The Levant: Yesterday & Today

The Ancient Levant

The Levant is a geographical term that refers to a large area in Southwest Asia, south of the Taurus Mountains, bounded by the Mediterranean Sea in the west, the Arabian Desert in the south, and Mesopotamia in the east. It stretches 400 miles north to south from the Taurus Mountains to the Sinai desert, and 70 to 100 miles east to west between the sea and the Arabian desert. In its narrowest sense, it is equivalent to the historical region of Syria. In its widest historical sense, the Levant included all of the eastern Mediterranean with its islands; that is, it included all of the countries along the Eastern Mediterranean shores, extending from Greece to Cyrenaica. The term is also sometimes used to refer to modern events or states in the region immediately bordering the eastern Mediterranean Sea: Cyprus, Israel, Palestine, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria.

The term entered English in the late 15th century from French. It derives from the Italian Levante, meaning “rising,” implying the rising of the sun in the east, and is broadly equivalent to the term Al-Mashriq meaning “the land where the sun rises.”

The term normally does not include Anatolia (although at times Cilicia may be included), the Caucasus Mountains, Mesopotamia or any part of the Arabian Peninsula proper. The Sinai Peninsula is sometimes included, though it is more considered an intermediate, peripheral or marginal area forming a land bridge between the Levant and northern Egypt.

In modern scholarship the chronology of the Bronze age Levant is divided into Early/Proto Syrian, corresponding to the Early Bronze; Old Syrian, corresponding to the Middle Bronze; and Middle Syrian, corresponding to the Late Bronze. The term Neo-Syria is used to designate the early Iron Age.

The old Syrian period was dominated by the Eblaite first kingdom, Nagar and the Mariote second kingdom. The Akkadian Empire conquered large areas of the Levant and were followed by the Amorite kingdoms, ca. 2000–1600 BC, which arose in Mari, Yamkhad and Qatna. Also following the Akkadians was the extension of Khirbet Kerak ware culture, showing affinities with the Caucasus, and possibly linked to the later appearance of the Hurrians.

Around the 17th and 16th centuries BC most of the older centers had been overrun. The Mitanni, for a time, menaced the Hittite kingdom, but were defeated by it around the middle of the 14th century BC. The Semitic Hyksos used the new technologies to occupy Egypt, but were expelled, leaving the empire of the New Kingdom to develop in their wake. From 1550 until 1100 BC, much of the Levant was conquered by Egypt, which in the latter half of this period contested Syria with the Hittite Empire.

At the end of the 13th century BC, all of these powers suddenly collapsed. Cities all around the eastern Mediterranean were sacked within a span of a few decades by assorted raiders. The Hittite empire was destroyed. Egypt repelled its attackers with only a major effort, and over the next century shrank to its territorial core, its central authority permanently weakened.

Stone Age

Anatomically modern Homo sapiens are demonstrated at the area of Mount Carmel, during the Middle Paleolithic dating from about c. 90,000 BC. This move out of Africa seems to have been unsuccessful and by c. 60,000 BC in Palestine/Israel/Syria, especially at Amud, classic Neanderthal groups seem to have profited from the worsening climate to have replaced Homo sapiens, who seem to have been confined once more to Africa.

A second move out of Africa is demonstrated by the Boker Tachtit Upper Paleolithic culture, from 52–50,000 BC, with humans at Ksar Akil XXV level being modern humans. This culture bears close resemblance to the Badoshan Aurignacian culture of Iran, and the later Sebilian I Egyptian culture of c. 50,000 BC. Stephen Oppenheimer, a British pediatrician, geneticist, and writer, suggests that this reflects a movement of modern human (possibly Caucasian) groups back into North Africa, at this time.

It would appear this sets the date by which Homo sapiens Upper Paleolithic cultures begin replacing Neanderthal Levalo-Mousterian, and by c. 40,000 BC Palestine was occupied by the Levanto-Aurignacian Ahmarian culture, lasting from 39–24,000 BC. This culture was quite successful spreading as the Antelian culture (late Aurignacian), as far as Southern Anatolia, with the Atlitan culture.

After the Late Glacial Maxima, a new Epipaleolithic culture appears in Southern Palestine. Extending from 18–10,500 BC, the Kebaran culture shows clear connections to the earlier Microlithic cultures using the bow and arrow, and using grinding stones to harvest wild grains, that developed from the c. 24,000–17,000 BC Halfan culture of Egypt, that came from the still earlier Aterian tradition of the Sahara. Some linguists see this as the earliest arrival of Nostratic languages in the Middle East. Kebaran culture was quite successful, and may have been ancestral to the later Natufian culture (10,500–8,500 BC), which extended throughout the whole of the Levantine region. These people pioneered the first sedentary settlements, and may have supported themselves from fishing, and from the harvest of wild grains plentiful in the region at that time.

Natufian culture also demonstrates the earliest domestication of the dog, and the assistance of this animal in hunting and guarding human settlements may have contributed to the successful spread of this culture. In the northern Syrian, eastern Anatolian region of the Levant, Natufian culture at Cayonu and Mureybet developed the first fully agricultural culture with the addition of wild grains, later being supplemented with domesticated sheep and goats, which were probably domesticated first by the Zarzian culture of Northern Iraq and Iran (which like the Natufian culture may have also developed from Kebaran).

By 8,500–7,500 BC, the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) culture developed out of the earlier local tradition of Natufian in Southern Palestine, dwelling in round houses, and building the first defensive site at Jericho (guarding a valuable fresh water spring). This was replaced in 7,500 BC by Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB), dwelling in square houses, coming from Northern Syria and the Euphrates bend.

During the period of 8,500–7,500 BC, another hunter-gatherer group, showing clear affinities with the cultures of Egypt (particularly the Outacha retouch technique for working stone) was in Sinai. This Harifian culture may have adopted the use of pottery from the Isnan culture and Helwan culture of Egypt (which lasted from 9,000 to 4,500 BC), and subsequently fused with elements from the PPNB culture during the climatic crisis of 6,000 BC to form what Juris Zarins calls the Syro-Arabian pastoral technocomplex, which saw the spread of the first Nomadic pastoralists in the Ancient Near East. These extended southwards along the Red Sea coast and penetrating the Arabian bifacial cultures, which became progressively more Neolithic and pastoral, and extending north and eastwards, to lay the foundations for the tent-dwelling Martu and Akkadian peoples of Mesopotamia.

In the Amuq valley of Syria, PPNB culture seems to have survived, influencing further cultural developments further south. Nomadic elements fused with PPNB to form the Minhata Culture and Yarmukian Culture which were to spread southwards, beginning the development of the classic mixed farming Mediterranean culture, and from 5,600 BC were associated with the Ghassulian culture of the region, the first chalcolithic culture of the Levant. This period also witnessed the development of megalithic structures, which continued into the Bronze Age.

Iron Age

The destruction at the end of the Bronze Age left a number of tiny kingdoms and City-states behind. A few Hittite centers remained in northern Syria, along with some Phoenician ports in Canaan that escaped destruction and developed into great commercial powers. The Israelites emerged as a rural culture (possibly from the displaced Canaanite refugees escaping the Bronze Age Collapse to Judea and Samaria alongside groups like the Shasu and the Habiru) mainly in the Canaanite hill-country and the Eastern Galilee, quickly spreading through the land and forming an alliance in the struggle for the land against the Philistines to the West, Moab and Ammon to the East and Edom to the South. In the 12th century BC, most of the interior, as well as Babylonia, was overrun by Arameans, while the shoreline around today’s Gaza Strip was settled by Philistines.

In this period a number of technological innovations spread, most notably iron working and the Phoenician alphabet, developed by the Phoenicians or the Canaanites around the 16th century BC.

During the 9th century BC, the Assyrians began to reassert themselves against the incursions of the Aramaeans, and over the next few centuries developed into a powerful and well-organized empire. Their armies were among the first to employ cavalry, which took the place of chariots, and had a reputation fo “””.r kboth prowess and brutality. At their height, the Assyrians dominated all of the Levant, Egypt, and Babylonia. However, the empire began to collapse toward the end of the 7th century BC, and was obliterated by an alliance between a resurgent New Kingdom of Babylonia and the Iranian Medes.

During the 9th century BC, the Assyrians began to reassert themselves against the incursions of the Aramaeans, and over the next few centuries developed into a powerful and well-organized empire. Their armies were among the first to employ cavalry, which took the place of chariots, and had a reputation fo “””.r kboth prowess and brutality. At their height, the Assyrians dominated all of the Levant, Egypt, and Babylonia. However, the empire began to collapse toward the end of the 7th century BC, and was obliterated by an alliance between a resurgent New Kingdom of Babylonia and the Iranian Medes.

The subsequent balance of power was short-lived, though. In the 550s BC the Persians revolted against the Medes and gained control of their empire, and over the next few decades annexed to it the realms of Lydia in Anatolia, Damascus, Babylonia, and Egypt, as well as consolidating their control over the Iranian plateau nearly as far as India. This vast kingdom was divided up into various satrapies and governed roughly according to the Assyrian model, but with a far lighter hand. Around this time Zoroastrianism became the predominant religion in Persia.

Classical Age

Persia controlled the Levant but by the 4th century BC, Persia had fallen into decline. The campaigns of Xenophon illustrated how very vulnerable Persia had become to attack by an army organized along Greek lines, and under Alexander the Great the Levant was conquered.

Alexander did not live long enough to consolidate his realm, the greater share of the east went to the descendants of Seleucus I Nicator. This period saw great innovations in mathematics, science, architecture, and the like, and Greeks founded cities throughout the east, some of which grew to be the world’s first major metropolises. Their culture did not, however, reach very far into the countryside.

The Seleucids adopted a pro-western stance that alienated both the powerful eastern satraps and the Greeks who had migrated to the east. During the 2nd century BC, Greek culture lost ground there, and the empire began to break apart. The Seleucid kingdom continued to decline and its remaining provinces were annexed by the Roman Republic in 64 BC as Iudaea Province.

Persian dynasty, the Sassanids, entered in conflicts with Rome, and later with the Byzantine Empire. In 391, the Byzantine era began with the permanent division of the Roman Empire into East and Western halves. Byzantine control over the sites of Israel and Judah and other parts of the Levant lasted until 636, when it was conquered by Arabs and became a part of the Caliphate.

The Byzantines reached their lowest point under Phocas, with the Sassanids occupying the whole of the eastern Mediterranean. In 610, though, Heraclius took the throne of Constantinople and began a successful counter-attack, expelling the Persians and invading Media and Assyria. Unable to stop his advance, Khosrau II was assassinated and the Sassanid empire fell into anarchy. Weakened by their quarrels, neither empire was prepared to deal with the onslaught of the Arabs, newly unified under the banners of Islam and anxious to expand their faith. By 650, Arab forces had conquered all of Persia, Syria, and Egypt.

Levant

In the 13th and 14th centuries, the term levante was used for Italian maritime commerce in the Eastern Mediterranean, including Greece, Anatolia, Syria-Palestine, and Egypt, that is, the lands east of Venice. Eventually the term was restricted to the Muslim countries of Syria-Palestine and Egypt. In 1581, England set up the Levant Company to monopolize commerce with the Ottoman Empire. The name Levant States was used to refer to the French mandate over Syria and Lebanon after World War I. This is probably the reason why the term Levant has come to be used more specifically to refer to modern Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Israel, Jordan, and Cyprus. Some scholars misunderstood the term thinking that it derives from the name of Lebanon. Today the term is often used in conjunction with prehistoric or ancient historical references. It has the same meaning as “Syria-‘Palestine” or Ash-Shaam, the area that is bounded by the Taurus Mountains of Turkey in the North, the Mediterranean Sea in the west, and the north Arabian Desert and Mesopotamia in the east. It does not include Anatolia (also called Asia Minor), the Caucasus Mountains, or any part of the Arabian Peninsula proper. Cilicia (in Asia Minor) and the Sinai Peninsula (Asian Egypt) are sometimes included.

The term Levant was widely used to describe the region from the 18th to the mid-19th centuries, and has had steady but lower usage since the late 19th century; several dictionaries consider it to be archaic today. Both the noun Levant and the adjective Levantine are now commonly used to describe the ancient and modern culture area formerly called Syro-Palestinian or biblical: archaeologists now speak of the Levant and of Levantine archaeology; food scholars speak of Levantine cuisine; and the Latin Christians of the Levant continue to be called Levantine Christians.

The Levant has been described as the “crossroads of western Asia, the eastern Mediterranean, and northeast Africa,” and the “northwest of the Arabian plate.” The populations of the Levant share not only the geographic position, but cuisine, some customs, and a very long history. They are often referred to as Levantines.

Etymology

The term Levant, which appeared in English in 1497, originally meant the East in general or “Mediterranean lands east of Italy.” It is borrowed from the French levant “rising,” referring to the rising of the sun in the east, or the point where the sun rises. The phrase is ultimately from the Latin word levare, meaning ‘lift, raise.’ Similar etymologies are found in Greek Ἀνατολή (Anatolē, cf. Anatolia), in Germanic e (literally, “morning land”), in Italian (as in “Riviera di Levante,” the portion of the Liguria coast east of Genoa), in Hungarian Kelet, in Spanish and Catalan Levante and Llevant, (“the place of rising”), and in Hebrew (Hebrew: mizrāḥ). Most notably, “Orient” and its Latin source oriens meaning “east,” is literally “rising,” deriving from Latin orior “rise.”

The notion of the Levant has undergone a dynamic process of historical evolution in usage, meaning, and understanding. While the term “Levantine” originally referred to the European residents of the eastern Mediterranean region, it later came to refer to regional “native” and “minority” groups.

The term became current in English in the 16th century, along with the first English merchant adventurers in the region; English ships appeared in the Mediterranean in the 1570s, and the English merchant company signed its agreement (“capitulations”) with the Ottoman Sultan in 1579. The English Levant Company was founded in 1581 to trade with the Ottoman Empire, and in 1670 the French Compagnie du Levant was founded for the same purpose. At this time, the Far East was known as the “Upper Levant.”

In early 19th-century travel writing, the term sometimes incorporated certain Mediterranean provinces of the Ottoman empire, as well as independent Greece (and especially the Greek islands). In 19th-century archaeology, it referred to overlapping cultures in this region during and after presentations times, intending to reference the place instead of any one culture. The French mandate of Syria and Lebanon (1920–1946) was called the Levant states.

Geography And Modern-Day Use Of The Term

Today, “Levant” is the term typically used by archaeologists and historians with reference to the history of the region. Scholars have adopted the term Levant to identify the region due to it being a “wider, yet relevant, cultural corpus” that does not have the “political overtones” of Syria-Palestine. The term is also used for modern events, peoples, states or parts of states in the same region, namely Cyprus, Egypt, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Syria, and Turkey are sometimes considered Levant countries (compare with Near East, Middle East, Eastern Mediterranean and Western Asia). Several researchers include the island of Cyprus in Levantine studies, including the Council for British Research in the Levant, the UCLA Near Eastern Languages and Cultures department, Journal of Levantine Studies and the UCL Institute of Archaeology, the last of which has dated the connection between Cyprus and mainland Levant to the early Iron Age. Archaeologists seeking a neutral orientation that is neither biblical nor national have used terms such as Levantine archaeology and archaeology of the Southern Levant.

While the usage of the term “Levant” in academia has been restricted to the fields of archeology and literature, there is a recent attempt to reclaim the notion of the Levant as a category of analysis in political and social sciences. Two academic journals were recently launched: Journal of Levantine Studies, published by the Van Leer Jerusalem Institute and The Levantine Review, published by Boston College.

The word Levant has been used in some translations of the term ash-Shām as used by the terror organization known as ISIL, ISIS, and IS, though there is disagreement as to whether this translation is accurate.

History

Politics And Religion

The largest religious group in the Levant are the Muslims and the largest cultural-linguistic group are Arabs, due to the Muslim conquest of the Levant in the 7th century and subsequent Arabization of the region. Other large ethnic groups in the Levant include Jews, Kurds, Turkmens, Assyrians and Armenians.

The majority of Muslim Levantines are Sunni, Alawi, or Shi’a Muslim. There are also Jews, Christians, Yazidi Kurds, Druze, and other smaller sects.

Until the establishment of the modern State of Israel in 1948, Jews lived throughout the Levant alongside Muslims and Christians; since then, almost all have been expelled from their homes and sought refuge in Israel.

There are many Levantine Christian groups such as Greek, Oriental Orthodox (mainly Syriac Orthodox, Coptic, Georgian, and Maronite), Roman Catholic, Nestorian, and Protestant. Armenians mostly belong to the Armenian Apostolic Church. There are Levantines or Franco-Levantines who are mostly Roman Catholic. There are also Circassians, Turks, Samaritans, and Nawars. There are Assyrian peoples belonging to the Assyrian Church of the East (autonomous) and the Chaldean Catholic Church (Catholic).

In addition, this region has a number of sites that are of religious significance, such as Al-Aqsa Mosque, the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, and the Western Wall in Jerusalem.

Language

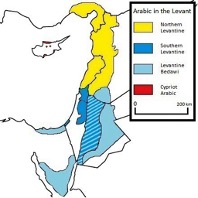

Map representing the distribution of the Arabic dialects in the area of the Levant.

Most populations in the Levant speak Levantine Arabic (Šāmī), usually classified as the varieties North Levantine Arabic in Lebanon, Syria, and parts of Turkey, and South Levantine Arabic in Palestine and Jordan. Each of these encompasses a spectrum of regional or urban/rural variations. In addition to the varieties normally grouped together as “Levantine,” a number of other varieties and dialects of Arabic are spoken in the Levant area, such as Levantine Bedawi Arabic and Mesopotamian Arabic.

Among the languages of Israel, the official language is Hebrew; Arabic was until July 19, 2018, also an official language. The Arab minority, in 2018, about 21 percent of the population of Israel, speaks a dialect of Levantine Arabic essentially indistinguishable from the forms spoken in the Palestinian territories.?’

Of the languages of Cyprus, the majority language is Greek, followed by Turkish (in the north). Two minority languages are recognized: Armenian, and Cypriot Maronite Arabic, a hybrid of mostly medieval Arabic vernaculars with strong influence from contact with Greek, spoken by approximately 1000 people.

Some communities and populations speak Aramaic, Greek, Armenian, Circassian, French, or English.

:August Jochmus’s The Syrian War and the Decline of the Ottoman Empire, 1840-1848: In Reports, Documents, and Correspondences, Etc, Volume 1, published in 1883, stated that Italian was previously the most common western European language in the Levant, but that it was being replaced by French.

:August Jochmus’s The Syrian War and the Decline of the Ottoman Empire, 1840-1848: In Reports, Documents, and Correspondences, Etc, Volume 1, published in 1883, stated that Italian was previously the most common western European language in the Levant, but that it was being replaced by French.

THE LEVANT: Yesterday & Today

501 – 001

https://discerning-Islam.org

Last Update: 04/2021