The Ottoman State Apparatus And Religion

The Ottoman state was built on the very same institutional base as its Middle Eastern predecessors. At the center was the court or palace apparatus, the household of the ruler, comprising his family, his harem, his boon companions, and his highest ranking officers, administrators, and religious functionaries. The court served as an extended family and the government’s nerve center, a training institute for Ottoman cadres, and a theater of cultural display. Centered at the Topkapi Serai, overlooking the Golden Horn of Istanbul, the court was divided into two sections. The inner section was made up of the residences of the sultan and his harem, the treasury, and the school for pages and officers. In Ottoman society and politics the women of the royal family were particularly important. In the historic Turkish understanding, powers were vested not only in the reigning prince but also collectively in his family. Women were therefore important in the ceremonials of the regimes, in its charitable activities, and by their role in negotiations and intrigue at court. They were important in the selection of officers and policies. The outer section of the court was the administrative zone proper, including state offices and palace functionaries.

The nerve center of the Ottoman capital at Istanbul was the palace known as Topkapi Sarai. Unlike European palaces, it comprised a series of four concentric courtyards of ever-increasing privacy.

The city of Istanbul could be considered an extension of the royal palace. After the conquest, the sultan Mehmed found Constantinople rich in history but virtually abandoned by its population. The Ottomans resettled the city and built up its population not only with servants of the state but with useful communities of Muslims and minorities, who could do the commercial, craft, and other work essential to an expanding society. Successive sultans built great mosque and school complexes, provided with such facilities as hospitals, libraries, bazaars, bakeries, inns, residences, and soup kitchens. Such great complexes as the Selimiye and the Suleymaniye, named after the sultans who founded them, became neighborhood community centers for Istanbul’s population. Just as the Safavids built Isfahan, so too did the Ottomans rebuild Istanbul as an essential base of operations and adornment for their empire. At its apogee, Istanbul had a population of about seven hundred thousand, an enormous number for a sixteenth- and seventeenth-century city.

The military was essential to Ottoman power, and as early as the reign of the sultan Murad I (r. 1360–89) they had begun to build up slave forces to supplement, subdue, and replace free Turkish warriors. The Ottomans went further than any previous Middle Eastern regime to ensure the supply of slave soldiers. In the past, slave soldiers originally came from the Caucasus or from Central Asia, outside the areas in which they would serve. The Ottomans changed this by instituting the devshirme, a tax in manpower on the Christian population of the Balkans. This was both the first systematic recruitment of slaves and the first recruitment from within the domains of the state itself.

The fourth and most private of Topkapi courtyards contained freestanding garden pavilions in which the sultan and his intimates lived. The Baghdad Kiosk, built in 1638–39 to commemorate the victory of Murad IV at Baghdad, overlooks a garden and the Golden Horn.

The Ottomans created a further innovation in slave armies. Whereas most Middle Eastern slave forces were trained to be elite cavalry, with a keen sense for military and tactical innovation the Ottomans trained their most important units as infantry, provided them with firearms, and used phalanx tactics to combine massed musket firepower with artillery. Thus were born the famous janissaries and the tactics that made them for centuries the most advanced of European and Middle Eastern armies. In part a result of this innovation, the appellation Gunpowder Empire applies above all to the Ottomans. The Ottomans organized cavalry as well as infantry forces, but the cavalry forces were completely different in character from the janissaries. The cavalry were recruited among Turkish warriors. They were not garrisoned as a central army; rather, they were provided with incomes from land grants throughout the Ottoman domains. From their timars (the equivalent of the Arab iqtas) the timar holders provided local security and served in Ottoman campaigns. They were an old-fashioned quasi-feudal rather than a centralized army. The slave system was also used to build up a powerful bureaucratic apparatus. The Ottomans converted their young slaves to Islam and educated them in the palace schools to be pages in the royal household, officers in the army, or government officials. Whatever their origin, the slaves were united by devotion to the sultan and by their upbringing in the “Ottoman way.” Thus the regime was built not on ethnic homogeneity but on the slaves and clients of the rulers, coming from a variety of backgrounds, who by training and education were qualified as a ruling caste.

The domed mosque with pencil-thin minarets came to symbolize Ottoman domination throughout their realm. This detailed 1559 drawing of the Istanbul skyline by the German artist Melchior Lorichs shows the mosque complex Mehmet the Conqueror built immediately after he took the city in 1453.

Until the seventeenth century, when the Ottoman system began to break down, the political class was organized to prevent the accumulation of private power and its transmission to later generations. The slave system was the key to this concept, because only newly recruited slaves could be inducted into positions of power. Children of slaves could not be. Although middling administrators, sons of governors, and rich timar holders were sometimes able to pass estates to their children, Ottoman policies were inimical to the accumulation of private property. Large private fortunes could be and were readily confiscated. Unlike the Safavids, who failed to suppress tribal resistance to the state, the Ottomans progressively eliminated all rival organized political bodies and imposed a salaried bureaucracy in most of their provinces. Most tributaries were annexed and subjected to centralized rule. Eastern tribal populations were subordinated. Independent rural landowners and Sufi leaders were incorporated into the Ottoman state. Only a few remote provinces, such as Romania, the Crimea, and parts of eastern Anatolia, remained in the control of quasi-independent Greek, Turkish, and Kurdish tributaries. More than any other Middle Eastern state, the Ottomans succeeded in centralizing political power and overcoming tribal autonomy. They brought to an end in their region the historical struggle of tribes and states.

The sultans commissioned elaborate furnishings for their mosque complexes. This magnificent walnut box, designed to hold a manuscript of the Qur’an in thirty volumes, was ordered by Bayezit in 1505-06, probably for his mosque complex in Istanbul completed in the same year.

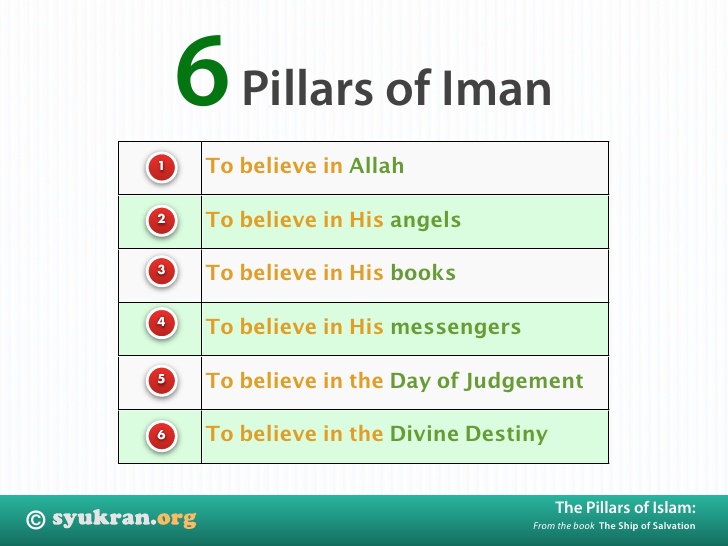

The Ottoman drive toward centralization was particularly marked in the domain of religion. Like the Seljuks before them, the Ottomans continued the practice of patronizing the ulama and the Sufis. They built mosques and madrasas. They endowed teachers and students; they organized judicial administration and employed religious scholars as judges and professors. They employed religious functionaries, such as notaries, registrars, and administrators of orphans’ and intestate properties. The Ottomans went further than their Seljuk predecessors, however, in that they not only patronized the religious elites, they incorporated them into a hierarchically ordered bureaucracy and made them functionaries of the state as well.

The position of shaykh al-Islam or chief mufti (a mufti was an expert in Islamic law and a member of the ulama establishment) dates to 1433. Originally, the man holding this position was the personal religious adviser to the sultan, and his office may have been created to increase the religious legitimacy of the state — perhaps to parallel the ancient caliphate and to respond to criticism about the regime’s secularization. The earliest muftis had no administrative functions; only late in the reign of Mehmed II was the chief mufti recognized as the head of the ulama. The power of appointing other ulama seems to have been given to the chief mufti in the middle of the sixteenth century.

The teaching system was also transformed into state offices. Whereas previous regimes had endowed madrasas in the important cities, the Ottomans gave them a hierarchical rank: those of the reigning sultan at the top, followed by foundations of earlier sultans, followed by madrasas founded by government officials and religious functionaries. By the middle of the sixteenth century the principle that a scholar had to serve in a graded series of colleges was firmly established. Professors were no longer merely appointed to teaching positions for life; now they could be promoted from one position to another. The schools were also organized by functions. The lowest-level madrasas were assigned to teach Arabic language and linguistic studies, astronomy, mathematics, theology, and rhetoric; the middle-level colleges taught literature and rhetoric; and the highest-level subjects were law and theology.

The judiciary was organized in a similar way. The original judicial positions were located in Istanbul, Edirne, and Bursa, but many positions were added in other cities in the late sixteenth century, probably to create new jobs for an ever larger cadre of position seekers. The positions in Istanbul, Bursa, and Edirne ranked at the top of the hierarchy, followed by those in Damascus, Cairo, Baghdad, Medina, Izmir, and Konya. The shaykh al-Islam was the head of the judicial administration as a whole; the qadi-askars (chief judges of the military) of the Balkans and Anatolia ranked next. Judges were seasoned by appointment up the ladder of positions. The judicial hierarchy and the teaching hierarchy were linked in that an appropriate level in the teaching system was a prerequisite to appointment to a judicial position. Qadis had considerable administrative importance; their duties not only included the judging of petitions but also inspection of the military, oversight of tax collection, supervision of the urban economy, and the application of government regulations in all domains of state interest. To get a job in this system, the student had to be sponsored by someone who held a high-ranking post. The student’s first position would as a repeater in a college. He would teach at a number of graded colleges, and eventually he could reach the level of a judgeship. The position of a mufti was not reached through a hierarchical gradation of “mufti-ships”; rather it was approached through the college professorships and judgeships.

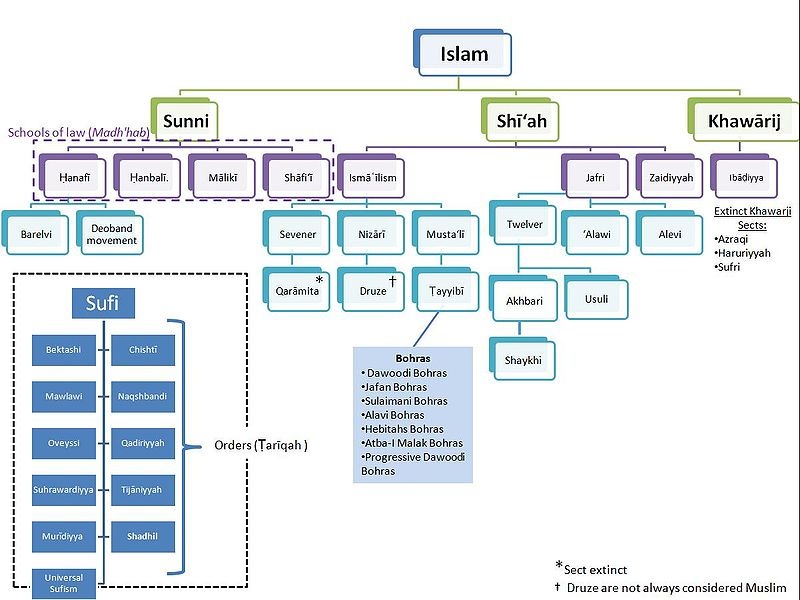

The Ottomans thus gained control over the ulama and made them functionaries of the state, and they also co-opted the leading Sufi brotherhoods. Sufi-led tribal rebellions were crushed during the fourteenth to the sixteenth centuries. The Bektashis became the patrons of the janissaries. Urban Sufis were provided in the time-honored manner with gifts, endowments, and a place in Ottoman court ceremony. The Mevlevi leaders had the ceremonial function of girding a new sultan upon his accession with a holy sword. The representatives of spiritual otherworldly power thus became the protectors of the state. In comparison with other Muslim societies this was an extraordinary organizational achievement, but it came at a high price. Insofar as the ulama and leading Sufis became functionaries of the state, they ceased to represent the mass of Muslim believers and could no longer protect the people from abuses of political power. To the extent that they were the servants of the state and the defenders of Ottoman legitimacy, they could not effectively resist corruption in the government. As much as they became a class of functionaries dependent on government offices and on offices for their children and students, they became a self-interested and powerful interest group within the state itself. By the eighteenth century a closed aristocracy of Ottoman ulama was in existence. The ulama were particularly favored because they had considerable opportunities to acquire properties through waqfs (endowments), and they were not threatened with confiscation of property after death. Ulama families lasted longer in power than any other element of the government elite, and a small group of families dominated the religious establishment. From 1703 to 1839, eleven Istanbul families accounted for twenty-nine of the fifty-eight shaykh al-Islams.

But as the bureaucracy became ossified, the protest movement of Kadizadeli developed. Named after Kadizade Mehmed (d. 1635; he was a preacher at the mosque of Aya Sofia), it was a puritanical movement to reform both the ulama and the general society. The movement was opposed to the consumption of coffee, tobacco, and opium; to singing, music, and dancing in Sufi ceremonies; and to pilgrimages to saints’ tombs; they denounced the writings of the thirteenth-century philosopher Ibn al-Arabi and called on good Muslims not only to lead moral lives but to force others to follow “the straight path.” The movement in many ways was implicitly anti-Ottoman, because the Ottomans had long tolerated religious variation in their empire and historically had parlayed religious spectacles into Ottoman legitimacy. The movement was only partially successful, however, because the dominant Istanbul families fought to keep control of the bureaucracy. Their reaction led to more conservative religious teaching and to the further consolidation of a small religious elite. Imperial support was always forthcoming because it seemed that this was essential to the stability of the empire. The religious elites, once recruited to sustain the regime, had thus become a self-perpetuating body.

The Ottoman State Apparatus And Religion

803 – 010

Home

Last Updated: 04/2022

See COPYRIGHT information below.