Women At The Rise Of Islam

Women played a critical role in the early history of Islam. The Prophet Muḥammad was born in the city of Mecca in approximately 570 A.D. and began receiving revelations at the age of forty, in 610 A.D. He was extremely distressed by his first revelatory experience and feared he was going insane. In confusion and distress, he turned to his wife Khadīja. Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, second in authority only to the Qurʾān for the majority of Muslims, contains the description of how Khadīja comforted and counseled Muḥammad, eventually convincing him that his was a true calling from Allah. In doing so, she became the first person to accept the revelations received by Muḥammad and the first follower of Islam. Interestingly, the story itself is told on the authority of another important woman in early Islam — Muḥammad’s second wife, ʿĀʾishah. Through the revelation of the Qurʾān, Muḥammad instituted revolutionary changes affecting the status of women, prohibiting the common practices of female infanticide (16:58–59, 17:3) and unlawful inheriting of women (4:19), guaranteeing women a share of inheritance (4:7) and the right to their own earnings (4:32).

Khadīja, ʿĀʾishah, and Muḥammad’s other wives and female companions provide role models for Muslim women, and Muḥammad’s relationships with the women of his ahousehold and community serve as an ideal for Muslims. The picture painted by aḥādīth and biographical literature is one of dynamic, outspoken women who actively participated in the life of the community in Medina. Many of them transmitted the stories that still serve as the primary source of information on Muḥammad and the earliest community of Muslims.

After the death of Muḥammad, the Muslims rapidly defeated both the Persian and Byzantine Empires, conquering vast amounts of territory encompassing peoples of many different cultures. Over time, people from the conquered territories converted to Islam, bringing their existing understandings, assumptions, social customs, and traditions to emerging interpretations and institutions of the new faith. Social and cultural norms have had an impact on religious ideas and practices throughout Muslim history to the current day. This is why the status and situation of Muslim women varies from time to time and place to place.

Popular Images And Stereotypes Of Muslim Women

The non-Muslim world has long been fascinated with the status and role of women in Islam. Popular views in the imagination of many non-Muslims in Europe and North America have been bifurcated between the romanticized view of a decadent and indolent life in the mysterious “harem” and veiled, secluded, and silenced women, under the oppressive control of the men in their lives. Writing for a popular literary magazine, in 1902, columnist Mary Mills Patrick describes life in “the Harem” for a “domestic Turkish woman” as one of indolence and luxury.

“Who in America,” the author asks, “can enjoy the luxury of a bath that lasts all day, undisturbed by hurry or anxiety, or any thought of neglected duties?” (Patrick, 1902, p. 341).

Writing just a few years earlier, Stanley Lane-Poole paints a similar picture of the life of Egyptian women in his 1898 work, Cairo: Sketches of Its History, Monuments, and Social Life. In addition to food, gossip, and visits to the public bath, Lane-Poole adds stimulation “of their husbands’ affections” to the list of “simple pleasures” enjoyed by women living in “the harim.” These types of portrayals of Muslim women became fodder for Hollywood, which wove these images into the fabric of the popular imagination throughout the twentieth century, from silent films to Harum Scaram and I Dream of Jeannie to Princess Jasmine in Disney’s Aladdin. In the twentieth and early twenty-first century, the image of Islam has been forever altered by the Iranian revolution, the issue of veiling in Europe, and the tragic events of September 11, 2001. The image of the Muslim woman has borne the brunt of that change, perhaps because the veil is the most visible sign of Islam in the public sphere. Now, instead of the chiffon pantaloons and velvet bras of the harem, Muslim women are depicted swathed in all-enveloping black shrouds, faceless and voiceless creatures oppressed by their “evil” and “violent” religion. All of these stereotypes arise in the imaginations of outsiders looking at Muslim women from across a chasm of ignorance. The stereotypes thrive because most non-Muslims in Europe and North America lack the knowledge necessary to overcome them.

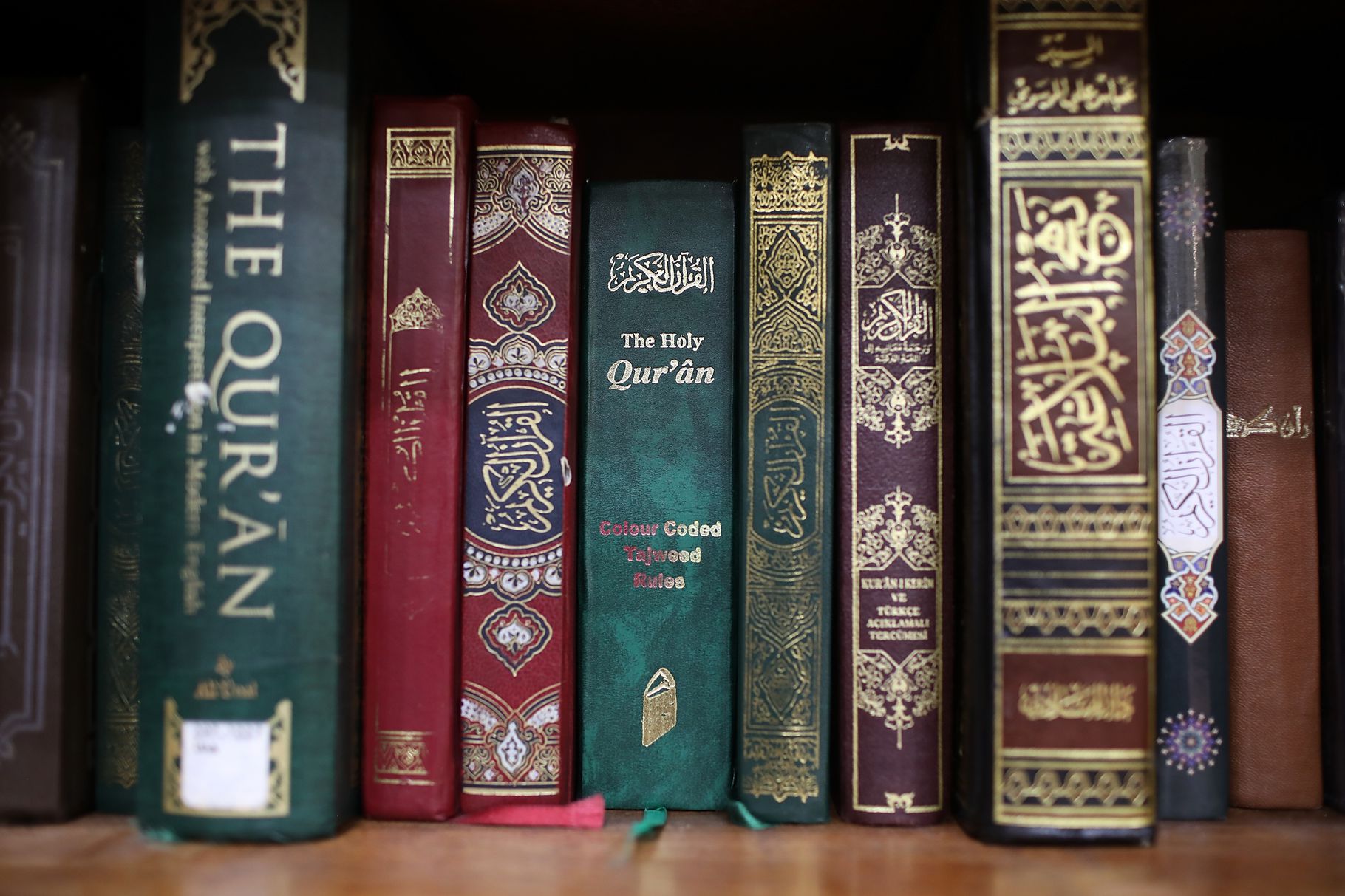

Islam’s Sacred Sources

There are two main textual authorities in Islam. The first is the Qurʾān (literally “reading” or “recitation”), which in the original Arabic, according to Muslims, contains the literal and direct words of Allah dictated by the angel Gabriel to the Prophet Muḥammad a few verses at a time over a period of 23 years, from 610 AD until shortly before Muḥammad’s death in 632 AD. The verses were written by Muḥammad’s followers as they were revealed, and they were compiled into a single text shortly after his death. Muslims believe that the Arabic Qurʾān in its present arrangement dates from the time of the Caliph Uthman ibn Affan, who reigned from 644 AD to 656 AD. The second textual source is the Prophetic Traditions, narratives by or stories about the Prophet’s behavior and attitude in the early Muslim community, known as aḥādīth.

The word ḥadīth in Arabic literally means a story or narrative. Ḥadīth as a technical term in Islam means a story about the Prophet Muḥammad. Such stories contain the sunnah (lit. practice) of the Prophet, detailing his words and actions, or those things of which he tacitly approved (things that he witnessed others doing or saying and did not correct or criticize). The stories were passed on orally for generations before being collected and written down. The collections of aḥādīth used today by Muslims were compiled in the second half of the ninth century AD, approximately two and one half centuries after Muḥammad. Of the more than half a dozen ḥadīth popular collections used by Muslims, the most well-known and respected are Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī and Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim. While the Qurʾān lays out general principles, the Prophet and the early community serve as practical examples of how to incorporate and implement those principles in the daily lives of individuals and societies. Both the Qurʾān and the Prophetic Traditions inform Muslim belief and practice related to women.

The Qurʾān And Women

“The submitting men and the submitting women, the believing men and the believing women, the obedient men and the obedient women, the truthful men and the truthful women, the patient men and the patient women, the reverent men and the reverent women, the charitable men and the charitable women, the fasting men and the fasting women, the chaste men and the chaste women, and the men and women who remember Allah frequently — Allah has prepared for them forgiveness and a great reward.” (Qurʾān 33:35)

The above verse provides the framework in which Muslims see the status of women in Islam. Both men and women are responsible for performing the same religious duties, and both can expect to reap the same spiritual rewards. Both are thus equal in the sight of Allah. Likewise, 3:195 echoes the notion of male and female spiritual equality:

“And their Lord has accepted of them, and answered them: “Never will I suffer to be lost the work of any of you, be he male or female: You are members, one of another: Those who have left their homes, or been driven out therefrom, or suffered harm in My Cause, or fought or been slain,- verily, I will blot out from them their iniquities, and admit them into Gardensu with rivers flowing beneath; A reward from the presence of Allah, and from His presence is the best of rewards.”

Both man and woman were created from “a single soul,” according to the Qurʾān (4:1), and thus share the same essence. The sense of spiritual equality is augmented by recognition of Adam and Eve’s mutual responsibility in disobeying Allah by eating the forbidden fruit: “And they both ate from it. They became conscious of their nakedness and began to cover themselves with leaves from the garden” (20:121).

Stories Of Women In The Qurʾān

The status of women is further highlighted by the stories of women that are told in the Qurʾān. Mary, the mother of Jesus, is honored with her own chapter. Chapter 19 of the Qurʾān is titled “Mary,” in which the story of the annunciation and birth of Jesus is told. Jesus is identified throughout the Qurʾān as “the Messiah, son of Mary.” Mary’s name appears thirty times in the Qurʾān. Other women whose stories appear in the Qurʾān are the mother and sister of Moses; the wives of Adam, Abraham, Noah, Lot and Pharaoh; and the Queen of Sheba. Each of these women plays a key role in the Qurʾānic accounts of sacred history. Of these, only the wives of Noah and Lot are held up by the Qurʾān as examples of disbelieving women. The rest are cited as examples of believing women.

The stories of the wives of Pharaoh, Noah, and Lot demonstrate the moral and spiritual independence of women. Pharaoh is one of the most egregious disbelievers described in the Qurʾān. His wife, however, is cited as an example of a believer who is destined for paradise (66:11). The wives of Noah and Lot are cited as examples of disbelievers who are destined for hell in spite of being married to two of Allah’s messengers (66:10).

The spiritual fate of the women is based solely on their own beliefs and actions. The men in their lives have no responsibility for their final destiny. This Qurʾānic framework of spiritual equality is widely accepted by Muslims, but other verses have traditionally served as the basis on which a temporal hierarchy has been established.

Chapter 4 of the Qurʾān is titled “The Women” (al-Nisaʾa). It is in this chapter that many of the injunctions dealing with family matters such as marriage and inheritance are found. The rights granted to women in the Qurʾān are seen by Muslims as a revolutionary departure from the customs of pre-Islamic Arabia, where female infanticide was common and women were not guaranteed a share of inheritance and could, themselves, be inherited as property. The Qurʾān outlaws female infanticide (16:58–59, 17:33) and inheriting women (4:19) and guarantees women a share of inheritance (4:7).

Family Relations: Marriage, Divorce, Inheritance

The Qurʾān encourages marriages (24:32) and provides specific instructions on the requirements and etiquette of marriage. The spousal relationship is described eloquently in the Qurʾān: “And among His Signs is this, that He created for you mates from among yourselves, that ye may dwell in tranquility with them, and He has put love and mercy between your (hearts): verily in that are Signs for those who reflect” (30:21). Husbands and wives are also described as each other’s garments (2:187). The Qurʾān portrays marriage as a warm and loving relationship, while also dealing with practical matters. A written contract and a dower (mahr) are required for a valid marriage (4:24–25). Unlike the Western concept of dowry, which is paid by the bride or her family to the groom, it is the Muslim groom who must pay the bride. The amount of the dower is agreed on by the couple and becomes the wife’s property, to do with as she pleases (4:4, 24). The terms of the marriage contract are also mutually agreed on by the couple and binding on both. Either party may stipulate any condition that does not violate the teachings of the Qurʾān.

The Qurʾān deals with marriage in detail, and it deals with divorce in even greater detail. Although a man may unilaterally declare a divorce without judicial process, the Qurʾān places conditions and restrictions on divorce that protect the interests of women and children. Among these conditions is arbitration that includes representatives of both the husband and the wife (4:35). Men are prohibited from taking back the dower and from treating their wives harshly (4:19–25). Another safeguard for women is the mandatory waiting period of three menstrual cycles before a divorce is final. In case of pregnancy, the divorce is not final until the woman gives birth. During the waiting period, the husband must provide support and lodging for the wife (65:2). After a divorce, a father is required to support his children, even if they live with the mother, and if the mother is nursing his child, the father must continue to support her as well (2:233). Along with these distinctly woman-friendly ideas and ordinances, the Qurʾān also contains verses that have been used to establish and maintain a gender hierarchy in Muslim societies. Most notable among the verses used to establish a gender hierarchy in which the man is the head of the household is 4:34. Differences in translations reveal important differences in the interpretation of this verse. One of the most popular English translations of the Qurʾān is that of Yusuf Ali. The Yusuf Ali translation of Qurʾān 4:34 reads:

“Men are the protectors and maintainers of women, because Allah has given the one more (strength) than the other, and because they support them from their means. Therefore the righteous women are devoutly obedient, and guard in (the husband’s) absence what Allah would have them guard. As to those women on whose part ye fear disloyalty and ill-conduct, admonish them (first), (Next), refuse to share their beds, (And last) beat them (lightly); but if they return to obedience, seek not against them Means (of annoyance): For Allah is Most High, great (above you all).”

There are a number of aspects of this verse on which various interpreters disagree. The first relates to the term that Yusuf Ali translates as “protectors and maintainers” (qawwamunʾala), which is understood to define the male–female dynamic. Yusuf Ali’s translation captures a general concept on which Muslims tend to agree — that men bear primary responsibility for the physical protection and financial support of women. Where interpretations differ on this part of the verse is the degree and nature of authority granted to men over women. Muhammad Pickthall’s translation of qawwamunʾala is “in charge of.” Where Yusuf Ali’s translation highlights men’s responsibility toward women, Pickthall’s highlights men’s authority over women. Both responsibility and authority are facets of the man’s position as head of the family. Patriarchal interpretations emphasize male authority, while feminist interpretations emphasize male responsibility and even make authority contingent on responsibility.

Perhaps the most controversial portion of 4:34 occurs near the end, where men are advised on how to deal with, according to Yusuf Ali, “those women on whose part ye fear disloyalty and ill-conduct,” or according to Pickthall, “those from whom ye fear rebellion.” It is in this context that the issue of corporal punishment arises. Yusuf Ali translates the Qurʾān’s advice this way: “admonish them (first), (Next), refuse to share their beds, (And last) beat them (lightly).” Pickthall renders the sentence as “admonish them and banish them to beds apart, and scourge them.” Although most translators and interpreters understand this verse to allow husbands to engage in some type of corporal punishment, a few contemporary translators offer an entirely different understanding. For example, the Progressive Muslims and the authors of the Reformist Translation, such as Laleh Bakhtiar and Amina Wadud, render this segment as: “advise them, and abandon them in the bedchamber, and separate from them,” applying the metaphorical interpretation, “separate from them,” to the Arabic phrase idribuhunna, which more traditional translators render as “beat/scourge them.” The metaphorical reinterpretation of the verse may be said to reflect contemporary disapproval of corporal punishment. However, even among those who understand the verse to allow corporal punishment there is general agreement that any such punishment must be minimal and non-injurious, which led Yusuf Ali to insert the adverb “lightly” in parentheses. Strict limitation on the severity of any corporal punishment is seen throughout the history of Muslim interpretation, appearing as a Prophetic admonition in the ḥadīth collections and scholarly commentary found in Qurʾānic commentaries.

Another area of dispute is what is meant by the term nushūz, which Yusuf Ali translates as “disloyalty and ill-conduct” and Pickthall translates as rebellion. Immediately preceding this mention of fear of disloyalty and ill-conduct or rebellion, the verse describes righteous women being devoutly obedient and guarding what Allāh would have them guard, as Yusuf Ali translates it. Elsewhere in the Qurʾān, believers are said to guard their chastity (23:5), so at a minimum, this is understood to refer to the wife’s sexual fidelity. However, it is also extended to include protection of the husband’s wealth, property, and other vital interests in his absence. Once again, the emphasis in Yusuf Ali’s translation is on responsibility, which is now reciprocal. The husband is responsible for the protection and maintenance of his wife and the wife is responsible for safeguarding her husband’s interests in his absence. Pickthall’s translation again emphasizes male authority and the fear of female rebellion against that authority. In common usage, the term nushūz has been linked only to women in the context of marital discord. However, it is important to note that the Qurʾān applies the term equally to men in the same context (4:128). Muslim scholar Heba Raouf Ezzat, described by wamda.com as one of “the 100 most influential Arabs on Twitter,” highlights this neglected dimension of family politics, showing that, while the Qurʾān orders men to keep domestic conflicts private, women may seek help from their extended family and community, which provides greater privacy for women in domestic conflicts.

Qurʾān 4:34 is not the only verse that is seen as establishing a gender hierarchy in Islam. In the discourse on divorce, the Qurʾān says: “women shall have rights similar to the rights against them, according to what is equitable; but men have a degree (of advantage) over them” (2:228). Within the specific context of divorce, this is understood to refer to the fact a man can unilaterally declare his wife divorced, whereas a woman who wishes to divorce her husband must seek a divorce from a Muslim judge. However, some scholars understand the degree that men have over women in a more general sense. Here, as in the case of 4:34, the emphasis may be on male authority or on male responsibility.

The Qurʾānic ruling on inheritance assigns the son a share equal to that of two daughters (4:11). Read alone, this may appear to privilege sons. However, because men are understood to bear complete financial responsibility for the women in their families, on the basis of 4:34, the distribution of inheritance outlined in 4:11 is seen as fair and equitable. A woman, at least ideally, is not financially responsible for anyone, including herself, whereas a man is responsible for not only his wives and children, but also for his widowed mother and his unmarried sisters.

The division of inheritance in 4:11, together with 2:282, which calls for financial contracts to be attested by “two witnesses, out of your own men, and if there are not two men, then a man and two women,” has led some to argue that a woman is equal to half a man. Others argue that this understanding is the product of an overtly patriarchal society that did not consider women eligible to engage in legal and commercial transactions in the first place.

Crime And Punishment

In issues of crime and punishment, the Qurʾān also demonstrates a mix of equality and disparity. In the case of theft, the text says: “As to the thief, male or female, cut off his or her hands: a punishment by way of example, from Allah, for their crime” (5:38). Just as good actions are given equal rewards for both men and women, the evil act of theft incurs the same punishment. This is also the case with adultery, according to 24:2, which states that men and women guilty of adultery are both subject to one hundred lashes. Where the disparity seems to appear is in 4:15, in which women found guilty of “lewdness” are ordered to be confined to their homes until death or until Allah “ordains another way” for them. On the basis of ḥadīth, most scholars hold that the punishment given in 24:2 is the other way ordained by Allah and the latter verse abrogates the former, solving the apparent disparity. Yusuf Ali disagrees with this interpretation and understands “lewdness” in 4:15–16 to refer to homosexuality, specifically to female homosexuality in 4:15 and male homosexuality in 4:16. Understanding “lewdness” as homosexuality in 4:15–16 solves the apparent discrepancy between these verses and 24:2, but it raises a serious discrepancy between 4:15 and 4:16. In the first, women guilty of homosexuality are punished by life imprisonment, whereas men receive no specific punishment and may be left alone. Yusuf Ali appears to be unique in understanding these verses to be addressing homosexuality, but his thinking deserves scrutiny because his translation remains one of the most popular English translations of the Qurʾān.

Aḥādīth And Women

As previously noted, the Qurʾān is not the only source to which Muslims turn for information on women. The Prophetic Traditions contain not only direct commands of the Prophet to and about women; they are also a rich source of detailed information on the women in the Prophet’s life and his relationships with those women. According to aḥādīth, the first person to believe in the Prophet’s message was his wife Khadīja. It was she who offered him comfort and support in the traumatic aftermath of his first revelatory experience, when he thought himself to be going mad. On hearing of his experience, she took him to her cousin, a Christian monk with knowledge of Hebrew Scriptures, who confirmed for Muḥammad the validity of his experience. Her support continued to sustain Muḥammad during the first difficult years of his mission. The Prophet’s later wives are among the most important transmitters of aḥādīth. These stories portray the Prophet as a loving husband and father who delighted in the company of his wives and daughters. The Prophet advised his companions that the best of them were those who treated their wives best. Like the Qurʾān, aḥādīth affirm both the spiritual equality of men and women and the traditionally accepted gender hierarchy, as the Prophet is reported to have said, “women are the twin halves of men,” (Sunan al-Tirmidhi, Book 1, ḥadīth 113) and also, “if I were to command anyone to prostrate before another, I would command women to prostrate themselves before their husbands, because of the special right over them given to husbands by Allah” (Sunan Abu Dawud, Book 11, ḥadīth 2135). There are thousands of aḥādīth in the canonized collections, and here, too, patriarchal interpretation has dominated Muslim understanding and use of the texts. As in the case of the Qurʾān, the contemporary period has witnessed scholarly challenges to patriarchal interpretations of the aḥādīth.

Sexual Modesty And Veiling

Perhaps no topic has dominated public discourse on women in Islam in the twenty-first century as the veil, whether it is the headscarf (hijab) or face veil (niqāb). A number of countries have discussed banning or restricting head and/or face covering. The French law popularly known as the Burqa ban, which went into effect in April 2011, received tremendous international attention. Under the law, women can be fined for covering their faces in public. Earlier, in 2004, France outlawed the wearing of “conspicuous religious symbols,” which includes Muslim headscarves, in public schools. Although the earlier law also restricts the wearing of other religious attire, it was popularly called the “Hijab ban” because Muslims were widely perceived as the primary target of the legislation. Turkey, a secular Muslim country, prohibits wearing headscarves in government buildings, including schools and libraries. Over the years, a number of attempts have been made by Egyptian authorities to prevent women from wearing face veils in public schools. Women who wear the niqāb have challenged these efforts in the Egyptian courts with mixed results.

The legal discourse on veiling and efforts to ban or restrict it have made it a political issue, a question of personal religious liberty, rather than a religious question of proper attire. What is lost in that discourse is the fact that Muslims disagree on whether covering the head and/or face is a religious obligation. Here too, interpretations of the Qurʾān and aḥādīth vary. Muslims do agree that the Qurʾān requires sexual modesty of both men and women. Both are told to lower their gaze and guard their modesty/chastity (24:30–31). Women are further admonished to cover their cleavage/bosoms with their coverings and conceal their beauty from men outside their families, except “what is ordinarily apparent of it” (24:31). This is where interpretation comes into play. As Fatima Mernissi points out, the Arabic word “hijab” is never used in the Qurʾān to refer to women’s clothing, nor is there any command to cover the head. Others argue on the basis of aḥādīth that “what ordinarily appears” of a woman’s beauty is the hands and face and that everything else must be covered. This is the most common understanding, which is why so many Muslims and non-Muslims alike believe that head covering is mandatory for Muslim women. The word niqāb is also taken from the aḥādīth. Though it appears in the context of being prohibited on the pilgrimage, those who argue for covering the face see this as evidence the Prophet’s wives covered their faces and believe that following their example is the ideal.

There is a growing resurgence of veiling among Muslim women throughout the world. Women who choose to wear either a head scarf or face veil do so out of a sense of piety and pride in their identity as Muslims. Women who choose not to wear either a head scarf or face veil are equally committed to their faith and their identity as Muslims.

The Qurʾān presents men and women as spiritual equals who are individually responsible for their beliefs and actions in this world and the next, and women are clearly granted particular rights and protections by text. At the same time, however, there are verses of the Qurʾān that serve as the basis for a gendered hierarchy within the family and society, and these have been and are used to privilege men over women. The responsibility for and authority over women granted to men within that gendered hierarchy are sometimes offered as reasons for restricting women in order to protect them.

Conclusion

There are more than a billion Muslims in the world, at least half of whom are women. The experiences of Muslim women are as varied as the women themselves. Some cover their heads, some do not, and some veil completely. They are daughters, sisters, wives, mothers, grandmothers, and aunts. Many are oppressed, and many are not. Many who are oppressed fight that oppression through their commitment to their faith, a faith with ongoing interpretive traditions in which Muslim women are actively involved. The gender hierarchy discussed in this article is seen by a number of contemporary Muslim scholars as the result of patriarchal interpretations, interpretations that are not in keeping with the Qurʾānic emphasis on the spiritual and religious equality of men and women discussed herein. These scholars, such as Amina Wadud in Qurʾān and Woman: Rereading the Sacred Text from a Woman’s Perspective and Asma Barlas in “Believing Women” in Islam: Unreading Patriarchal Interpretations of the Qurʾān, call for a new approach to the texts. Fatima Mernissi, in her seminal work, The Veil and the Male Elite: A Feminist Interpretation of Women’s Rights in Islam, addresses misogynistic uses of aḥādīth and to challenge the centrality of the veil as a symbol of female piety. The works of these and other Muslim women scholars and activists underscore the gap between how Muslim women see their rights and the struggle for them and how they are seen by secularists and non-Muslims. Such scholars and activists play a crucial role in the ongoing reinterpretation of their religion and in changing the images of Muslims around the globe.

Women At The Rise Of Islam

701 – 017

Last Updated: 11/2021

Copyright © 2017-2021 Institute for the Study of Islam (ISI) | Institute-for-the-study-of-Islam-org | Discerning Islam | Discerning-Islam.org | Commentaries on Islam | © 2020 Tips Of The Iceberg | © 1978 marketplace-values.org | Values In The Marketplace | are considered “Trade Marks and Trade Names” ®️ by the Colorado Secretary of State and the Oklahoma Secretary of State. All Rights Reserved.