah Islamiyah (JI): This transnational organization once aimed to establish an Islamic state across Southeast Asia and was responsible for the 2002 Bali bombings. Although senior leaders announced the group’s dissolution in June 2024, its extensive social and school networks remain, and some worry about the potential for splinter groups.

- Operating Area: Indonesia, with historical presence and connections in Malaysia, Singapore, and the southern Philippines.

- Current Status: In June 2024, JI’s senior leaders announced the group’s dissolution. However, the community and its extensive network of religious schools remain intact, and some analysts are concerned about the potential for splinter groups or a future return to violence.

- Influence: Historically linked to al-Qaeda, JI was responsible for large-scale attacks in the early 2000s, including the 2002 Bali bombings. It has also used its network of schools and charities for recruitment and funding.

Other Groups

- Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF): A splinter group that emerged from the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), a former rebel group in the Philippines. Factions of BIFF have pledged allegiance to ISIS.

- Maute Group (Dawlah Islamiyah-Lanao): An ISIS-affiliated group that, along with Isnilon Hapilon’s faction of ASG, was responsible for the 2017 Marawi siege. The group has been degraded but its remnants pose a continuing threat.

- Jemaah Ansharut Daulah (JAD): An ISIS-affiliated network in Indonesia that carried out several attacks before being weakened by counter-terrorism efforts.

- East Indonesia Mujahideen (MIT): An ISIS-affiliated group that has been significantly degraded by Indonesian security forces.

- Barisan Revolusi Nasional (BRN): This insurgent group is the most active and dominant in southern Thailand. Composed of hardline Salafists, its immediate goal is to make the region ungovernable through targeted assassinations, bombings, and guerrilla tactics.

- Jemaah Ansharut Daulah (JAD): A pro-ISIS network in Indonesia, JAD has seen its operational capacity decline significantly due to law enforcement pressure. It is responsible for past attacks against police and symbols of state authority.

- Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA): Active in Myanmar, this group has been designated a terrorist organization by the government. It has launched attacks against security posts and has killed security personnel and civilians.

Africa

Several of the world’s most dangerous terrorist organizations are active in Africa, particularly in the Sahel area (a vast semiarid region of North Africa to the south of the Sahara) area and East Africa.

These groups often exploit poor economic conditions, weak governance, and long-standing conflicts to gain influence and launch attacks.

Key Terrorist Organizations In Africa

The Sahel Region

- Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM): This al-Qaeda affiliate is a prominent and growing threat in the Sahel. It operates primarily in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger and uses porous borders to evade counterterrorism forces. The group is known for its ability to embed itself within local communities, exploiting weak governance to solidify its position.

- Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS): Operating in the Liptako-Gourma border region of Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger, ISGS is a splinter group of the Islamic State. It has escalated its violence against both military and civilian targets, and competes for resources and territory with JNIM.

- Boko Haram: This group is based in northeastern Nigeria but also active in neighboring Cameroon, Chad, and Niger in the Lake Chad Basin. It aims to establish an Islamist state and has been responsible for mass killings, bombings, and the mass kidnapping of schoolchildren. Though it has lost territory to its rival, Islamic State—West Africa Province (ISWAP), it remains a threat.

- Islamic State — West Africa Province (ISWAP): Emerging from a 2016 split within Boko Haram, ISWAP has become a major force in the Lake Chad region. It seeks to establish an Islamic State caliphate and exacerbates sectarian violence to attract new members.

East Africa

- Al-Shabaab: A formidable al-Qaeda affiliate based in Somalia, Al-Shabaab has proven resilient against numerous counterinsurgency campaigns. It exploits the Somali government’s limited capacity and dire humanitarian crises to conduct attacks in Somalia, Kenya, and Ethiopia. Its goals include overthrowing Somalia’s government and establishing a “Greater Somalia” under strict Islamic rule.

- Allied Democratic Forces (ADF): This group is active in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and has continued to unleash horrific violence.

- Ahlu Sunna Wal Jama’a: Also known as al-Shabaab in Mozambique, this group continues to carry out violent acts.

- Islamic State in Somalia (ISS): An expansionist group that has conducted its own campaign in Somalia, competing with Al-Shabaab.

North Africa

- Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM): An al-Qaeda affiliate, AQIM and its offshoots pose a threat in North Africa and have expanded their presence into the Sahel.

- Islamic State in Libya (ISIL-Libya) and Islamic State Sinai Province (ISIL-Sinai):These groups are affiliates of the Islamic State (ISIL/Daesh) and pose continued security challenges in North Africa.

Factors Contributing to Terrorism in Africa

- Weak Governance: Many governments lack the resources and capacity to control vast territories, leaving a vacuum that terrorist groups exploit.

- Socioeconomic Conditions: Poverty, lack of opportunity, and corruption are key drivers for recruitment. Terrorist groups can offer incentives to marginalized populations who feel neglected by the state.

- Intercommunal Tensions: Groups like ISGS and JNIM have leveraged local disputes and conflicts over resources to inflame tensions and recruit new members.

- Lack of Accountability: Ineffective justice systems and human rights abuses by government forces can fuel hostilities and push disenfranchised populations toward insurgent groups.

- Porous Borders: Terrorist organizations exploit poorly controlled borders to move fighters, weapons, and resources across countries.

The Middle East

Key Terrorist Organizations in the Middle East

- Islamic State (ISIS/ISIL): A splinter group of al-Qaeda that grew out of the conflict in Iraq and Syria, seeking to establish a caliphate and carrying out attacks using various methods.

- Al-Qaeda (AQ): A global terrorist network that has spawned various regional affiliates, including Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) in Yemen and Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) in North Africa.

- Hamas: An Iranian-backed Palestinian Islamist terrorist organization known for its attacks against Israel and its network of affiliates.

- Hezbollah: Another Iranian-backed group operating in Lebanon and Syria, with capabilities to conduct operations internationally and posing a threat to Israel and regional stability.

- Taliban: A group with origins in Afghanistan, which has been supported by Iran and has engaged in conflict in the region.

Motivations and Tactics

- Ideological Goals: Many of these groups are driven by radical Islamist ideologies, seeking to establish their interpretation of sharia law and expand their influence.

- Exploiting Instability: They capitalize on ongoing regional conflicts, political instability, and sectarian tensions to recruit members and gain resources.

- Violent Methods: Their tactics range from conventional attacks and bombings to suicide operations, kidnappings, and the use of advanced weaponry like precision-guided missiles.

External Support and Connections

- State Sponsorship: Groups like Hamas and Hezbollah receive significant financial and logistical backing from Iran, which enhances their capabilities and reach.

- Affiliate Networks: Al-Qaeda and ISIS have established affiliate networks across the Middle East and North Africa, further expanding their operational scope.

The Muslim Brotherhood

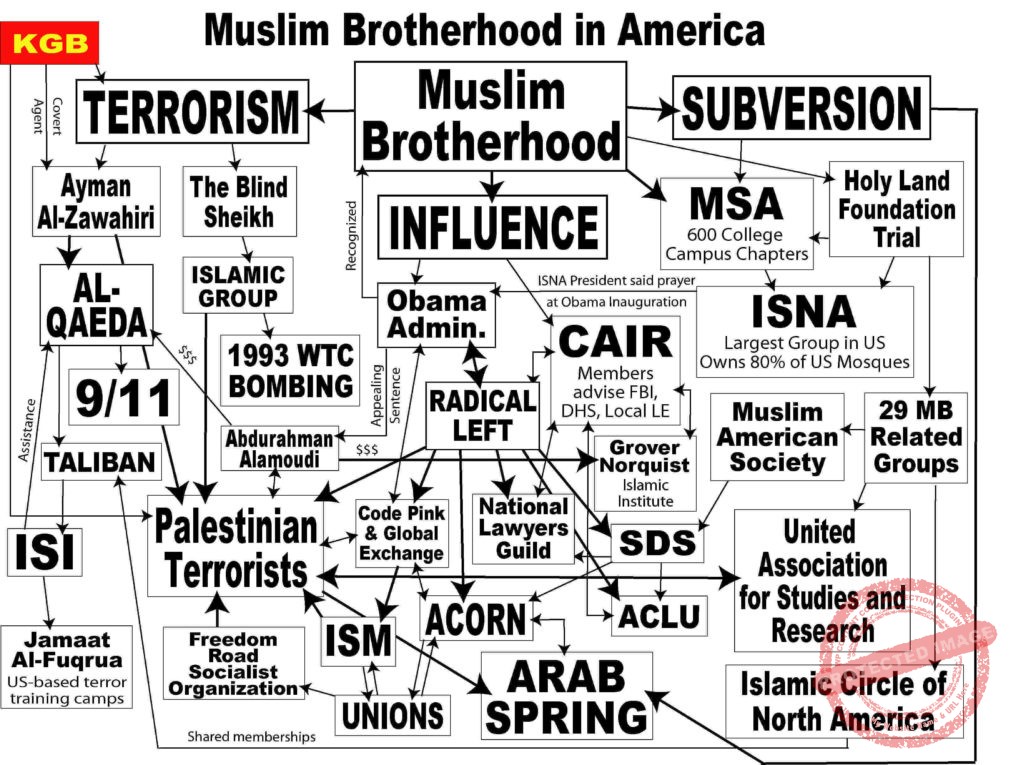

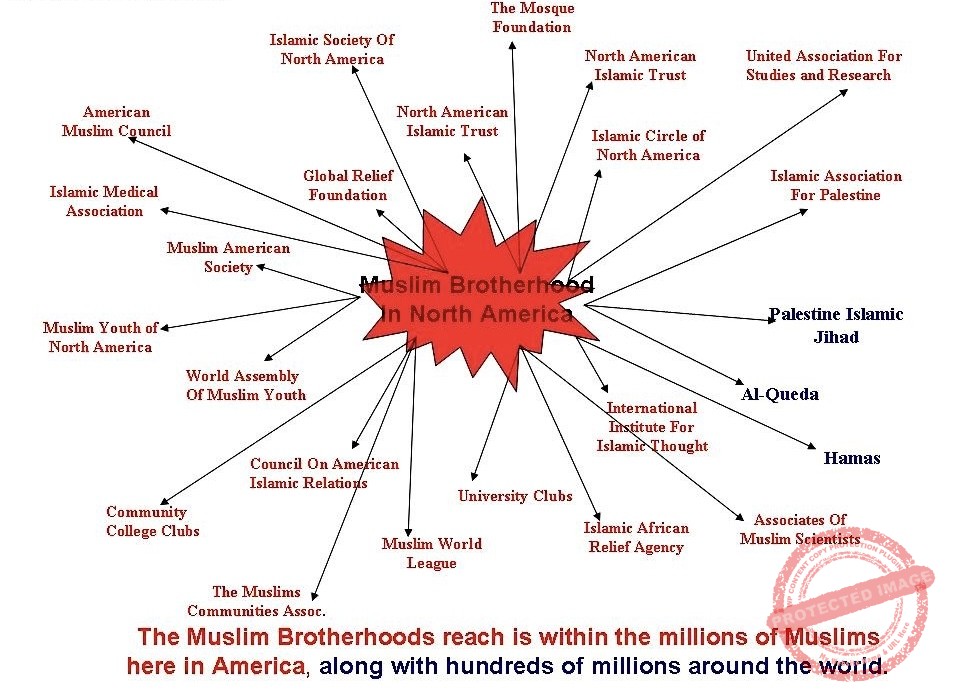

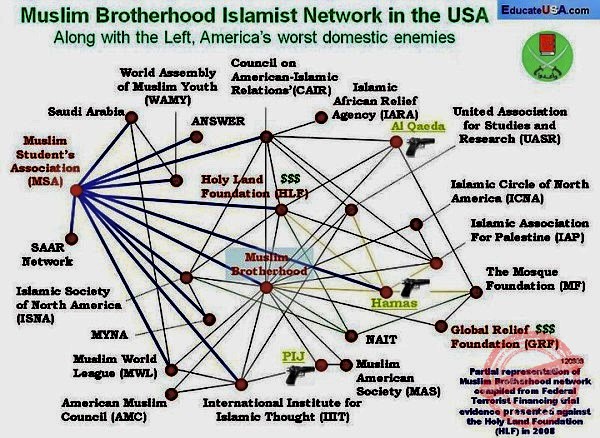

There are over 100 entirely different Islamic organizations throughout the United States ……… many of them operate with local and state offices, making it nearly impossible to trace down just how many groups there are. They all have one thing in common, though: each one received assistance in one form or another, from the Muslim Brotherhood.

The Muslim Brotherhood (MB) is a transnational Sunni Islamist organization founded in Egypt in 1928 that is currently in a state of deep crisis. Banned and suppressed in many Arab countries, its original base in Egypt has been largely decimated, and it now faces significant internal division and declining relevance.

Current Status

- Destruction of Egyptian Base: The group’s stronghold in Egypt was essentially destroyed after the 2013 military coup that ousted former president Mohamed Morsi, a Brotherhood member. In the ensuing years, many of the group’s leaders have been imprisoned or killed, and the Egyptian government has declared the Brotherhood a terrorist organization.

- Dissolution in Jordan: In April 2025, Jordan’s Interior Minister announced an immediate ban on the Muslim Brotherhood and ordered the confiscation of its assets and offices. This followed the arrest of 16 members accused of plotting attacks and seeking to destabilize the country.

- Leadership struggle: The movement has been plagued by internal divisions since 2013, with different factions vying for control and clashing over strategy. Muhyeddine al-Zayet was elected as acting leader in March 2023, following the death of his predecessor, but the organization remains fractured.

- Struggles in Exile: While some leaders and members have regrouped in countries like Qatar and Turkey, the movement’s capabilities have declined. It struggles to influence policy, raise funds, and mobilize supporters. The hostile regional environment has further weakened its position.

- Ongoing Legal Pressure: The Muslim Brotherhood has been designated as a terrorist organization by Bahrain, Egypt, Russia, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Jordan. In July 2025, a bipartisan bill was introduced in the U.S. Congress to designate the global organization as a terrorist group, though the U.S. has already designated some branches, members, and affiliates.

Ideological Roots

- Founder: The Muslim Brotherhood was founded in 1928 by Hassan al-Banna. It initially started as a pan-Islamic, religious, and social movement that promoted the principles of Islam, provided social services, and advocated for an end to British colonial rule.

- Slogan: Its most famous slogan is “Islam is the solution,” reflecting its goal of establishing a state ruled by sharia law under a caliphate.

- Offshoots and Ideology: The Brotherhood’s ideas have influenced numerous Islamist movements, including the Palestinian group Hamas, which is an official offshoot. The writings of ideologues like Sayyid Qutb, who advocated for the use of violence to achieve an Islamic society, have also influenced many jihadist movements.

Shifting Strategies and Accusations

- Early Violence: While the group claims it renounced violence decades ago, it did have an armed wing known as the “Secret Apparatus” that was involved in bombings and assassinations in the 1940s.

- “Grand Jihad”: According to a 1991 internal document, the group’s strategic goal in North America involved “Civilization Jihadist responsibility” to destroy “Western civilization from within”.

- Secretive Tactics: The Brotherhood and its affiliated organizations have a history of secrecy and deception to further their goals. They have been accused of presenting a moderate public image while holding more radical ideological aims.

- Hamas Connections: Documents revealed during the 2008 trial of the Holy Land Foundation proved that the Muslim Brotherhood created a U.S. network to raise money for its Palestinian offshoot, Hamas.

For all of its history, the fact that it’s banned in many Islamic countries, for its rhetoric and hands-on with the creation of all of the Islamic organizations in the United States … …… the Muslim Brotherhood still has not been declared a terrorist organization by America.

The Globalization Of Islam

905 – 001 – I

http://discerningislam.com

Last Updated: 05/2022

See COPYRIGHT information below.