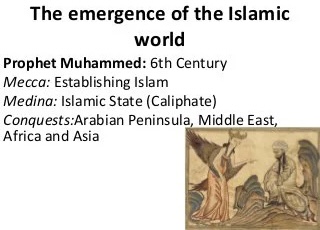

The Warrior-Defenders Of The Faith

The Muslim world faced the military powers of European imperial expansion in many different areas. In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century an important part of the Muslim response took the form of jihads organized by more traditional movements of Islamic renewal. Many of these early movements had begun as efforts of reform within society and were only later drawn into conflict with European forces. By midcentury, however, new movements of Islamic revival developed in direct response to European attack, although the older type of evolution from movements of local renewal to jihads defending against imperial expansion continued to be important. Some of the most effective efforts of military opposition to European expansion were these movements, while the newly modernized armies of the larger Muslim states proved to be much less of an obstacle to the European forces.

The emerging warrior-defenders of the Muslim world were not Luddite opponents of new technologies or methodologies. When modern weapons were available, they were used by the renewlists. The strength of these movements, however, came from their abilities to mobilize large numbers of people in organizations whose formats were familiar. Most frequently, the new defense groups were Sufi tariqahs in structure, in their self-definition, and in their leadership. An additional source of strength for these movements was that they were able to use the tactics of guerrilla warfare of a modern style long before these had been more formally defined by Mao Zedong.

Militant jihad movements were not as important a factor in the large central Muslim states as they were in other parts of the Muslim world during the nineteenth century. Significant movements of explicitly Islamic reform did develop in the central Ottoman lands. However, they were not actively advocating jihads, nor were they within more traditional organizational formats that provided a basis for militant renewal movements in other parts of the Muslim world. Instead, this reformism that developed in the second half of the nineteenth century would later be called “Islamic modernism.” Major governmental reform programs in the central lands of the Ottoman Empire were primarily efforts in modernization using Western models and inspiration rather than being actions of Islamic renewal and were part of the rulers’ ongoing activities to strengthen the empire.

Movements that sought to affirm a historical identity or tradition often developed in nationalist rather than religious forms. Nationalism among the non-Muslim peoples within the Ottoman Empire developed as an early and powerful force of opposition. Later in the century nationalist sentiments also were manifested among Muslims in the empire who advocated significant change, either demanding recognition of their rights as citizens within the empire or independence. In this way assertions of identity and demands for political reform among Arabs in the Ottoman Empire began to be articulated in nationalist terms by the end of the century. During World War I, when there was a significant revolt against Ottoman rule in Arab lands, even though it was led by the Grand Sharif of Mecca, the movement was known as the “Arab Revolt” and made no claims of offering a program of Islamic renewal. Although the Grand Sharif suggested that he might be named caliph, this was a political proposal rather than a statement of advocacy for a program of Muslim revival. In Egypt the dynasty established by Muhammad Ali achieved a high degree of autonomy within the Ottoman Empire and was actively reformist in policy, but its program was based on westernization rather than Islamic renewal. Late in the century, similarly, the emergence of a movement of Egyptian nationalism sometimes made appeals for popular support in Islamic terms, but it was primarily a nationalist movement in more secular and Western terms than an Islamic movement.

In Qajar domains, governmental reform was also in the framework of attempting to modernize in the Western mode. Outside of the movement of the Bab, there was little popular mobilization for explicitly Islamic motivations of reform or societal transformation. By the end of the century new Iranian nationalism was beginning to emerge as a synthesis of more traditional groups with those created by the economic and cultural changes of the modern era. The opposition to the Tobacco Concession of 1890 and the Constitutional Revolution of 1905–06 were crucial parts of the transformation of Iranian politics but in many ways were not basically movements of Islamic renewal.

Militant movements did develop in the third major central Muslim state, the Mughal sultanate of India, and this reflected the militancy and renewalism of the transitional era, which in many ways were parallel to the movement of Sayyid Ahmad Barelwi. A student of Barelwi, Titu Mir (1782–1831), returned to his home of western Bengal and gathered a group of followers, who formed a separate community distinguished by dress and dietary restrictions. Titu Mir emphasized strict adherence to Islamic law and soon came into conflict both with the Sufi orders and the local landlords, who feared his ability to arouse and organize their peasant tenants. After he declared a jihad, he was killed in 1831 by the military forces sent to suppress his uprising. Similar to some other movements of the time, Titu Mir attempted to create an alternative society.

A more significant and broad-based militant movement developed in eastern Bengal under the leadership of Hajji Shariat Allah (1781–1840), who was born in Bengal and had lived and studied for an extended period of time in Mecca. When he returned to Bengal, he organized an effort to impose a stricter observance of the faraid (religious duties), and his movement became known as the Faraidi. He gained a large number of followers, especially among the peasants and workers, who were increasingly oppressed by British plantation owners and Hindu landlords. Following his death in 1838, his son, Dudu Mian (1819–62) gave the movement a more explicitly communal organization with a hierarchical administrative organization. The Faraidi clashed with authorities, and Dudu Mian was jailed a number of times.

The more explicitly Islamic movements that resulted in militant opposition to existing conditions and the declarations of jihads were not primarily aimed at combatting the expansion of British control in India. They did involve conflict with British authorities, however. The largest uprising to be specifically directed against the British in the nineteenth century was the great revolt in 1857, sometimes called the Sepoy Mutiny. The cumulative pressures of British policies helped to create conditions within which growing Indian frustration expressed itself in a widespread revolt against British authorities in which Muslims and Hindus joined together. The British crushed opposition severely and formally abolished the Mughal sultanate, as well as bringing an end to the administration of the British East India Company. A wide spectrum of Muslim leaders participated, but the uprising did not assume the character of a unified jihad. Despite the fact that many British officials continued to believe that there was a major threat to British rule from Muslim militants, the events of 1857 marked the end of the era of potentially effective jihad movements in South Asia until well into the twentieth century.

Warrior-defenders of the faith were more active in a number of the Muslim world’s frontier areas. Although the movements continued to be inspired by renewalist traditions, many came to be increasingly involved in efforts of opposition to expanding European control and less concerned with the purification of local practices. Some movements were direct continuations of earlier renewal movements, while others represented new organizations or traditions.

In a number of areas, Sufi orders provided a framework for some of the most effective resistance to European imperial expansion. In the Caucasus region the foundations laid by Naqshbandi shaykhs earlier in the century opened the way for leaders to organize jihad opposition to Russian imperial rule as the Russians attempted to consolidate control in the region. A series of active imams inspired the peasants in the region, especially in Chechnya and Dagestan, to rise in jihad against the Russians. These imams continued the dual emphasis of fighting the foreigners and insisting on rejection of local religious customs, replacing them by a more strict adherence to Islam. In this way the Naqshbandi holy wars were an important part of the Islamization process of the societies as well as a significant deterrent to imperialist expansion. The jihads began in the 1820s and reached their peak of effectiveness under the leadership of Imam Shamil, who led the war effort from 1834 until 1859. Although the movement was defeated and its leaders killed or in exile, the Naqshbandiyyah and activist Islam remained a force in the region. There was another uprising in 1877, and in the interim period between the collapse of the czarist state and the establishment of Communist rule at the end of World War I, the Naqshbandiyyah established a short-lived imamate. The long-term impact is reflected in the fact that a portrait of Imam Shamil continues to have a place of honor in offices of officials in post-Soviet Dagestan.

The Qadiriyyah tariqah developed along parallel lines in the Caucasus and was at times in alliance with the Naqshbandiyyah order; at at other times they were competitors for influence and support. The Qadiriyyah was brought to the region by Kunta Haji Kishiev, who was born in Dagestan and lived in Chechnya. He joined the order while on pilgrimage, and on his return in 1861, after the defeat of Imam Shamil, he advocated acceptance of Russian rule and was less puritanical in his devotional path. He gained a large following in a region that was exhausted by decades of fighting, and Qadiri teachers successfully continued the process of the conversion of the Ingushetians (people who lived in a region north of the Caucasus Mountains and west of Chechnya), whose conversion was completed by the 1870s. The Russian rulers feared the rapidly growing tariqah, however, and arrested Kunta Haji, who died in prison in 1867. The members of the Qadiriyyah took an active role in the major revolt of 1877, joining with the Naqshbandiyyah. Although advocacy of a jihad was abandoned, both orders were major forces, with Qadiri influence strongest in Chechnya and the Naqshbandiyyah strongest in Dagestan.

French imperial expansion in North Africa in the first half of the nineteenth century found its most effective opponent in a leader of the Qadiriyyah tariqah, the amir Abd al-Qadir (1808–83). The French invaded Algeria in 1830 and rapidly conquered the coastal cities, bringing an end to Ottoman rule in the country. Abd al-Qadir’s father, Sidi Muhyi al-Din al-Hasani, was the head of the Qadiriyyah in the region, and he declared a jihad against the European invasion. Abd al-Qadir assumed leadership of the resistance and soon worked to establish a Muslim state in which he took the title of the commander of the believers. The new community was to be a state organized in the traditions of renewalism as well as an army engaged in jihad. The combination of the state organization and the Sufi foundations for loyalty created an effective vehicle for mobilizing tribal opposition to the French as well as creating a new military force.

Abd al-Qadir and the French alternated between open war and negotiations. At one point in the conflict in 1837, there was a treaty that provided mutual recognition for the French rule in the urban areas and Abd al-Qadir’s authority in some interior areas. Hostilities resumed, however, and the French finally defeated Abd al-Qadir’s forces in 1847. Abd al-Qadir went into exile, finally settling in Damascus, where he died.

Most effective resistance to the French ended with the defeat of Abd al-Qadir, but there were some significant opposition movements after 1847. There were a number of movements led by people claiming messianic authority, which were rapidly suppressed. In this turmoil a recently established tariqah, the Rahmaniyyah, played an important role. In 1870–71 the various movements of local discontent were brought together in a major uprising when a local administrator, Muhammad al-Muqrani, worked with leaders of the Rahmaniyyah order in eastern Algeria to oppose French rule. After the defeat of the opposition forces, the French confiscated large amounts of land and worked to complete the process of the destruction of Algerian Muslim society.

The combination of renewalist reform of Muslim society with a jihad against foreign control within the organizational framework of Sufi orders continued to be one of the most visible modes of Islamic reform in many areas of the Muslim world in the nineteenth century. The long tradition of such reform movements in West Africa continued with great strength throughout most of the century. The successors to Uthman dan Fodio in the jihad states maintained an advocacy of renewalism but now within the framework of an established state structure. This meant that when Great Britain established control in Nigeria, the leaders of the dan Fodio tradition represented states that came to an agreement with the British rather than creating a new jihad movement.

In the Senegambia region, the Tijaniyyah order was a vehicle for a major renewalist jihad. Al-Hajj Umar Tal (1794–1864) combined many important lines of renewalism. He was born in Futa Toro, the heartland of the old jihad tradition, and went on a pilgrimage in 1826 to Mecca, where he was initiated into the Tijaniyyah. On his return to West Africa he stayed in Sokoto, where he married a granddaughter of Uthman dan Fodio. When Umar arrived back in his homeland, he began an major effort to oppose compromises with local religious customs and to create an authentically Islamic community. He created an army that used French weapons and gained a large following. He declared a jihad in 1852, conquered Futo Toro, and established a new jihad state of which he was the commander of the believers. Umar used the hierarchical organizational principles as well as many of the theological concepts of the Tijaniyyah order in creating his movement. Umar’s new state soon came into direct conflict with the French in the Senegal River valley. He was defeated in 1860 and signed a treaty with the French. In his reform activities he came into conflict with Muslim groups along the Niger valley, especially facing the Qadiriyyah order led by the Kunta family, who had emerged as a major force by this time. A coalition of forces opposed to Umar defeated and killed him in 1864. However, he had established a strong enough political system so that his son succeeded him as ruler of a smaller state centered around Hamdallahi in the Niger bend region, which lasted until the French conquest of the area in 1893.

The vitality and appeal of the renewalist message, as well as its viability in the context of nineteenth-century West Africa, are shown by the number of other jihad movements that were relatively successful. Each movement built on a base of reformist mission and worked to establish a separate and authentic alternative community. For example, Ma Ba (1809–67), a teacher in Gambia, declared a jihad against the political leaders of his area to establish an Islamic state. He was aided by Lat Dior, a local ruler who had been deposed by the French and who continued the efforts to expand the Islamic state after Ma Ba’s death in 1867. These and other smaller jihad efforts resulted in the effective conversion of the Wolof people to Islam and hastened the Islamization of society.

In many ways the final phase of the older jihad tradition in West Africa came with the career of Samory Ture (ca. 1830–1900), who was born in Guinea and spent his early life as a merchant working in the area’s trade networks. He then became a soldier and a student in a small jihad state established by a local commander, More-Ule Sise, and in 1845 he succeeded Sise as the state’s leader. Samory transformed the state into a major conquest empire in the 1870s and 1880s. He created as modern an army as was possible at the time and established Muslim teachers as officials in his conquered territories to ensure compliance with Islamic law. He actively destroyed non-Islamic religious sites and cult symbols. He came into conflict with the French and came to an agreement with them that caused him to shift his state to the east in the upper Volta region. In the 1890s, however, Samory fought with both the French and the British, was defeated in 1898, and died in exile in 1900.

In the 1890s British and French military expansion brought European control to all of the areas of western and central Africa. The existence of an independent African-ruled state in any form was no longer possible. The long tradition of the jihad states came to an end as Samory was defeated, the last of the followers of al-Hajj Umar Tal were conquered, and the territories of the Sokoto caliphate were occupied by the British. For two centuries, however, the combination of a renewal mission, opposition to local non-Islamic customs, and defense against foreign rule provided a highly successful format for the efforts to create alternative, authentically Islamic communities and states. For a time these jihad states were more effective than virtually all other alternatives in resisting European expansion.

In Southeast Asia much of the region had already come under European control by the midcentury, and even the early nineteenth-century warrior-defenders had been engaged in major anti-imperialist jihads. During the second half of the century, in broad terms, there was a significant development of greater involvement in activities of Muslim piety. Much of this was related to the impact of European expansion. The opening of new transportation facilities meant that many more people went on the pilgrimage to Mecca, and the expansion of modern means of communication meant that many more Muslims in Southeast Asia had access to the world of Islamic learning. A significant community of scholars from Southeast Asia developed in Mecca, and pilgrims studied with these scholars and became affiliated with major tariqahs. On their return home, the orders provided structure for renewalist activities. These developments created a larger audience of support for Muslim renewalism, although this did not inevitably involve jihad.

The Dutch did face significant revolts representing the opposition of the Muslim scholar class and peasants, however, which was expressed in terms of renewalist Islamic opposition to both the Dutch and those local elites who worked with the imperial rulers. In western Java there was a major uprising against the Dutch in 1888 in which the Qadiriyyah tariqah played a major role. One of the longest jihads was the wars in Acheh, in northern Sumatra, which lasted from 1871 to 1908. By the end of the nineteenth century the Dutch began to implement policies that sought to work with less militant ulama rather than viewing all Muslim movements as threats to Dutch rule. This helped to bring an end to the era of jihads of the old renewalist style. By the early twentieth century opposition to the Dutch began to take on a more nationalist and less religious tone.

One of the last traditionally conceived jihads organized by Sufi leaders against the European imperial powers was in Somalia. In the late nineteenth century the Somalis faced a number of challenges. The Ethiopian empire was expanding, but more important, in the “scramble for Africa” in the late nineteenth century Italy, France, and Great Britain all hoped to gain control of Somali territories. Territories of various Somali clans were being conquered by these forces, but the Somalis had no centralized organization to develop effective opposition. Somali society was held together by a shared language and poetic traditions and structures of clan relationships rather than by a more unitary state. The major ties that transcended clan loyalties were affiliations to Sufi orders, the largest of which was the Qadiriyyah. It was Sufi organization that provided the basis for the Somali battle against imperial expansion at the end of the nineteenth century.

The leader of the jihad in Somalia was Muhammad Abdallah Hasan (1864–1920), a scholar who combined knowledge of Islamic law and activist Sufism with a great poetic talent that made his message readily accessible to all Somalis. He was born in north-central Somalia into a family with some reputation for Islamic learning and piety. He received a standard Muslim education, traveling as a young man to such regional centers of Islamic learning as Harer and Mogadishu. In 1893–94 he went on a pilgrimage and studied for a time in Mecca and Medina. While there he came into contact with Shaykh Muhammad ibn Salih al-Rashidi, who initiated him into his newly established order, the Salihiyyah. This order was part of the broader cluster of tariqahs following the tradition of Ahmad ibn Idris and helped to confirm in Muhammad Abdallah Hasan a sense of renewalist mission. Muhammad Abdallah Hasan returned to Somalia in the late 1890s and began a campaign of opposition to local practices of veneration of holy men and other activities, such as the use of tobacco, coffee, and qat (whose leaves are chewed as a stimulant), which were not in accord with a strict interpretation of Islamic fundamentals. He worked to promote a life of strict piety and began the process of establishing a separate communal association that was tied together within the format of the Salihiyyah order. This brought him into conflict with another important, newly established tariqah in Somalia, the Uwaysiyyah, a branch of the Qadiriyyah organized by Shaykh Uways al-Barawi (1847–1909).

Uways had left his homeland of southern Somalia for a pilgrimage and study and received extended instruction in the Qadiriyyah at the center of that order in Baghdad. The Uwaysiyyah believed in the importance and efficacy of the mediation of holy men, and the traditional practices of tomb visitation were an important part of the devotional life of the Uwaysiyyah. Uways was also willing to work with the rulers of the day, especially the sultans of Zanzibar, but he also made some accommodation with Italians. By the 1890s the Uwaysiyyah was a large and influential order along the East African coast. The Uwaysiyyah clashed with the Salihiyyah in many different ways, and some of this was reflected in exchanges of hostile poetry, because Uways was also a talented poet. The rivalry reached a climax when a group of members of the Salihiyyah attacked an agricultural settlement that Uways had established and murdered the shaykh in 1909.

By the time of the killing of Shaykh Uways, the primary war in which Muhammad Abdallah Hasan was engaged was a jihad against European imperialism. In 1899 he had declared a jihad against the British, Italians, and Ethiopians. For a short period of truce, his control was recognized in 1905 by the British and the Italians, but fighting soon resumed. The community that was given recognition by the truce arrangement emphasizes the similarity of the Salihiyyah’s efforts with other jihad groups in working to create alternative societies in which the message of Islam was comprehensively applied. The jihad soon resumed and continued throughout World War I, although the shaykh was unable to benefit from potential German and Turkish support. After the war in 1920 the British mounted a major military campaign that crushed the movement, and Muhammad Abdallah Hasan died in the same year in a hiding place to which he had fled. His jihad had succeeded in slowing European expansion in the Horn of Africa for almost two decades.

The Warrior-Defenders Of The Faith

803 – 032

Home

Last Updated: 04/2022

See COPYRIGHT information below.