Concept Of Justice

This entry comprises two articles. The first discusses concepts of justice that inform Islamic political discourse and that, more broadly, suffuse the Islamic worldview; the second focuses on the notion of social justice in modern Islamic thought as developed in the writings of Sayyid Quṭb and others.

Concepts of Justice

It has been argued that if the Christian worldview is predominantly cast in terms of love, then the Islamic one is suffused by a discourse of justice. As one commentator has put it, “neither in the Qur’ān nor in the Traditions are there measures to indicate what are the constituent elements of justice or how justice can be realized on Earth” (Khadduri, 1984, pp. 10–11). However, the ideas of paying one’s moral and fiscal debts and of tempering retribution with mercy are features that characterize both God and the just person. For an individual to be ῾adl (just) is, as the term implies, to be balanced, to engage in acts that are framed by an awareness, born of the pursuit of reason over passion, of the harm that may be done to the ties that bind individuals to one another and all believers into a single community. The Qur’ān (6.152) thus enjoins one to “be just, even if it should be to a near kinsman” and demonstrates practical application when, for example, it recommends that contracts be written down in order to avoid subsequent doubt. It is, therefore, possible to see in the Qur’ān and Muḥammad’s own actions an implicit theory of justice that informs later interpretations and applications.

Central to the prophetic conception of justice are three features: relationships among men and toward God are reciprocal in nature, and justice exists where this reciprocity guides all interaction; justice is both a process and a result of equating otherwise dissimilar entities; and because relationships are highly contextual, justice is to be grasped through its multifarious enactments rather than as a single abstract principle.

Just individuals are those to whom power appropriately devolves, because they have regulated their ties with others according to balanced, reciprocal obligations. These reciprocal obligations reduce social chaos and facilitate ever‐greater networks of indebtedness among those who develop their God‐given reason to understand the divine word and the mundane world alike. Justice as the process of equating implies that reason and experience must be used to calculate similarities, a process that shows itself in qiyās (analogic reasoning), no less than in attending to the differences between men and women, Muslims and non‐Muslims, and assigning each category to its respective domain. The contextual quality of justice shows itself in the quest for an understanding of the spheres within which each person or historical moment exists and the ways in which fundamental qualities and kaleidoscopic changes must be scrutinized and balanced.

The elements of Islamic justice were the source of contention among moral and political theorists from the outset of Islam. During his lifetime the Prophet governed in direct accord with divine precept. After his death disagreement centered on which line possessed the capacity to rule justly and which procedures for rule should hold sway. For Sunnīs political justice lay in acknowledging legitimate authority through ijmā῾ (community consensus); for the Shī῾ī it lay in the strict perpetuation of the line of legitimate succession. For the Sunnī the ruler’s legitimacy was in theory hedged by the need for shūrā (consultation). The Sunnī Umayyad dynasty, however, combined the doctrine of an elected caliph with the idea that the responsible believer is the one who does not fail to obey the legitimate successor to the Prophet. Others, known collectively as Qādirīyah, believed that each man is responsible for his own acts and that political justice lies not in compulsory obedience but in holding even the caliph responsible for his unjust acts.

Notwithstanding its claims for continuity, the model of the caliphate failed to provide specific guidance for a theory of the just sovereign. During the brief period in the eighth century when the ῾Abbāsid dynasty favored them, the Mu῾tazilah argued that divine justice is beyond human grasp but that human reason can best approximate divine justice through the exercise of reason and free will. Indeed, they argued, it is by such acts that one gains unity with that inner sense of justice toward which all men are naturally directed. Although the Mu῾tazilī emphasis on reason and unity brought them into conflict with more powerful opponents, the terms of the debate were set: to the legalists (including the later systematizer al‐Shāfi῾ī [767–820]) men choose to do justice or injustice through their adherence to the law; to al‐Ash῾arī (d. 935 or 936) men could do justice but could not create its very terms; to al‐Ṭaḥāwī (d. 933) and al‐Bāqillānī (d. 1012) the very uses to which God’s created justice are put are themselves creative acts. By contrast, the Shī῾ī theorists of the Būyid and Fāṭimid dynasties of the tenth and eleventh centuries argued that, in the absence of an infallibly sinless imam, men may even defend themselves through taqīyah (dissimulation) against an unjust caliph—a practice that Sunnīs regarded as little more than personal convenience. To both of these positions Ṣūfī theorists, such as Ibn al‐῾Arabī (1165–1240), countered that justice can be made manifest in this world not by creative acts of reason but only by engagement in ecstatic devotion.

As Islam spread into new territories and as contact with classical Western thought increased, Islamic thinkers had to consider the practical applications of justice in law and politics. The Virtuous City of al‐Fārābī (c. 878–c. 950) was to be characterized by the division and protection of all good things among the people; the Just City of Ibn Sīnā, (980–1037) was constituted by a social contract among administrators, artisans, and guardians, the welfare of all being secured by a common fund of resources. As the demands of actual administration increased, specific content for these propositions developed. The concept of maṣlaḥah (public interest), as elaborated by al‐Ghazālī (1058–1111) and al‐Tawfī (d. 1316), received legal force by calculating social consequence against individual interest; procedural justice lay in the qualities of the judge’s character, in the use of a council of adviser/assessors, in the use of advisory opinions by outside scholars, and in the increasing use of elaborate procedures for ascertaining the credibility of witnesses. The traditional absence of appellate structures reduced dependence on any fallible judge, although the accepted legitimacy of different schools of Islamic law and resident experts allowed local custom to inform the practice of daily justice.

Because justice was seen to pervade all domains of life, Islamic thinkers sought to unify political, legal, and social justice. In the face of Mongol invaders and Western crusaders, Ibn Taymīyah (1263–1328) sought to stem the decline of Islam by urging that despotic rulers must give way to a politicized sharī῾ah (the divine law) in which, for example, precedence would be given to family unity over emotion‐laden repudiation, and just wars would be limited to defensive actions. From his initial emphasis on society as a fluctuating balance of religion and ῾aṣabīyah (social solidarity), Ibn Khaldūn (1332–1406), observing the decadence of fourteenth‐century Egypt, increasingly stressed procedural regularities and ta῾zīr (discretionary penalties) as a check on political injustice. Although he and others believed men were inherently unjust, their more secular political approach to issues of justice had to wait until later ages to achieve a more activist orientation.

The intrusion of Western colonialists, particularly in the nineteenth century, prompted two major strands of thought on the question of justice. Modernists sought to include institutions modeled after those of the West into their political systems, although traditionalists found Western approaches inconsistent with Islam. Jamāl al‐Dīn al‐Afghānī (1838–1897) believed that the injustices of Muslim despots could be rectified by renewing the principle of consultation in the form of elective assemblies and by the political unity of all Muslims against Western powers. Like his predecessors he combined moral renewal through revitalized virtues with a political program that would insure fuller community participation. But when al‐Afghānī’s proposals failed to move Muslim tyrants or the populace at large, some, like his student Muḥammad ῾Abduh (1849–1905), looked to Western procedural standards, which they did not regard as incompatible with Islam, for guidance. As a judge and grand muftī, ῾Abduh issued fatwās allowing, for example, the use of interest through postal bank accounts. He often spoke in terms of revelation and natural law as well as in terms of the compatibility of revelation with evolution and social reformation, but his equivocation and his deep concern with the moral transformation of society signaled precisely the dilemma faced by many of his era who were drawn to both Western and indigenous forms of injustice.

Many of the conflicts between modernists and traditionalists centered on the adoption of new legal codes. The very idea of a code was largely a Western one, but the process of codification forced many Muslims to consider which propositions they regarded as essential to Islam and which as dispensable accretions. Moreover, the process of adopting codes offered the opportunity for establishing a system for legal changes. Of central importance was the formulation of the Mecelle (Ar., Majallah; Civil Code), which was applied throughout Ottoman territories in the 1870s. Together with the short‐lived Ottoman constitution of 1876, it marked the trend that culminated in Turkey’s unilateral disestablishment of Islam and its wholesale adoption of European codes. By contrast French colonial territories adopted French commercial and criminal law, but these countries retained relatively intact their Islamic family law practices until they achieved national independence.

Owing largely to the efforts in the late 1940s of the Egyptian jurist ῾Abd al‐Razzāq al‐Sanhūrī (1895–1971), civil codes were drawn up for Egypt, Iraq, and Kuwait, with other countries drawing on elements of his work. In each instance the codes left it to sharī῾ah principles to fill in where the code was silent. In fact, more often than not Western substantive law filled in the whole of the civil law, and the sense of distinctive Islamic principles—of fault and liability, of intentionality in contracts or unconscionable agreements— was largely replaced by non‐Muslim concepts.

By contrast, the strain between Western Islamic standards of justice has been most significantly tested in family law. Following independence in 1956, Tunisia took the more extreme position, formally abolishing polygamy and requiring all divorces to be pronounced by the judge. At the other extreme, Pakistan and the Gulf States continued highly traditional forms of Muslim family law, largely unaffected by outside forces. In between lay a vast array of compromises: from Morocco, where the code remains very close to Mālikī principles but places increased discretion in the hands of the qāḋī (judge), to Malaysia, where ῾ādāt (local custom) grants wives a share of all marital assets at the time of divorce. [See Family Law.]

The struggles over appropriate laws of personal status have profoundly affected views of the nature of Islamic justice: as women became more educated and occupied a greater role in the economy, justice was conceived by many as requiring greater equalization, though not full equality, of men and women. At the same time the very forces that led to such liberalization contributed to the backlash against it: fundamentalists, from Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini in Iran to the Muslim Brothers in Egypt, find the relations of men and women one of the domains where Western influence has distorted justice by rendering an imbalance among what they see as natural differences.

Similarly, in the criminal law the precepts of divine revelation have been read to imply ḥudūd (invariant punishments) for listed offenses and ta῾zīr (discretionary punishments) for a broader range of infractions. Some of these penalties, though rarely applied, conflict with international human rights conventions, while others bespeak localized standards of justice—as when, for example, a learned man may be held to a higher standard of behavior than an unlettered one, because his acts are thought to have greater consequences for society. Recent attempts by the ministers of justice of Islamic nations to compose a uniform penal law has yielded a document none is likely to adopt, because each nation adheres to quite different standards of punishment. The very process of drawing up such a document reveals both the commonalities and the discrepancies wrought by different histories and attitudes.

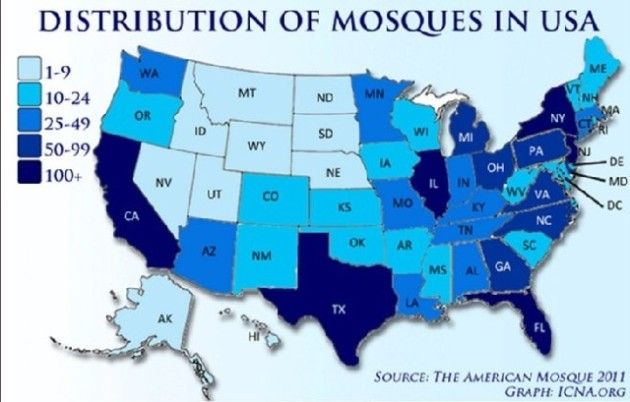

Issues of social justice have also taken very different paths. Although the language of distributive justice is broadly shared, neither modernists nor traditionalists have succeeded in capturing its terms for any universally accepted program. The combination of Islam and socialism in Algeria and Libya, for example, has resulted in the greater use of the central government for the redistribution of resources; moderate states, such as Indonesia and Jordan, have used public funds to reconstruct the educational system and provide greater security against disaster. But again, what is seen to be just depends far more on the political and economic circumstances of each country than uniformly adopted beliefs about Islamic justice. In this respect the intellectual history of the concept of justice replicates much of earlier history, for it is the local amalgam, proffered as distinctly Islamic, that both unites and separates Muslim nations.

One common concern is the nature of economic justice, exemplified by the permissibility of charging interest. Ribā, which is usually translated as “usury” but more accurately refers to any form of unjust enrichment, was historically avoided by various legal fictions. The rise of Islamic banking, however, has resulted in practices that are commensurate with modern economic institutions but are felt to conform to the prohibition on interest. This development is particularly important, because it is rare for Islamic conceptions of justice to be embraced in specific institutional enactments.

As fundamentalist regimes have taken power in Iran, Sudan, and several Malaysian states—and as their influence expands in Pakistan, Algeria, and Jordan—the equation of sharī῾ah with justice has been no more fully consummated than at other times in Muslim history. Although formally preeminent, Islamic law is not, in fact, given unalloyed application in any of the Islamic republics. Moreover, justice—in the sense of receiving a fair share of the wealth of the state—has led to an emphasis on delivery of actual services rather than the imposition of formal law alone. Thus the terms of justice have been put into play once again, and the quest for new equivalences, contexts, and forms of reciprocal obligation have become embroiled in bureaucratic and party structures.

If justice is central to the way that Muslims think of themselves, it must also be noted that jawr (injustice) plays no less a role. Injustice is often felt rather than articulated, and Muslims tend to believe, like Montaigne, that institutions, far from eradicating injustice, often provide a forum for its elaboration. Justice, for most Muslims, can only be expected where face‐to‐face constraints allow reciprocity to work, whereas the state is seen as unreciprocity incarnate. Where international actions or local corruption lead to a felt sense of imbalance, the personal offense that is taken is profound. Justice, to Muslims, is not, as Adam Smith had it for the West, the least of the virtues, because it is one that merely entails the avoidance of harm. Rather, justice is the most essential, if indeterminate, of virtues for Muslims, because it keeps open the quest for equivalence, a quest seen as central to both human nature and revealed orderliness in the world of reason and passion.

Justice

The most common referent for “justice” in Arabic, with a semantic field covering the concepts of “balance,” “mean,” “straightness,” “fairness,” “equal” and “equity,” are words derived from the root ʿ-d-l, usually ʿadl, but also ʿadāla, particularly in modern usage. Inṣāf, often glossed as justice, equity, or fairness, is semantically related to “half,” “middle,” or “medium.” Qisṭ, more often used along the lines of “equity” in distribution, is related to the concepts of “share,” “part,” “allotment,” or “measure.” Finally, ḥaqq covers a semantic field that includes concepts of “right,” “truth,” and “correctness.”

Justice In The Qurʾān

The Qurʾān mostly makes use of words derived from ʿ-d-l and q-s-ṭ—twenty-eight and twenty-five times, respectively. Most references to a morally substantive value of “justice” use these roots. The well-known verse (4:3) that establishes the permissibility of polygamy, for example, uses them as near synonyms:

“And if you have reason to fear that you might not act equitably (tuqsiṭū) towards orphans, then marry from among [other] women such as are lawful to you—[even] two, or three, or four: but if you have reason to fear that you might not be able to treat them with equal fairness (taʿdilū), then [only] one—or [from among] those whom you rightfully possess. This will make it more likely that you will not deviate from the right course.”

By and large, as in the above verse, the Qurʾān refers to “justice” in ways that presume knowledge of the substantive obligations of justice, directing believers instead to the obligatoriness and importance of acting in accordance with them: “Whenever you judge between people, judge with justice (bi-l-ʿadl)” (4:58); “Be ever steadfast in your devotion to God, bearing witness to the truth in all equity (bi-l-qisṭ); and never let hatred of anyone lead you into the sin of deviating from justice (a-lā taʿdilū)” (5:8); “Behold, God enjoins justice (ʿadl), and the doing of good, and generosity towards [one’s] fellow-men” (16:90); “Verily, God loves those who act equitably (al-muqsiṭīn)!” (49:9).

The justice that humans are enjoined to uphold in the Qurʾān is characterized in both intuitive and revealed terms. Morality and justice are often referred to as “that which is known” (maʿrūf) and immorality as “that which is denied” (munkar). One need not accept a rationalist or naturalist interpretation of Islamic ethics to accept the idea that the Qurʾān expects certain basic understandings of justice and morality to be widely known and valued. “Justice” is first about acting and judging impartially with no morally irrelevant characteristics such as kinship or wealth serving as the basis for advantage. As in all universalist conceptions of justice which reject the idea of justice as “helping friends and harming enemies,” the obligations of justice are both distinct from and have priority over one’s personal affective attachments and obligations to particular persons. As seen above, the Qurʾān warns against letting “your hatred of a people cause you to act unjustly” and counsels “when you voice an opinion, be just (fa-ʿdilū), even though it be [against] one near of kin” (6:152).

Here one can discern a fundamental connection to the idea of “equality (of value)” or “equal measure” in the concept of ʿadl. Unbelievers are thrice blamed for “making equivalence” (yaʿdilūna) between God and others (6:1, 6:150, 27:60); and the idea of ʿadl as one’s “ransom” on the Day of Judgment for one’s earthly sins (2:48, 2:123, 6:70) suggests the idea of an equal or equivalent exchange (of which, of course, there is none). For example, the Qurʾān exhorts, “kill no game while you are in the state of pilgrimage. And whoever of you kills it intentionally, [shall make] amends in cattle equivalent to what he has killed…or else he may atone for his sin by feeding the needy, or by the equivalent thereof in fasting (ʿadlu dhālika ṣiyāman)” (5:95). At the same time, an intriguing Qurʾānic passage refers to God’s creation of man’s nature “in just proportions (fa-ʿadalaka)” (82:8).

But if humans are expected to have some intuitive conception of justice as equity, fairness, balance, and impartiality, justice in the Qurʾān is ultimately about enacting God’s revealed and commanded positive rules. Another verse, which also elides the difference between q-s-ṭ and ʿ-d-l, exemplifies this:

“O you who have attained to faith! Be ever steadfast in upholding equity (qisṭ), bearing witness to the truth for the sake of God, even though it be against your own selves or your parents and kinsfolk. Whether the person concerned be rich or poor, God takes precedence over [the claims of] either of them. Do not, then, follow your own desires, lest you swerve from justice (taʿdilū): for if you distort [the truth], behold, God is indeed aware of all that you do! (4:135)”

Thus what it means to apply justice in defiance of personal ties or preference for the powerful is to uphold “God’s precedence,” meaning the rules God has laid down and the claims he has made for himself.

Justice is also known by its negation. The opposite of justice in the Qurʾān is expressed primarily as ẓulm or jawr. There are hundreds of Qurʾānic references to words derived from the root ẓ-l-m. Many of them are used in connection with God, and it is thus to the question of God’s justice that we now turn.

Divine Justice

One of the earliest and most enduring theological and dogmatic controversies in Islam related to God’s justice. A significant number of Qurʾānic verses make reference to God not acting unjustly towards his creatures (e.g., 4:40, 18:49.) However, a perennial theological question plagues the idea of God’s justice, namely, is it an expression of his wisdom and perfection, or rather his unconstrained will and power?

The Muʿtazilite school of theology pointed to the above verses to support their rational arguments in defense of the former view. Along with his oneness (tawḥīd), the idea of God’s justice was the core principle of Muʿtazilite theology—thus their moniker for themselves, “the people of divine unity and justice” (ahl al-tawḥīd wa-l-ʿadl). For the Muʿtazilites, justice is a quality that corresponds to the perfection of God. God must be just and equitable in his judgments, may not be unjust or arbitrary, and must always do what is optimal (aṣlaḥ) for his creation. More controversially, his acts cannot be incompatible with universal criteria accessible to reason for distinguishing good from evil. What makes determinations of good and evil accessible to reason is that certain actions are in themselves good or evil; good and evil are essences that inhere in certain acts. For example, on this view it is irrational to deny that lying is bad (qabīḥ) by essence and that justice is good (ḥasan) by essence, and not merely by convention, command, or consequence.

The Muʿtazilite view thus required an affirmation of the freedom of the human will or ikhtiyār (“choice”). For if God is just, and does not wrong his servants, then his punishments and rewards on the Day of Judgment must be in response to actions for which humans are themselves responsible. To punish humans for disbelief or acts of sin that God himself has caused and constrained humans to perform is tantamount to injustice and tyranny, traits that are a priori reasoned to be excluded from God’s essence. Man is thus the creator, author, and agent of his actions, and all evil and injustice in the world must be attributable to humans, not to God.

However, these views were found by early Muslim theologians to be in tension with certain Qurʾānic statements that God has created everything on earth and all motions in the universe. They also introduce the possibility that rational and revelatory accounts of justice might be in conflict, thus raising the question of which is to be accorded priority and authority. Despite the frequent assertion that any apparent contradictions between reason and revelation were only that—apparent and not real—the troubling nature of the mere possibility of these tensions led many theologians to accord a primacy not to God’s everlasting wisdom and reason, but to his will and power.

In response, the Ashʿarite school of theology tended to assert the following points of doctrine: God is radically free to create and command moral values; the content of justice is determined by what he has set out as the law in revelation; human destiny is predetermined by God; and human acts are caused by God. As to the ontology of justice, the important point is that acts (lying, killing, praying) do not have essences in which their justness or badness inheres, but are given a moral value only by God’s sovereign determination. In the words of al-Juwaynī (d. 478/1085): “The intellect does not ascertain the goodness of a thing or its badness. Something being good or bad falls solely within the disposition of the law…. What is meant by ‘obligatory’ refers merely to the act which, because the law commands it, is obligatory.” On the question of whether God can be regarded as the author of evil and injustice, which the Muʿtazilites found ludicrous, al-Ashʿarī (d. 324/935) insisted that God was indeed the author of human injustice in the world, but he distinguished between his willing injustice on his own part, unmediated, and willing injustice men do to one another.

While this solved the problem of how to consistently uphold God’s power, it raised other awkward questions about just deserts and human agency. Sunnīs writing within the Ashʿarite and Māturidī traditions thus articulated the doctrine of acquisition (kasb). This doctrine held that while God does in fact create all human actions in an ultimate sense, there is space for humans to “acquire” a certain measure of authorship and agency over their deeds. This was a way of theorizing both divine power over the world and human moral responsibility for those acts that God has already created.

Muʿtazilite views about God’s justice and human free will survived in both the Twelver and Zaydī Shīʿī traditions. The tenth-century Twelver creed of Ibn Bābawayh asserted that God is just (“He requites a good act with a good act and an evil act with an evil act”) but also “treats us with something better, namely, grace (tafaḍḍul).” He also recorded the doctrine that “human actions are created in the sense that God possesses foreknowledge and not in the sense that God compels man to act in a particular manner.” The attractiveness of these Muʿtazilite doctrines for the Twelvers and the Zaydīs may have had socio-political origins as much as intellectual or spiritual ones. With Ashʿarism ascendant under ʿAbbāsid rule by the late ninth century, there may have been an elective affinity between disaffected Muʿtazilites and oppositional sects. Muʿtazilite doctrines of justice, responsibility, and free will also hold a clear appeal for parties in opposition as they deny that might reflects right and discourage the oppressed from accepting existing realities on fatalist grounds.

The argument for God’s justice reached an intellectual apex in the works of falsafa, particular those of Ibn Rushd (d. 595/1198). In al-Kashf ʿan manāhij al-adilla fī ʿaqāʾid al-milla (Exposition of the Methods of Argumentation in Religious Doctrines) he writes that the Ashʿarite position that justice is only that which is commanded by the law and there is nothing just or unjust in itself, “is not only not the one proposed by revelation, but opposed to it” and “of the utmost absurdity.” Intriguingly and more than a little provocatively, he historicizes and relativizes the Ashʿarite doctrine by conjecturing that Ashʿarites needed to assert their doctrine that God created both good and evil in the world since “they needed to explain that God is described as just and the creator of all things, both good and evil, because in the past many nations believed erroneously that there are two gods, one creating good and the other creating evil. Accordingly, they asserted that God is the creator of both.”

Ibn Rushd’s own treatment of God’s justice focuses on the knotty question of why God willed that there be unbelievers in the world, since “if God had so willed, He surely would have gathered them all under his guidance” (6:35). As will be recalled, this was the basis for one of the arguments advanced by the Muʿtazilites for human free will: since God is just, it is unthinkable that he has damned certain people to eternal torment through no fault of their own; therefore, humans must have free will to believe or disbelieve, and act justly or act sinfully, thus meriting their recompense in the hereafter.

Ibn Rushd concedes that God has “allowed for the existence of some misguided people among the different kinds of existing entities, people who are predisposed to error by their very natures and driven to it by what surrounds them of misleading causes, whether internal or external.” His response, however, is to emphasize less the problem of God’s justice qua judge as his wisdom qua creator. God’s choice was either not to create humanity at all, or to create humanity with the stipulation that among humanity will be some who are wicked and who disbelieve. Thus the just action was to advance the greater good (the creation of humanity) rather than abstain from this creation in order to avoid a small amount of evil.

For all of the appeal of the ideas that God’s judgments are somehow substantively and objectively just and that humans deserve their treatment in the hereafter as a result of their freely chosen actions in this world, it was the view of God as defined by power and will first that prevailed in Muslim theological and juridical circles. Even those (Muʿtazilites or Muʿtazilite-sympathizers) who were inclined on principle to believe that certain actions are inherently good or evil and that God’s revelation merely reflects this did not necessarily deny that human behavior in this world should be judged according to the standards of the law as revealed by God. Thus it was primarily through the discourse of discovering the law that the substantive requirements of justice were articulated.

Legal Justice

In his famous Risāla, al-Shāfiʿī (d. 204/820) defined justice simply as “acting in obedience to God.” Thus the primary approach to the study of punitive, contractual, and distributive justice in Islam is simply to study the rules of Islamic fiqh in these areas. Short of outlining the specific rules of justice in individual areas of the law—translations into English exist of a number of canonical legal manuals—it is possible to note a few general aspects of Islamic legal thought that indicate assumptions about the content of legal justice.

The publicity of the law’s justification and articulation is such an aspect. Ideally, all claims to moral and legal knowledge are justified publically to a community of equals through agreed-upon methods of proof and argumentation. This alone represents a commitment to justice between moral equals not present in moral theories where political and moral obligations can be worked out in an insular fashion by elites or experts with no obligation to publically present and justify those obligations in the same terms as they were arrived at by the insular community.

“The core features of Islam’s publicity are the claim that (a) humans may justify impositions and obligations on one another as religious obligations only on the basis of proof from texts shown to be authentically from God; (b) the meaning of these texts is linguistically accessible to humans and their legislative force can in principle be apprehended through the application of certain interpretive methods; and (c) it is understood and publicly acknowledged that scholars do not have conclusive knowledge of the divine legislative ruling (ḥukm) on specific acts, and thus the scholarly community may not arbitrarily censor opinions arrived at through interpretive methods or close off scholarly inquiry. Indeed, Sunnī Islam’s commitments to universal public justification go even deeper than this, to the idea that rational proofs of both God’s existence and the veracity of Muḥammad’s prophecy must be provided to those subject to its ordinances.

A further commitment is to the universality of the law. In principle, there is one law for all believers. Rulers, scholars, and notables are all subject to it. “Law” is not a “noble lie” for the masses with opt-out clauses for statesmen, philosophers, gentlemen, or, importantly, mystics. However, while the scholars were able to monopolize (more or less) religious epistemic authority, they were not (until Khomeini’s doctrine of wilāyat al-faqīh) in charge of the state. They were thus often in the position of justifying certain departures from the ideal. Some of these efforts are noteworthy for their egalitarian and justificatory commitments.

For example, is it permissible to apply discretionary punishment (taʿzīr) differentially to social notables as opposed to the masses (the jurists held that there were no exceptions in the application of the mandatory ḥudūd punishments)? The idea seems deeply un-Islamic. Wealth, power, and social standing are not marks of virtue and do not privilege their possessors morally. In reality the elite always have special access to the halls of justice. Consider the eleventh-century jurist al-Māwardī’s exposition of this problem: “The censure due to people of dignity and honor is milder than that given to the contemptible or the impudent.” The justification for gradations of discretionary punishment (viz., ignoring, reprimand, vituperation, detainment, beating) is that the same goals can be achieved (“reform and rebuke”) with different people through different means. People of honor are deterred by public shunning or reprimand, while the base require detainment or beating. There are elements of social stratification creeping into the law (not to mention culture), but even here the jurists feel the burden of public justification.

Raising the subject of substantive inequalities within a law that proclaims equality and universality immediately invokes the three main classes of persons excluded from social equality: women, slaves, and non-Muslims. Non-Muslims are obviously expressly excluded from the justificatory community, although this does not preclude moral and legal obligations to them as prescribed by the law. Slavery and the social inequality of women are institutions that appear in the revealed texts. For Muslim jurists, treating slaves and women according to different rules is not in itself a violation of Islamic justificatory commitments as the theologians and jurists understood them, for these were not social customs or arbitrary preferences but textually redeemable practices. More than women, slaves—like non-Muslims—were excluded from the justificatory community, although slaves could convert and acquire their freedom, thus erasing any legally and religiously justifiable social distinction. Women, on the other hand, as Muslims were from the beginning part of the justificatory community; fidelity to divine sovereignty would require of them no less than of men that they accept the results of the investigation into the revealed texts.

Legal values of procedural fairness and impartiality are often expressed as requirements of judges. Legal manuals (as, e.g., Ibn Naqīb’s ʿUmdat al-sālik) command judges to treat both litigants with equal impartiality (yusāwī baynahumā), seating them in places of equal honor and attending to them equally. Judges are “to be stern without harshness, and flexible without weakness” and not to decide cases when their temperament or mood might affect the decision. They are to sit with “tranquility and gravity” and consult both credible witnesses and learned scholars. Judges may not accept gifts or decide cases involving relatives or business partners. Further requirements of procedure, evidence, and testimony are outlined in the manuals in order to advance fairness and impartiality.

Within the context of legal justice, it must also be noted that “justice” is also a personal quality of persons. The Qurʾān (5:95, 5:106, 65:2) speaks of the need for witnesses or scribes present during important transactions to be possessed of ʿadl. This quality, which the juridical tradition would eventually include as a necessary legal condition for those who discharge the obligations of witnesses, judges, market inspectors, and rulers, refers to an individual’s moral probity in a wide, but not impossibly demanding, sense.

In principle it is the jurists’ task to develop the particular rulings of the law so as to anticipate as many possible areas of its application and to ensure that it is thus both predictable and depersonalized; in this way the legal scholars also summarized basic legal principles to make maxims of law (qawāʿid fiqhiyya) to assist in the adjudication and application of the law. These maxims are often procedural or coordinative, but just as often contain substantive (if rather generic) statements about the requirements of justice. Some of the best known and important for the study of justice are: “A matter is determined according to intention”; “Injury cannot exist from time immemorial”; “Latitude should be afforded in the case of difficulty”; “An injury cannot be removed by the commission of a similar injury”; and “Necessity does not invalidate the right of another.”

Political Justice

The question of political justice raises a number of distinct questions. Most important among them are what the characteristics of a just ruler are, what claims of justice the subjects of political power have, and whether there are any limits to obeying an unjust ruler or regime.

Rulers are exhorted to be just in all genres of Islamic theological, legal, and political writing. In the earliest period of Islam, the ruler’s justice was to a large extent the function of his legitimacy. A just ruler was one who came to power through the approved procedure, whether by appointment by a predecessor, by “election” on the part of the “people who loose and bind,” or through inheritance via a designated line of descent. The first two conditions were variations on the conception of legitimacy that came to constitute Sunnism, whereas the last is the defining characteristic of Twelver Shiism.

Once in office, what makes a legitimate ruler just or unjust? The simplest answer is that a just ruler is one who applies God’s law, either directly or by appointing and then getting out of the way of judges. As noted in the previous section, the substantive content of justice to be executed by rulers and scholars is elaborated in the manuals and compendia of fiqh. However, treatises on the rules of governance (al-aḥkām al-sulṭāniyya) cover the most important duties made obligatory on the ruler within the Sharīʿah (his sharʿī duties), namely, the public legal validation of the Muslim community (umma), the validation of public worship, the execution of ḥudūd punishments, the waging of both defensive and expansionary jihād, the commanding of right and forbidding of wrong, the preservation of religion, and the collection of Sharīʿah-prescribed taxes.

But Islamic legal and political writing anticipates a space for the ruler to act at his own discretion, what might today be referred to as public policy, and here his justice is a measure of his own qualities and deeds. Rulers were expected to uphold and advance the welfare of their subjects, not to tax them beyond reasonable limits, to apply the law impartially, to listen to grievances (maẓālim), and to engage in consultation (shūrā) with important representatives of one’s community. Jurists sometimes also speak about the ruler’s duties beyond those prescribed by the Sharīʿah (his non-sharʿī duties): to use public power to protect internal security, improve infrastructure (roads, bridges, inns, walls, mosques, etc.), promote charity and social welfare, provide public medical services, and sponsor religious education. Many of these were provided by non-ruling notables and others in addition to the “state.”

Interestingly, and in this latter vein, justice is not always assumed to be coterminous with Islam. Naturally, the purest and most comprehensive standard of justice is that set out within the Sharīʿah. But for some scholars it is consistent to describe a ruler or a regime as believing-and-unjust or as unbelieving-yet-just. The locus classicus for this sentiment is found in Ibn Taymiyya’s (d. 728/1328) work on the ḥisba, the purview of the market inspector-cum-morals police, wherein he elaborated much of his political theory. In this treatise, the great Ḥanbalī theologian and jurist writes, “God preserves the just state even if it is unbelieving and does not preserve the oppressive state even if it is Muslim. It is said that the world persists with justice and unbelief and does not persist with oppression and Islam…. This is because justice is the order of all things. Thus if the affairs of the world are arranged with justice, then they are upheld even if the one responsible has no share of the hereafter.” While Ibn Taymiyya does not elaborate in any detail what conditions an unbelieving state must fulfill to be regarded as just, such a statement can only be read to comprise a certain kind of universal understanding of political justice that involves the rule of law, limitations on arbitrary power, and public coercion allowed only in the service of public goods and interests rather than the private interests of those in power.

If the subjects of political power have a right to expect the performance of these duties, do they have a right to demand them? The standard response within Sunnī thought is that while the ruler has an obligation to be just and is exhorted to fear God while exercising power, obedience to an unjust ruler is an absolute requirement of the ruled. Sunnism, after all, emerged out of the desire to maintain communal unity and prevent both the wanton bloodshed and religious schism that arose out of rebellion to political rulers in the early years of Islam. Fitna—sedition, chaos, civil strife—became the supreme political evil within Sunnism. An oft-invoked expression proclaims that a terrifyingly long period of time (thirty years, one hundred years) under an unjust ruler is preferable to a single day of fitna.

This stern conception of political obligation did not rise to the level of that demanded by the “divine right of kings” doctrine of medieval and early modern Europe or by Hobbesian social contract theory. Indeed, a contrary principle proclaims that “there is no obedience to a creature in disobedience to the Creator.” But this did not authorize the anarchy of a private right of veto on the part of any individual Muslim against any act of public power deemed impious. Furthermore, treatises on the rules of governance (al-aḥkām al-sulṭāniyya), later often styled as treatments of “religiously legitimate governance” (al-siyāsa al-sharʿiyya), anticipate and authorize the ruler acting according to his own judgment, both beyond the letter of Sharīʿah and also at times in opposition to it.

The right to disobey tended to be limited to egregious cases of a ruler’s interference in purely religious matters (of creed or worship) or, in the extreme case, if he abandoned Islam and sought to undermine it within his area of rule. It is this idea that has been seized upon in the modern period to justify rebellion against nominally Muslim rulers. It has been argued, most famously by ʿAbd al-Salām Farāj in his treatise justifying armed revolt against the Egyptian government of Anwar Sadat, The Neglected Duty (al-Farīḍa al-Ghāʾiba), that imposing foreign, secular, non-Islamic laws on Muslims constitutes nothing less than apostasy from Islam, since God has proclaimed in the Qurʾān that “those who do not rule [judge] by what God has revealed, those are the unbelievers” (5:44). As unbelievers, such rulers may be killed as apostates or rebelled against as traitors. Thus the classical principle of obedience to any ruler who provides security and stability (reaffirmed, if awkwardly, by the clerics of al-Azhar during the anti-Mubarak uprising of January and February 2011) collapses into a tautology reminiscent of the early Khārijite doctrine: Muslims are commanded to obey their rulers; rulers are commanded to enforce the Sharīʿah; departure from the Sharīʿah negates the obligation to obey; those subject to power will judge what constitutes departure from the Sharīʿah. This is the precise logic of replacing the will and judgment of the ruler with one’s own understanding of God’s will, which horrified Sunnī scholars in the eighth century (as well as Thomas Hobbes in the seventeenth century).

While few Muslims embrace the utopianism and Sharīʿah-formalism of Farāj and his heirs in the radical Islamist movement, many no longer accept the near-absolute duty of obedience often asserted in the Sunnī tradition. The Green Movement in Iran and the events of the Arab Spring seem to have consigned( the “better thirty years of injustice than a day of fitna” doctrine to the proverbial dustbin of history. Events now have caught up with a century of thinking, some of it tentative or formulaic, about how to institutionalize traditional Islamic commitments to political justice, the rule of law, and the duty to consult within modern constitutional and democratic forms.

Social Justice

Another modern contribution to the Islamic tradition of thinking about justice is the discourse on “social justice.” In response to both the eruption of what is sometimes called “the social question” in Muslim societies (mass poverty or inequality combined with the emergence of mass politics) and the challenge of avowedly secular socialist or communist ideologies and movements, many twentieth-century Muslim thinkers rediscovered a commitment to “social justice” within Islamic ethics. Thinkers such as Sayyid Quṭb recast Islam as a religion not only of charity and care, but of social solidarity (takāful), or, as in the case of ʿAlī Sharīʿatī in Iran, a religion of revolutionary socialism.

One of the most common themes of modern Islamic political thought across the ideological spectrum is that Islam is superior to other religions like Christianity and other ideological rivals like socialism because it is the only doctrine or ideology that takes all of man’s innate needs equally seriously. A common Muslim reading of Christianity is that it is merely a religion of the spirit and thus either impossibly demanding (“love thy enemy”; “turn the other cheek”; “harder to get a rich man into heaven than a camel through the eye of a needle”) or unacceptably antinomian and libertine (since all that matters is faith and works are in vain). Similarly, a common reading of socialist ideologies is that they are merely materialist, only concerned with man’s body. Islam, so goes the refrain from Muḥammad ʿAbduh and Rashīd Riḍa through Sayyid Quṭb, al-Mawdūdī, and Ayatollah Khomeini to ʿAlī Sharīʿatī, is the “natural religion” (dīn al-fiṭra), which on this modern reading comes to mean the religion that responds to all of man’s psychological, emotional, material, and spiritual inclinations. Thus Muslims can have all of the care and solidarity of a socialist safety net while sacrificing neither their spiritual yearnings nor, crucially, their natural and understandable desire to be rewarded for their efforts and pass on their wealth to their children.

In Sayyid Quṭb’s case, the problem of social justice is given a politico-moral twist reminiscent of Rousseau. Made of both clay and God’s spirit (38:71–72), both good and evil, man naturally inclines toward the morality called for by God, according to Quṭb. However, in order to remain true to this morality, he needs not only personal commitment and a cultivated moral disposition, but the security that comes only from the faith that all of his fellows in society are equally so committed and from emancipation from domination by other humans—a political regime that not only enforces the letter of Islamic morality, but also exemplifies the principle of human subjugation only to God. In addition to domination or oppression, the innate inclination to morality can be undone by the fear, need, and servility that come from poverty. Whatever nobility the grateful, pious pauper may have in Quṭb’s eyes, the average man will be morally disfigured by the experience, unable to experience the security and dignity needed for the development of moral personality. Thus the need for an economic regime that not only enforces the letter of Islamic rules regarding charity, but also exemplifies the belief that all property belongs ultimately only to God. Social justice is therefore not only an obligation incumbent on Muslims, but the secret to the realism and feasibility of Islam’s utopian vision. The Muslim who experiences social justice will not only have no further grievances, but will experience no atavistic desires or motives contrary to the demands of religious morality.

Concept Of Justice

702 – 003

https://discerning-Islam.org

Last Updated: 12/2021

Copyright © 2017-2021 Institute for the Study of Islam (ISI) | Institute-for-the-study-of-Islam-org | Discerning Islam | Discerning-Islam.org | Commentaries on Islam | © 2020 Tips Of The Iceberg | © 1978 marketplace-values.org | Values In The Marketplace | are considered “Trade Marks and Trade Names” ®️ by the Colorado Secretary of State and the Oklahoma Secretary of State. All Rights Reserved.