The Eastward Journey Of Muslim Kingship

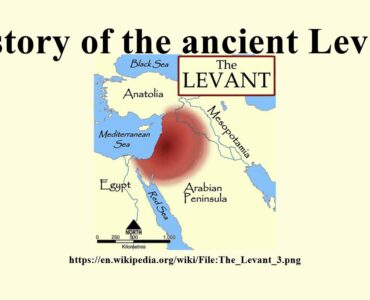

Islam is above all a pan-Asian religion. It shapes the beliefs and practices of millions of Asians, from Central to South to Southeast Asia. There are other pan-Asian religions — Hinduism to the far south, Buddhism to the Far East — but none that spans the southern rim of the Asian continent to the extent that Islam does.

But how did Islam become not only a religious marking but also a civilizational force from the Arabian Sea to the shores of the Pacific? That question cannot easily be answered. The emergence of distinctive social patterns in South Asia have parallels, though not equivalents, in Southeast Asia. Muslim invaders from the northeast brought with them (or developed after their arrival) traits that have since characterized the Islamic experience in South Asia for much of its known history. Centuries later, Muslim traders, coming from Arabia and India, began to settle in significant numbers in the archipelago known today as Southeast Asia. They also professed and pursued Islamic loyalty, but in different circumstances, with disparate outcomes.

Despite their conjunction in this chapter, the Muslim communities of South and Southeast Asia remain discrete and separate, both in the ideal norms they profess and in the day-to-day practices they pursue. Although it is difficult to link together two distant regions of Asia that have never known a fully shared history, the one symbolic marking that they share, Islam, justifies such an effort, especially in book that takes as its subject the entire spectrum of Islamic history.

The Mughal emperor Shah Jahan (r. 1628–66) considered himself the apogee of the dynasty that the great steppe conqueror Timur had founded 250 years earlier. Shah Jahan is depicted in this painting as the just emperor standing on a globe, and the roundels in the umbrella over his head give his genealogy back to Timur. The crucial marker of symbolic authority is the name Sahib Qiran “Lord of the Conjunction”, which confirms the authority of the sovereign through astrological proof of his predestined glory.

The Prehistory of Islamic South Asia

Certain patterns Of social mobility and civic organization typify South Asia from the Indo-Aryan period (1000 b.c.) on: a militarized society, with a standing army that requires regular use, often to invade and conquer adjacent regions; the autocratic rule of a military leader who is invested with instrumental power but who often claims divine authority and patronizes scholars to further that claim; and the existence of monuments that commemorate religious heroes and rulers of the past, built by military leaders to strike awe in their subjects. In this sense the prehistory of Islamic South Asia is not located in the life of Muslim societies further to the west; rather, this history is located in the reigns, or the imagined reigns and legacies, of the most illustrious kings of earlier dynasties. Two such figures stand out: Alexander the Great (356–323 b.c.e.) and Asoka the Munificent (r. 272–236 b.c.e). Together they projected Greek and Buddhist legacies into South Asia. Alexander was a brilliant soldier who wanted to be remembered as a wise king. Among the scholars he patronized was Aristotle. He represented the Achaemenid style of governance linked to the Persian emperors Cyrus and Darius. Asoka founded the Mauryan dynasty. He had no courtier to rival Aristotle, but through the monumental building inspired by his dramatic conversion to Buddhism he continued the style of royal patronage familiar from his Persian-Greek predecessors. Even though no literary texts survived, Asoka’s monuments did, and they were used and reused by successive dynasties, including the later Muslim monarchs of Central Asia.

Persian is the crucial element, and the thesis thus presented about Islam in South Asia accents Persian influence. Although Arabic and Turkish elements can be identified, they matter less than the Persian. Despite the fact that Islam is often identified with Arabic language and Arab norms, these merely provided the patina for Muslim expansion into the subcontinent. Although the Turks comprised the main source for Muslim armies, neither the Turkic language nor its cultural forms characterized the outlook of these newcomers to Hindustan (South Asia). Beyond the Arabic patina and the Turkic frame was the central image of this newly emerging social formation. The picture had its own design: Persianate.

Persianate is a new term, first coined by the world historian Marshall Hodgson. It depicts a cultural force that is linked to the Persian language and to self-identified Persians. But the term applies to more than either a language or a people; it highlights elements that Persians share with the Indo-Aryan rulers who preceded Muslims to the subcontinent. Two elements are paramount: hierarchy, which consists of top-down status markings that link all groups to each other in a clear order of rank that pervades all major social interactions; and deference, which requires rules of comportment toward those at the top of the status scale, especially the reigning monarch or emperor. The office of emperor first depended on military prowess, with defense of the realm, provision of public works, cultivation of land, collection of taxes, and dispensation of justice among his major administrative tasks. Equivalent to these functional aspects of his office, however, were the adornments of that office: magnificent palaces, expansive gardens, a lofty throne, and garments of unimagined splendor. In short, the emperor was the focal point of a court culture that included a range of specialists: architects and artists, craftsmen, musicians, poets, and scholars.

If this profile describes the totalitarian ideal of a hermetically sealed hierarchical system of governance, it omits several crucial elements that came to describe the kind of imperial rule exercised by the new Aryan elites — the Persianate Turks, who came to dominate North India from the tenth century on. Chief among these, as noted by Robert L. Canfield, were the use of the Persian language itself in a wide range of functions, administrative as well as literary, and the development of an expanding cultural elite that saw itself as expressing Persianate values, even when they were not fully allied with Islamic norms. This expansion and re-articulation of Indo-Aryan social values may be called either Persianate, to stress the importance of Persian as a linguistic component, or Islamicate, to acknowledge the way in which Islam was invoked even when the connection between cultural observance and religious loyalty was very slim. The two terms are so close that sometimes they can be used interchangeably. Crucial in each case is the expansion of connotative meaning to include more than linguistic usage (Persian) or religious commitment (Islamic).

The Eastward Journey Of Muslim Kingship

803 – 006

Home

Last Updated: 04/2022

See COPYRIGHT information below.