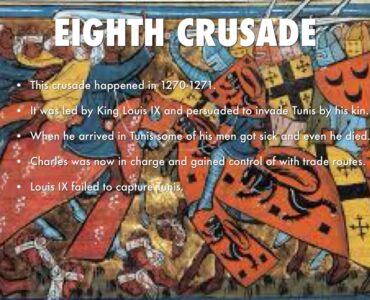

The Economy Of The Ottoman Empire:

Land, Urban Markets, And International Trade

The Ottoman empire was unusual among Middle Eastern empires in the degree to which it was able to bring the subject population under state control. Critical to this control was the regulation of the economy. The Ottomans operated on the principle that the subjects should serve the interests of the state, and the economy was organized to ensure the flow of tax revenues, goods in kind, and services needed by the government and the elites. The populace was systematically taxed; the Ottomans were the best record-keepers in Middle Eastern history. The tax base was exhaustively described in cadastral surveys that took stock of the population, households, property, and other resources. Ottoman economic policy on trade was based on a fiscalism that was aimed at accumulating as much bullion as possible in the state treasury, but at the same time balancing this with a concern for the general well-being of the Muslim population. The Ottomans did not see trade policy or scientific and technological development as a means of creating wealth. Rather, they still thought in terms of wealth derived from conquered and annexed territories.

Peasant lands were organized into family farm units; villages were not usually collectivities in possession of lands but rather agglomerations of independent peasant house}e were common interests, such as village meadows, threshing floors, water, and pasturage. For the Ottomans the productivity and the taxation of the land was the primary concern. In theory all lands were owned by the state (miri), but there were two subclassifications:

- Tapulu: lands that were on perpetual lease to peasants who had the right to the usu and to assign that right to their male descendants, and

- Mukatalu: lands that were leased to a tax collector in return for the payment of a fixed lease.

Incomes from state lands were also distributed in the form of timars and other stipends. The peasants were taxed by measuring the surface of the land, the size of the household, and the oxen available for labor, which was in effect a rough measure of productivity. This system of taxation (called the cifthane system) was appropriate to semiarid, dry farming devoted largely to wheat and barley, and it was derived from Roman and Byzantine precedents.

A study of north-central Anatolia in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries provides a deeper understanding of the workings of the land and tax systems. When the Ottomans obtained control of these regions in the mid-fifteenth century, they had to concede Turkish military rulers and Muslim religious leaders ownership rights to the land. In the course of the next century and a half the state struggled to dispossess the local notables and to reassign the tax rights to timar holders appointed by the central government. Still, much property remained mulk (private property) or waqfs (endowments), but these tended to be fragmented small holdings often in the possession of allies of the central government.

In the sixteenth century general population growth was stimulated by increased security and by the settlement of nomads. The regional economy grew enormously, with an expansion of peasant production of perhaps one hundred percent accompanied by considerable population growth. As surplus population moved to the towns, increased demand provided new markets for agricultural produce. Truck gardening, fruit growing, and viticulture expanded. Peasants produced ever more fruits, vegetables, and sheep, for which they had a cash market, though grain production for taxes and subsistence still dominated the rural economy.

The economy’s expansion took place by an increase of output from small peasant plots. Although the surplus was largely taken by officials and revenue collectors, this did not result in the dispossession or enserfment of peasants or their conversion to wage laborers on large holdings. Limited commercialization favored revenue holders but did not go so far as to disrupt the peasant economy. State protection of peasant interests also played a large role. The state protected the rights of peasants to the usufruct of the land, controlled the amounts of produce that could be taken in taxes, and set the rules for the marketing of the produce. The state thus protected the peasants against the rise of feudal authorities and kept a smallholding peasantry on the land.

The provisioning of Istanbul was a principle concern of Ottoman economic policy. The Ottomans did not use market mechanisms so much as requisitions to supply the court, the army, the administration, and the populace of Istanbul. Provincial merchants and officials were required to provide a steady stream of goods — grain, sheep, food products, leather, wood, metal, and other products — for direct imperial use or for sale on the Istanbul market. Ottoman workshops produced luxury products such as silk garments directly for the court. Ottoman regulations forbade the export of numerous products until the needs of the capital had been met. The Ottomans also regulated production through an extensive guild system that organized workers under the control of guild functionaries, market officials, and military authorities to ensure the production of goods of standard quality, at reasonable prices, for distribution to the state elites and to the population of the capital. The enormous size of Istanbul and its economic demands had a tremendous impact on the surrounding territories. Istanbul’s demand for grain turned the region from the Dnieper River to Varna (in modern-day east Bulgaria) into a commercial agriculture and livestock region. Along the Sea of Marmara (in northwest Turkey), villages produced wine, olives, and fruit for the Istanbul market. From Anatolia came sheep, hides, grain, and many other products.

Although the Ottoman economy was based primarily on agricultural and craft output and Ottoman policy was oriented toward the conquest and control of territory as the basic source of wealth, international trade was nevertheless of considerable importance. The Ottomans held a central place in world trade linking the Middle East and East Asia to Europe, and in the north-south trade from India and Arabia to central and eastern Europe. A great deal of Ottoman foreign policy, including its interventions in the Mediterranean, Central Asia, Yemen, Iraq, and the Indian Ocean, can be seen in terms of the importance of international trade. After the conquest of Constantinople, the first political task for the Ottomans was to wrest control of the Black Sea, the Aegean, and the eastern Mediterranean from the Venetians and the Genoese. The conquest of the Arab provinces and Egypt in 1517 gave the Ottomans control of the trade routes and the flow of resources through the Levant (the eastern shores of the Mediterranean between western Greece and Western Egypt), and positioned them to take over Mecca and Medina, Yemen, and southern Iraq and to fight the Portuguese for control of the Indian Ocean trade.

With these territories in Ottoman control, Bursa emerged as the principle entrepôt of the empire. Indian spices coming to Jidda (a port on the Red Sea) were caravanned to Mecca and then to Damascus, Aleppo, Konya, and Bursa. The sea route from Alexandria to Antalya (in southwestern Turkey) was also in use. Eastern goods from the Sudan, Egypt, Syria, and Arabia passed through Bursa on their way to Istanbul and to further destinations in eastern and central Europe. Edirne, Sarajevo, and Dubrovnik became important centers for the trade of the Balkans, the Adriatic, the Mediterranean, and Europe. On these routes the Ottomans exported silk, rhubarb, wax, pepper, drugs, fine cotton cloth, hides and furs, imported woolen cloth, metals, and money. Another route from Bursa to Istanbul to Akkerman (in southwestern Ukraine; renamed Belgorod-Dnestrovski in 1944) brought Ottoman and eastern goods into Poland and central Europe. This trade consisted of such local products as wheat, fish, and hides, and such oriental luxuries as paper, silk, and English, Florentine, and other fine woolen cloths. An alternative route from Bursa brought goods into Romania and Hungary. The Black Sea trade was equally lively. Important routes ran from Caffa to Kiev and to Moscow. Caffa gathered goods from the whole of the Black Sea region but also from Istanbul, the Aegean Sea region, and Europe. Slaves, including Slavs captured in war, sub-Saharan Africans, and captives taken from the steppes of inner Asia, were an important product in the international trade.

The Portuguese incursions into the Indian Ocean in the sixteenth century led to a major reorientation of world trade. Now eastern goods could be shipped around Africa to Lisbon, avoiding the Ottoman-controlled Middle East and the Venetian hold on luxury trade in the Mediterranean. Nonetheless, the Portuguese did not cut off the spice trade through Ottoman territories. The Ottomans maintained forces in both Yemen and Basra; they inaugurated cooperative ties with Gujarat (in Western India) and Aceh in Sumatra to keep alive both political resistance to the Portuguese and commercial contacts. Even Venice’s Levantine trade recovered in midcentury. By the late sixteenth century goods caravanned to Damascus or to Cairo were being picked up at Alexandria and Tripoli by Venetian ships. The British and the Dutch entered the struggle for control of the international spice trade and seized colonies in India and the East Indies as bases for an effort to monopolize the trade. By 1625 the north Atlantic sea powers finally cut off the spice trade to the Mediterranean. The Ottomans could still compensate by a lively trade in silk and coffee and in Indian cotton goods and dyes, but the most lucrative part of the trade was lost to the cape routes to western Europe. Moreover, from their controlling position in the Indian Ocean the British and the Dutch began to compete directly with Ottoman trade in the Mediterranean. In 1580 the British made their first trade treaty with the Ottomans and began to buy silk and sell cotton goods and metals to the Ottomans. Even spices began to come into the Mediterranean from Europe rather than directly from the Indian Ocean.

At the end of the sixteenth century, Izmir became the leading Ottoman port, gradually eclipsing both Bursa and Aleppo. As the Ottomans lost their grip on the Izmir region, French, Dutch, English, and Venetian merchants flocked to the area. Izmir became a cosmopolitan town, home to Arab camel caravaners and Armenian, Greek, Jewish, and Turkish merchants. The Europeans promoted a lively trade in cotton, wool, dried fruit, and grain, and built up a strong internal supply system. Trade through the Ottoman empire was t by the end of the sixteenth century. Ottoman janissaries, customs collectors, and other officials began to act as free agents and to evade the authority of Istanbul. Izmir’s links to Istanbul were cut as it was partially integrated into the European economy. The Ottomans were losing control of the Mediterranean trade to European merchants.

In other respects, too, the Ottoman empire was falling behind in international trade competition. The Atlantic economy and the growth of trade in such western staples as sugar, coffee, tobacco, and cotton had come to greatly overshadow the silk trade. Now the most lucrative trade was shifting from rare luxuries to goods for mass consumption, to the advantage of the Atlantic trading states. Europeans were gaining relative advantages in banking, insurance, and shipping profits, and with the beginnings of the industrial revolution they were in a position to sell high value-added manufactured goods and skilled services in return for raw or semi-processed raw materials.

Until the end of the sixteenth century the Ottoman empire was a self-contained trading system not dependent on the world economy. In the seventeenth century the Ottoman empire still retained a degree of commercial autonomy. Ottoman merchants were still able to build their own trading networks, accumulate capital, and dominate the trade in locally produced products, but by the mid-to-late eighteenth century European economic supremacy was assured, and the Ottoman empire became a dependent part of a European-dominated world trading economy.

The Economy Of The Ottoman Empire: Land, Urban Markets, And International Trade

803 – 008

Home