The Lesser Crusades

13th Century

Pope Innocent III also began preaching what became the Fourth Crusade in 1200, primarily in France but also in England and Germany. After gathering in Venice, the Crusade was used by Doge Enrico Dandolo and Philip of Swabia to further their secular ambitions. Dandolo aimed to expand Venice’s power in the Eastern Mediterranean, and Philip intended to restore his exiled nephew, Alexios IV Angelos, along with Angelos’s father, Isaac II Angelos, to the throne of Byzantium. This would require overthrowing the present ruler, Alexios III Angelos, the uncle of Alexios IV. When an insufficient number of knights arrived in Venice, the Crusaders were unable to pay the Venetians for a fleet, so they agreed to divert to Constantinople and share what could be looted as payment. As collateral, the Crusaders seized the Christian city of Zara; Innocent was appalled, and promptly excommunicated them. However, the French Crusaders eventually had their excommunications lifted. When the original purpose of the campaign was defeated by the assassination of Alexios IV Angelos, they conquered Constantinople, not once but twice. Following upon their initial success, the Crusaders captured Constantinople again and this time sacked it, pillaging churches and killing many citizens. The

Fourth Crusade never came within 1,000 miles of its objective of Jerusalem.

The 13th century saw popular outbursts of ecstatic piety in support of the Crusades such as that resulting in the Children’s Crusade in 1212. Large groups of young adults and children spontaneously gathered, believing their innocence would enable success where their elders had failed. Few, if any at all, journeyed to the Eastern Mediterranean. Although little reliable evidence survives for these events, they provide an indication of how hearts and minds could be engaged for the cause.

Following Innocent III’s Fourth Council of the Lateran, crusading resumed in 1217 against Saladin’s Ayyubid successors in Egypt and Syria for what is classified as the Fifth Crusade. Led by Andrew II of Hungary and Leopold VI, Duke of Austria, forces drawn mainly from Hungary, Germany, Flanders, and Frisia achieved little. Leopold and John of Brienne besieged and captured Damietta but an army advancing into Egypt was compelled to surrender. Damietta was returned and an eight-year truce followed. Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, was excommunicated for breaking a treaty obligation.

The Pope had required him to lead a crusade. However, since his marriage to Isabella II of Jerusalem gave him a claim to the kingdom of Jerusalem, he finally arrived at Acre in 1228. Frederick was culturally the Christian monarch most empathetic to the Muslim world, having grown up in Sicily, with a Muslim bodyguard and even a harem. His great diplomatic skills meant that the Sixth Crusade was largely negotiation supported by force. A peace treaty was agreed upon, giving Latin Christians most of Jerusalem and a strip of territory that linked the city to Acre, while the Muslims controlled their sacred areas. In return, an alliance was made with Al-Kamil, Sultan of Egypt, against all of his enemies of whatever religion. The treaty and suspicions about Frederick’s ambitions in the region made him unpopular, and he was forced to return to his domains when they were attacked by Pope Gregory IX. While the Holy Roman Empire and the Papacy were in conflict, it often fell to secular leaders to campaign. What is sometimes known as the Barons’ Crusade was led by Theobald I of Navarre and Richard of Cornwall; it combined forceful diplomacy and the playing of rival Ayyubid factions off against each other. This brief renaissance for Frankish Jerusalem was illusory, being dependent on Ayyubid weakness and division following the death of Al-Kamil.

In 1244 a band of Khwarezmian mercenaries travelling to Egypt to serve As-Salih Ismail, Emir of Damascus, seemingly of their own volition, captured Jerusalem en route and defeated a combined Christian and Syrian army at the Battle of La Forbie. In response, Louis IX, king of France, organized a Crusade, called the Seventh Crusade, to attack Egypt, arriving in 1249. It was not a success. Louis was defeated at Mansura and captured as he retreated to Damietta. Another truce was agreed upon for a ten-year period, and Louis was ransomed. Louis remained in Syria until 1254 to consolidate the Crusader states. From 1265 to 1271, the Mamluk sultan Baibars drove the Franks to a few small coastal outposts.

Late 13th century politics in the Eastern Mediterranean were complex, with a number of powerful interested parties. Baibars had three key objectives: to prevent an alliance between the Latins and the Mongols, to cause dissension between the Mongols particularly between the Golden Horde and the Persian Ilkhanate, and to maintain access to a supply of slave recruits from the Russian steppes. In this he developed diplomatic ties with Manfred, King of Sicily, supporting him against the Papacy and Louis IX’s brother Charles of Anjou. The Crusader states were fragmented, and various powers were competing for influence. In the War of Saint Sabas, Venice drove the Genoese from Acre to Tyre where they continued to trade happily with Baibars’ Egypt. Indeed, Baibars negotiated free passage for the Genoese with Michael VIII Palaiologos, Emperor of Nicaea, the newly restored ruler of Constantinople.

The French, led by Charles, similarly sought to expand their influence; Charles seized Sicily and Byzantine territory while marrying his daughters to the Latin claimants to Byzantium. To create his own claim to the throne of Jerusalem, Charles executed one rival and purchased the rights to the city from another. In 1270 Charles turned his brother King Louis IX’s last Crusade, known as the Eighth Crusade, to his own advantage by persuading Louis to attack his rebel Arab vassals in Tunis. Louis’ army was devastated by disease, and Louis himself died at Tunis on 25 August. Louis’ fleet returned to France, leaving only Prince Edward, the future king of England, and a small retinue to continue what is known as the Ninth Crusade. Edward survived an assassination attempt organized by Baibars, negotiated a ten-year truce, and then returned to manage his affairs in England. This ended the last significant crusading effort in the Eastern Mediterranean. The 1281 election of a French pope, Martin IV, brought the full power of the papacy into line behind Charles. He prepared to launch a crusade against Constantinople but, in what became known as the Sicilian Vespers, an uprising fomented by Michael VIII Palaiologos deprived him of the resources of Sicily, and Peter III of Aragon was proclaimed king of Sicily. In response, Martin excommunicated Peter and called for an Aragonese Crusade, which was unsuccessful. In 1285 Charles died, having spent his life trying to amass a Mediterranean empire; he and Louis had viewed themselves as God’s instruments to uphold the papacy.

The causes of the decline in Crusading and the failure of the Crusader States is multi-faceted. Historians have attempted to explain this in terms of Muslim reunification and Jihadi enthusiasm but Thomas Asbridge, amongst others, considers this too simplistic. Muslim unity was sporadic and the desire for Jihad ephemeral. The nature of Crusades was unsuited to the conquest and defense of the Holy Land. Crusaders were on a personal pilgrimage and usually returned when it was completed. Although the philosophy of Crusading changed over time, the Crusades continued to provide short-lived armies without centralized leadership led by independently minded potentates. What the Crusader states needed were large standing armies. Religious fervor enabled amazing feats of military endeavor but proved difficult to direct and control. Succession disputes and dynastic rivalries in Europe, failed harvests and heretical outbreaks, all contributed to reducing Latin Europe’s concerns for Jerusalem. Ultimately, even though the fighting was also at the edge of the Islamic world, the huge distances made the mounting of Crusades and the maintenance of communications insurmountably difficult. It enabled Islam, under the charismatic leadership of Nur al-Din and Saladin as well as the ruthless Baibars to use the logistical advantages from proximity to victorious effect. The mainland Crusader states of the outremer were finally extinguished with the fall of Tripoli in 1289 and Acre in 1291. Many Latin Christians were evacuated to Cyprus by boat, were killed or enslaved.

European Campaigns

Northern Crusades

Extent Of The Teutonic Order In 1300

The success of the First Crusade inspired 12th century popes such as Celestine III, Innocent III, Honorius III, and Gregory IX to call for military campaigns with the aim of Christianizing the more remote regions of northern and north-eastern Europe. These campaigns are known as the Northern Crusades. The Wendish Crusade of 1147 saw Saxons, Danes, and Poles attempt to forcibly convert the tribes of Mecklenburg and Lusatia, who were Polabian Slavs or “Wends.” Celestine III called for a Crusade in 1193, but when Bishop Berthold of Hanover responded in 1198, he led a large army into defeat and to his death. In response, Innocent III issued a bull declaring a Crusade, and Hartwig of Uthlede, Bishop of Bremen, along with the Brothers of the Sword brought all of the north-east Baltic under Catholic control. Konrad of Masovia gave Chelmno to the Teutonic Knights in 1226 as a base for a Crusade against the local Polish princes. The Livonian Brothers of the Sword were defeated by the Lithuanians, so in 1237 Gregory IX merged the remainder of the order into the Teutonic Order as the Livonian Order. By the middle of the century, the Teutonic Knights completed their conquest of the Prussians before conquering and converting the Lithuanians in the subsequent decades. The order also came into conflict with the Eastern Orthodox Church of the Pskov and Novgorod Republics. In 1240 the Orthodox Novgorod army defeated the Catholic Swedes in the Battle of the Neva, and, two years later, they defeated the Livonian Order in the Battle on the Ice.

Albigensian Crusade

The Albigensian Crusade (1209–1229) was a campaign against heretics that Innocent III launched to eradicate Catharism, which had gained a substantial following in southern France. The Cathars were brutally suppressed and the autonomous County of Toulouse formally submitted to the crown of France. The county’s sole heiress Joan was engaged to Alphonse, Count of Poitiers, a younger brother of Louis IX of France. The marriage was childless so that after Joan’s death the county fell under the direct control of Capetian France which was in part one of the motivations of the Crusaders.

Bosnian Crusade

The Bosnian Crusade was a campaign against the independent Bosnian Church, which was accused of Catharism (Bogomilism). However, it was also possibly motivated by Hungarian territorial ambitions. In 1216 a mission was sent to convert Bosnia to Rome but failed. In 1225 Honorius III encouraged the Hungarians to crusade in Bosnia. This ended in failure after the Hungarians were defeated by the Mongols at the Battle of Mohi. From 1234 Gregory IX encouraged further crusading, but again the Bosniaks repelled the Hungarians.

Reconquista

In the Iberian peninsula, Crusader privileges were given to those aiding the Templars, the Hospitallers, and the Iberian orders that merged with the orders of Calatrava and Santiago. The Christian kingdoms pushed the Muslim Moors and Almohads back in frequent Papal-endorsed Iberian Crusades from 1212 to 1265. The Emirate of Granada held out until 1492, at which point the Muslims and Jews were finally expelled from the peninsula.

Late Middle Ages and Renaissance

Minor Crusading efforts lingered into the 14th century, and several Crusades were launched during the 14th and 15th centuries to counter the expansion of the Ottoman conquest of the Balkans. In 1309 as many as 30,000 peasants gathered from England, north-eastern France, and Germany proceeded as far as Avignon but disbanded there.

Peter I of Cyprus captured and sacked Alexandria in 1365 in what became known as the Alexandrian Crusade; his motivation was as much commercial as religious. Louis II led the 1390 Barbary Crusade against Muslim pirates in North Africa; after a ten-week siege, the Crusaders signed a ten-year truce.

The Ottomans had conquered most of the Balkans and reduced Byzantine influence to the area immediately surrounding Constantinople after victory at the Battle of Kosovo in 1389. Nicopolis was seized from the Bulgarian Tsar Ivan Shishman in 1393 and a year later Pope Boniface IX proclaimed a new Crusade against the Turks, although the Western Schism had split the papacy. This Crusade was led by Sigismund of Luxembourg, King of Hungary; many French nobles joined Sigismund’s forces, including the Crusade’s military leader, John the Fearless (son of the Duke of Burgundy). Sigismund advised the Crusaders to adopt a cautious, more defensive strategy, when they reached the Danube, instead they besieged the city of Nicopolis. The Ottomans defeated them in the Battle of Nicopolis on 25 September, capturing 3,000 prisoners.

The Hussite Wars, also known as the Hussite Crusade, involved military action against the Bohemian Reformation in the Kingdom of Bohemia and the followers of early Czech church reformer Jan Hus, who was burned at the stake in 1415. Crusades were declared five times during that period: in 1420, 1421, 1422, 1427, and 1431. These expeditions forced the Hussite forces, who disagreed on many doctrinal points, to unite to drive out the invaders. The wars ended in 1436 with the ratification of the compromise Compacts of Basel by the Church and the Hussites.

As the Ottomans pressed westward, Sultan Murad II destroyed the last Papal-funded Crusade at Varna on the Black Sea in 1444 and four years later crushed the last Hungarian expedition. In 1453 they extinguished most of the remains of the Byzantine Empire with the capture of Constantinople. John Hunyadi and Giovanni da Capistrano organized a 1456 Crusade to oppose the Ottoman Empire and lift its Siege of Belgrade. Æneas Sylvius and John of Capistrano preached the Crusade, the princes of the Holy Roman Empire in the Diets of Ratisbon and Frankfurt promised assistance, and a league was formed between Venice, Florence, and Milan, but nothing eventually came of it. In April 1487 Pope Innocent VIII called for a Crusade against the Waldensians of Savoy, the Piedmont, and the Dauphiné in southern France and northern Italy because they were unorthodox and heretical. The only efforts undertaken were in the Dauphiné, resulting in little change. Venice was the only polity to continue to pose a significant threat to the Ottomans in the Mediterranean, but it pursued the “Crusade” mostly for its commercial interests, leading to the protracted Ottoman–Venetian Wars, which continued, with interruptions, until 1718. The end of the Crusading in terms of at least nominal efforts by Catholic Europe against Muslim incursion, came in the 16th century, when the Franco-Imperial wars assumed continental proportions. Francis I of France sought allies from all quarters, including from German Protestant princes and Muslims. Amongst these, he entered into one of the capitulations of the Ottoman Empire with Suleiman the Magnificent while making common cause with Hayreddin Barbarossa and a number of the Sultan’s North African vassals.

Crusader States

After the First Crusade’s capture of Jerusalem and victory at Ascalon the majority of the Crusaders considered their personal pilgrimage complete and returned to Europe. Godfrey found himself left with only

300 knights and 2,000 infantry to defend the territory won in the Eastern Mediterranean. Of the crusader princes, only Tancred remained with the aim of establishing his own lordship. At this point the Franks held Jerusalem and two great Syrian cities – Antioch and Edessa – but not the surrounding country. Jerusalem remained economically sterile despite the advantages of being the centre of administration of church and state and benefiting from streams of pilgrims.

The “Law of Conquest” supported the seizure of land and property by impecunious Crusaders from the autochthonous population, enabling poor men to become rich and part of a noble class. Although some historians, like Jotischky, question the model once proposed, in which the primary motivation was understood in sociological and economic rather than spiritual terms.

That class did not expel the native population, but adopted strict segregation and at no point attempted to integrate it by way of religious conversion. In this way the Crusaders created a colonial noble class that perpetuated itself through an incessant flow of religious pilgrims and settlers keen to take economic advantage. The territorial gains followed distinct ethnic and linguistic entities. The Principality of Antioch, founded in 1098 and ruled by Bohemond, became Norman in character and custom. The Kingdom of Jerusalem, founded in 1099, followed the traditions of northern France. The County of Tripoli, founded in 1104 (although the city of Tripoli itself remained in Muslim control until 1109) by Raymond de Saint-Gilles became Provençal. The County of Edessa, founded in 1098, differed in that although it was ruled by the French Bouillons and Courteneys its largely Armenian and Jacobite native nobility was preserved. These states were the first examples of “Europe overseas.” They are generally known by historians as Outremer, from the French outre-mer (“overseas” in English).

Largely based in the ports of Acre and Tyre, Italian, Provençal and Spanish communes provided a significant characteristic of Crusader social stratification and political organisation. Separate from the Frankish nobles or burgesses, the communes were autonomous political entities closely linked to their countries of origin. This gave the inhabitants the ability to monopolize foreign trade and almost all banking and shipping in the Crusader states. Every opportunity to extend trade privileges was taken. One example saw the Venetian Doge receiving one third of Tyre, its territories and exemption from all taxes, after Venice participated in the successful 1124 siege of the city. However, despite all efforts, the two ports were unable to replace Alexandria and Constantinople as the primary centres of commerce in the region. Instead, the communes competed with the Crown and each other to maintain economic advantage. Power derived from the support of the communards’ native cities rather than their number, which never reached more than several hundred. Thus by the middle of the 13th century, the rulers of the communes were barely required to recognize the authority of the crusaders and divided Acre into a number of fortified miniature republics.

The Fourth Crusade established a Latin Empire in the east and allowed participating crusaders to partition the Byzantine European territory. The Latin emperor controlled one-fourth of the Byzantine territory, Venice three-eighths (including three-eighths of the city of Constantinople), and the remainder was divided among the other leaders of the Crusade. This began the period of Greek history known as Frankokratia or Latinokratia (“Frankish [or Latin] rule”), when Catholic Western European nobles – primarily from France and Italy – established states on former Byzantine territory and ruled over the Orthodox Byzantine Greeks. In the long run, the sole beneficiary was Venice.

Military Orders

The Crusaders’ mentality to imitate the customs from their Western European homelands meant that there were very few innovations developed from the culture of the crusader states. Three notable exceptions to this rule are the military orders, warfare and fortifications. The Hospitallers (Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem) were founded in Jerusalem before the First Crusade but added a martial element to its ongoing medical functions to become a much larger military order. In this way the knighthood entered the previously monastic and ecclesiastical sphere.

The military orders such as the Knights Hospitaller and the Knights Templar provided Latin Christendom’s first professional armies in support of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem and the other Crusader states. The Poor Knights of Christ (Templars) and their Temple of Solomon were founded around 1119 by a small band of knights who dedicated themselves to protecting pilgrims en route to Jerusalem. The Hospitallers and the Templars became supranational organisations as Papal support led to rich donations of land and revenue across Europe. This in turn led to a steady flow of new recruits and the wealth to maintain multiple fortifications across the Outremer. In time, this developed into autonomous power in the region. After the fall of Acre the Hospitallers first relocated to Cyprus, then conquered and ruled Rhodes (1309–1522) and Malta (1530–1798), and continue in existence to the present day. Philip IV of France probably had financial and political reasons to oppose the Knights Templar, which led to him exerting pressure on Pope Clement V. The Pope responded in 1312, with a series of papal bulls including Vox in excelso and Ad providam that dissolved the order on the alleged and probably false grounds of sodomy, magic, and heresy.

Legacy

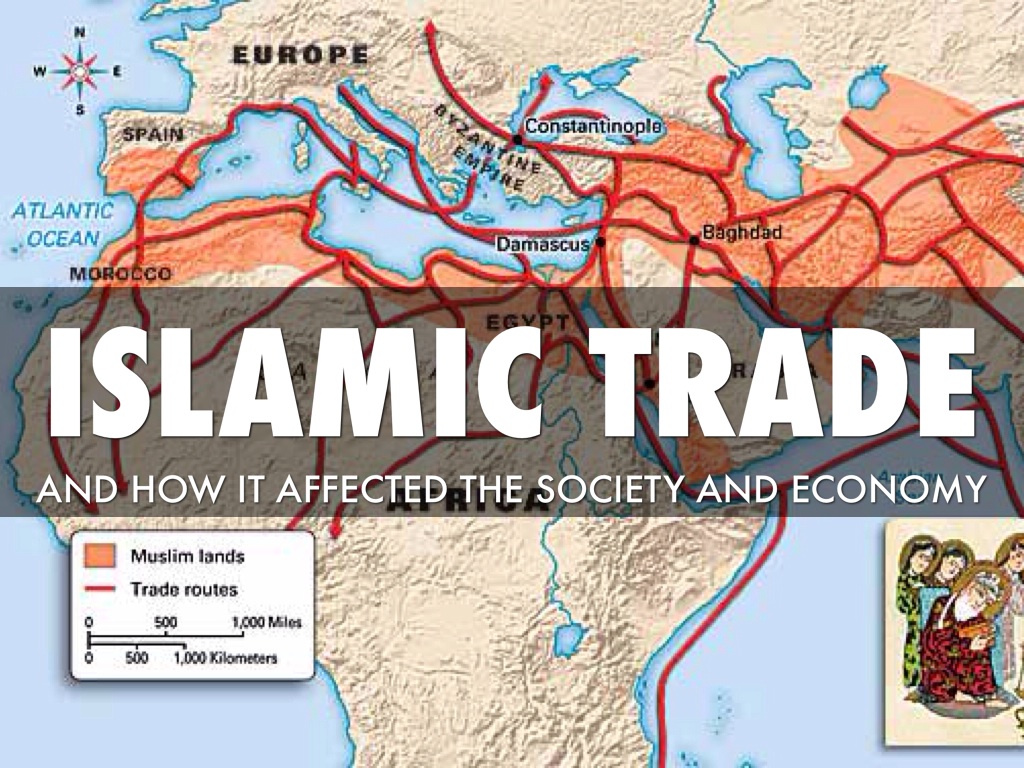

The Kingdom of Jerusalem was the first experiment in European colonialism creating a ‘Europe Overseas’ or Outremer. The Arabs had come to dominate trade in the Mediterranean after their conquests. Before the Crusades, Fatimids had trade relations with Italian city-states like Amalfi and Genoa. Amalfian merchants are attested to have lived in Cairo in 10th century by Cairo Geniza documents and were allowed to live in Jerusalem around 1060 by al-Mustansir. In return for assisting the Crusaders, Genoa, Pisa and Venice were granted wide privileges in matter of land, trade and jurisdiction. Amalfi however didn’t participate. The raising, transportation, and supply of large armies led to flourishing trade between Europe and the outremer. The Italian city states of Genoa and Venice flourished, creating profitable trading colonies in the Eastern Mediterranean. The colonies allowed them to engage in trade with eastern markets. This trade was sustained through the middle Byzantine and Ottoman eras, and the communities were often assimilated and known as Levantines or Franco-Levantines.

The Crusades consolidated the papal leadership of the Latin Church, reinforcing the link between Western Christendom, feudalism, and militarism and increased the tolerance of the clergy to violence. The growth of the system of indulgences became a catalyst for the Protestant Reformation in the early 16th century. The Crusades also had a role in the creation and institutionalization of the military and the Dominican orders as well as the Medieval Inquisition.

The behavior of the Crusaders appalled the Greeks and Muslims, creating a lasting barrier between the Latin world and both the Islamic and Orthodox religions. It was an obstacle to the reunification of the Christian church and created a perception of Westerners as defeated aggressors.

Many historians argue that the interaction between the western Christian and Islamic cultures was a significant, ultimately positive, factor in the development of European civilization and the Renaissance. The many interactions between Europeans and the Islamic world across the entire length of the Mediterranean Sea led to improved perceptions of Islamic culture, but also make it difficult for historians to identify the specific source of various instances of cultural cross-fertilization. The art and architecture of the Outremer show clear evidence of cultural fusion but it is difficult to track illumination of manuscripts and castle design back to their sources. Textual sources are simpler, and translations made in Antioch are notable but considered secondary in importance to the works emanating from Muslim Spain and the hybrid culture of Sicily. In addition, Muslim libraries contained classical Greek and Roman texts that allowed Europe to rediscover pre-Christian philosophy, science and medicine.

Jonathan Riley-Smith considers that much of the popular understanding of the Crusades derives from the novels of Walter Scott and the French histories by Joseph François Michaud. The Crusades provided an enormous amount of source material, stories of heroism, and interest that underpinned growth in medieval literature, romance, and philosophy.

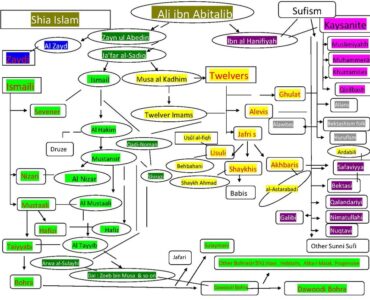

Historical parallelism and the tradition of drawing inspiration from the Middle Ages have become keystones of Islamic ideology. Secular Arab Nationalism concentrates on the idea of Western Imperialism. Gamal Abdel Nasser likened himself to Saladin and imperialism to the Crusades. In his History of the Crusades Sa’id Ashur emphasized the similarity between the modern and medieval situation facing Muslims and the need to study the Crusades in depth. Sayyid Qutb declared there was an international Crusader conspiracy. The ideas of Jihad and a long struggle have developed some currency.

Historiography

Five major sources of information exist on the Council of Clermont that led to the First Crusade: the anonymous Gesta Francorum (The Deeds of the Franks), dated about 1100–01; Fulcher of Chartres, who attended the council; Robert the Monk, who may have been present, and the absent Baldric, archbishop of Dol and Guibert de Nogent. These retrospective accounts differ greatly. In his 1106–07 Historia Iherosolimitana, Robert the Monk wrote that Urban asked western Roman Catholic Christians to aid the Orthodox Byzantine Empire because “Deus vult” (“God wills it”) and promised absolution to participants; according to other sources, the pope promised an indulgence. In these accounts, Urban emphasizes reconquering the Holy Land more than aiding the emperor, and lists gruesome offenses allegedly committed by Muslims. Urban wrote to those “waiting in Flanders” that the Turks, in addition to ravaging the “churches of God in the eastern regions,” seized “the Holy City of Christ, embellished by his passion and resurrection — and blasphemy to say it — have sold her and her churches into abominable slavery.” Although the pope did not explicitly call for the reconquest of Jerusalem, he called for military “liberation” of the Eastern Churches.

During the 16th century Reformation and Counter-Reformation, Western historians saw the Crusades through the lens of their own religious beliefs. Protestants saw them as a manifestation of the evils of the papacy, and Catholics viewed them as forces for good. Eighteenth-century Enlightenment historians tended to view the Middle Ages in general, and the Crusades in particular, as the efforts of barbarian cultures driven by fanaticism. These scholars expressed moral outrage at the conduct of the Crusaders and criticised the Crusades’ misdirection – that of the Fourth in particular, which attacked a Christian power (the Byzantine Empire) instead of Islam. The Fourth Crusade had resulted in the sacking of Constantinople, effectively ending any chance of reconciling the East–West Schism and leading to the fall of the Byzantine Empire to the Ottomans. In The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, 18th century English historian Edward Gibbon wrote that the Crusaders’ efforts could have been more profitably directed towards improving their own countries.

The 20th century produced three important histories of the Crusades: one by Steven Runciman, another by Rene Grousset, and a multi-author work edited by Kenneth Setton. Historians in this period often echoed Enlightenment-era criticism: Runciman wrote during the 1950s, “High ideals were besmirched by cruelty and greed . . . the Holy War was nothing more than a long act of intolerance in the name of God.” According to Norman Davies, the Crusades contradicted the Peace and Truce of God supported by Urban and reinforced the connection between Western Christendom, feudalism, and militarism. The formation of military religious orders scandalized the Orthodox Byzantines, and Crusaders pillaged countries they crossed on their journey east. Violating their oath to restore land to the Byzantines, they often kept the land for themselves. The Fourth Crusade is widely considered controversial in its “betrayal” of Byzantium. Similarly, Norman Housley viewed the persecution of Jews in the First Crusade – a pogrom in the Rhineland and the massacre of thousands of Jews in Central Europe – as part of the long history of anti-Semitism in Europe.

With an increasing focus on gender studies in the early 21st century, studies have examined the topic of “Women in the Crusades.” An essay collection on the topic was published in 2001 under the title Gendering the Crusades. In an essay on “Women Warriors,” Keren Caspi-Reisfeld concludes that “the most significant role played by women in the West was in maintaining the status quo,” in the sense of noble women acting as regents of feudal estates while their husbands were campaigning. The presence of individual noble women in Crusades has been noted, such as Eleanor of Aquitaine (who joined her husband, Louis VII). The presence of non-noble women in the Crusading armies, as in medieval warfare in general, was mostly in the role of logistic support (such as “washerwomen”), while the occasional presence of women soldiers was recorded by Muslim historians.The Muslim world exhibited little interest in European culture until the 16th century and in the Crusades until the mid-19th century. There was no history of the Crusades translated into Arabic until 1865 and no published work by a Muslim until 1899. In the late 19th century, Arabic-speaking Syrian Christians began translating French histories into Arabic, leading to the replacement of the term “wars of the Ifranj” – Franks – with al-hurub al Salabiyya – wars of the Cross. Namik Kamel published the first modern Saladin biography in 1872. The Jerusalem visit in 1898 of Kaiser Wilhelm prompted further interest, with Sayyid Ali al-Harri producing the first Arabic history of the Crusades. Muslim thinkers, politicians and historians have drawn parallels between the Crusades and modern political developments such as the French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon, Mandatory Palestine, and the United Nations mandated foundation of the state of Israel.

The Lesser Crusades: 13th Century

802 – 001

https://discerning-Islam.org

Last Updated: 01/2022

See COPYRIGHT information below.