Crisis and Change in the Ottoman System: The Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries

For centuries the Ottoman ruling system was built up on the basis of the systematic rationalization of regional political, cultural, and historical precedents. Ottoman state power was grounded in a refinement of the Byzantine, Muslim, Seljuk, and Mongol precedents for regional power. By the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the era of construction was over and the Ottoman society was evolving in ways that were detrimental to the continuation of a dominant centralized state.

One critical factor in the deformation of Ottoman power was the decline of the central state. As the slave elites gained full control of the government and as religious functionaries were entrenched in a bureaucratic regime, they began to serve their own interests rather than the long-term interests of the sultan and the state. Janissaries demanded and received exemptions from the strict requirements of the slave system and were allowed to establish families, to work in the civilian economy, and eventually to remain on the state payroll without providing military service. Provincial officials squirmed out of central control and began to usurp local resources, competing with the capital for control of local economies, diverting the flow of requisitioned goods to Istanbul, converting tax farms into various types of quasi-private property, and building up local military support. As patronage relationships became ever more important throughout the seventeenth century, Ottoman officials at all levels created large households resembling the sultan’s household, households that served as a basis for patronage networks and the employment of large numbers of men. Prominent chieftains in pastoral regions rose in importance. Tax farmers had an opportunity to make themselves independent and to build political bases in the countryside. Though peasant landowning continued to be the most important form of tenure, large estates were being formed in the Black Sea region, Macedonia, Thessaly, and some parts of Anatolia, as it became increasingly lucrative to supply Istanbul and the European markets. Throughout the empire local notables — beys, pashas, and ayans — were taking power into their own hands.

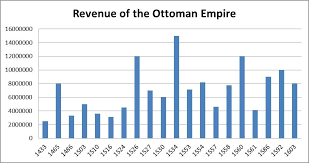

Economic changes beyond Ottoman control helped to undermine the centralized state. The discovery of the new world and the tremendous supplies of silver brought back to Europe from American mines undermined the price stability of the whole Mediterranean and unleashed an intense competition in the Ottoman empire for control of resources. European economic competition was winning away control of international trade. The competition from India and Italy, and later from Britain, was undermining Ottoman craft production. Raw materials grew more costly, but selling prices declined. Moreover, there were deep disturbances in the economy of the Anatolian heartlands. Ottoman security and prosperity was undermined at the end of the sixteenth century and in the seventeenth century by rising population, large increases in the number of unemployed, demobilized, and unsalaried soldiers, and vagabond students and bands of armed peasants roaming and ravaging the countryside. Provincial administrators and irregular soldiers fought against the government forces. Istanbul janissaries and local militias struggled for power in the provinces.

The Ottoman response was counterproductive. The treasury tried to reduce the expenditure on armed forces, which led to the further displacement of provincial soldiers, who then turned to brigandage. To reinforce central authority, the government had to station permanent garrisons, which then became identified with local economic interest groups that exploited their positions for their own benefit. These upheavals, collectively known as the celali rebellions, appear chaotic, but they had a deep political significance. As the central state weakened and as provincial officials and notables struggled to aggrandize their power, Anatolian Muslim subjects also fought to acquire the privileges reserved for the political elite. The celali rebellions then were not criminal or peasant protest movements; rather, they represented a political struggle of upwardly mobile peasants and small-town populations attempting to gain a share of the prerogatives of power.

From the Ottoman perspective, these changes were particularly ominous in the Balkans, where the tendencies toward decentralization of power and usurpation of lands, tax revenues, and supplies were exaggerated by the trade with Europe. The ready availability of export markets increased local incentives to evade Ottoman regulations and to develop local power by trading with Europe. Merchants who refused to ship fruits and grains directly to Istanbul but instead sold them to European merchants also imported muskets to defend their interests. As the de facto autonomy of the Balkan provinces increased, a new political philosophy began to take hold among Balkan intellectuals, merchants, landowners, traders, and others. Mainly Christians, less closely identified with the Ottomans than were the Muslims, Greeks, Serbs, Romanians, and others began to speak of their national identity and heritage and their right to independence from the Ottoman empire. The seeds that would undo the multi-religious, multiethnic Ottoman society in favor of modern national states were already sown.

The declining power of the central state was part and parcel of a disastrous series of military setbacks. The empire, which was still expanding in the sixteenth century and stable in the seventeenth, began to lose ground to its Russian and Habsburg opponents. The Habsburgs defeated the Ottoman attack on Vienna in 1683 and invaded Hungary and Serbia, and in 1696 the Russians took Azov and gained a foothold on the Black Sea. Although the Ottomans were able to counterattack in the early decades of the eighteenth century, by the later decades of that century they suffered staggering losses. In 1774 the Russians established their supremacy in the Crimea and Romania; by the Treaty of Jassy in 1792 they were in control of the Black Sea and in a position to threaten Istanbul. In 1798 the French emperor Napoleon invaded Egypt. These defeats were clear warnings that the Ottoman empire had fallen militarily as well as commercially behind its European competitors and that its territorial integrity, even its survival, had come into question.

In this crisis the empire was swept by proposals for reform and rejuvenation. Conservative critics called for a return to the policies of the great sultan Suleyman the Lawgiver; more radical critics called for the adoption of European technology, military organization, and administrative arrangements. Ottoman society was awash in a wave of European cultural fascination. European painting, rococo decoration, and tulip gardens were the rage. A celebration of personal sensibility and expressiveness overcame the Ottoman elites. Out of this cultural ferment, the Ottoman Empire would renew itself again in the nineteenth century.

Crisis and Change in the Ottoman System: The Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries

803 – 007

Home

Last Updated: 04/2022

See COPYRIGHT information below.