The State And Religion

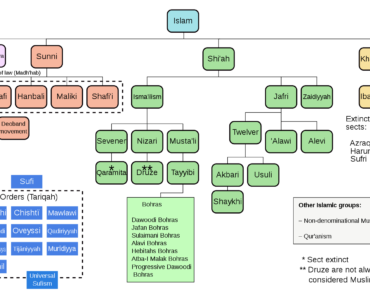

The emergence of new political and religious bodies raised again the problem of the division of authority between the state and religious institutions. In Middle Eastern societies this issue goes back to the ancient temple communities of Mesopotamia and the emergence of the first empires. Ever after, the boundaries of authority and functions between rulers and priests would be an open question. The Islamic era began with its own position on this issue. For Muslims the Prophet himself embodied both religious and political authority. He revealed God’s will and God’s law for his people; he was the ruler of the community, who also collected taxes, waged wars, and arbitrated disputes. The early caliphs also claimed religious authority to make pronouncements on religious law and beliefs as well as the prerogatives of emperors. In the evolution of the caliphate, however, the tendency to separate political and religious authority seemed unavoidable. As conquerors and emperors, the caliphs increasingly became political leaders with only a symbolic form of religious authority; the authority to promulgate or discover law, to make judgments on matters of belief, and to instruct ordinary Muslims devolved on the ulama and the holy men. By the time of the Abbasid empire’s collapse, political and religious authority thus belonged in practice to different people, although this was not yet recognized in theory.

The Turkish invasions and the establishment of nomadic or slave military regimes made acute the question of religious or state authority and functions. Nomads and slaves were foreigners in origin and culture, warriors imposed on the civilian populations, while the town and village elites of the post-Abbasid era were Muslim religious leaders. The division of personnel and realms of authority was patent. What would be the relation between the two elites: state military and administrative on the one hand or local, communal, and religious on the other? This problem was solved in the interregnum period by the creation of two autonomous but cooperating elites. Turkish nomadic and slave military authorities were eager to establish internal order, to facilitate taxation, and to minimize resistance from their subject populations. They needed the help of educated functionaries and scribes. They needed the legitimation and recognition that only the holders of religious purity could supply. They wanted the presence of cultivated scholars and holy men, poets, philosophers, historians, teachers, intellectuals, and artists to adorn and glorify their courts. They craved to enter into the fraternities of cultured Middle Eastern peoples.

The military elites thus sought the support of the religious elites by underwriting their activities. They lent their forces to the suppression of Shiism; they provided endowments for mosques and khanaqas and stipends for teachers, holy men, and students. Seljuk rulers constructed and endowed madrasas in every major city of their empires. They endowed Sufi khanaqas to foster the holy men who served as missionaries for Islam. Although Seljuk rulers at first patronized particular schools or factions, by the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, Middle Eastern rulers had worked their way to a pan-Sunni policy, supporting all the major schools of law, hadith, and theology. In return, the religious leaders accepted the Seljuk states, recognized their legitimacy, justified them to the subjects, and taught the necessity of obedience. They cooperated in routine administrative matters, occupying an intermediary position representing the regime to the people and the interests of the people to the regime. By the twelfth century the two elites of state and religion had worked out a policy of cooperation. A Muslim society became in practice a society governed by state elites, who protected and patronized Islam, and religious leaders, who legitimized alien states. This condominium of elites and cooperative relations between institutions would be for many centuries the Middle Eastern Muslim solution to the problem of state and religion.

Not all Middle Eastern peoples accepted this arrangement, however. Mountain, nomadic, and tribal peoples sought to maintain political independence, avoid economic subordination, and cultivate cultural autonomy. To unite disparate small communities, to organize and justify resistance to state control, many harked back to the image of the Prophet, embodying both political and religious authority, making political interests a holy cause and holy aspirations a worldly endeavor. Such groups often looked to Sufi holy men to provide them with unified religio-political leadership, sometimes in opposition to established states, sometimes in conquering ventures of their own. The Safavid empire had its origins in this alternative concept of Islamic religious leadership.

The State And Religion

803 – 014

Home

Last Updated: 04/2022

See COPYRIGHT information below.