Islamic Schools And Branches: Part II

Schools Of Islamic theology

Set Of Beliefs Associated With The Islamic Faith

Schools of Islamic theology are various Islamic schools and branches in different schools of thought regarding aqidah (creed). According to Muhammad Abu Zahra: Qadariyah, Jahmis, Murji’ah, Muʿtazila, Batiniyya, Ash’ari, Maturidi, Athari are the ancient schools of aqidah.

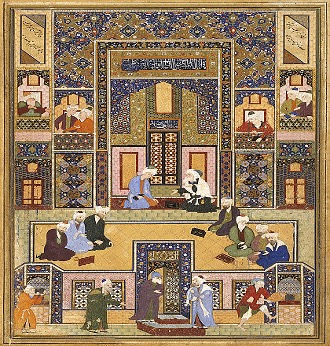

“The Meeting of the Theologians” by Abd Allah Musawwir, mid-16th century

The main split between Sunni and Shi’a Islam was initially more political than theological, but over time theological differences have developed. Still, differences in aqidah occur as divisions orthogonal to the main divisions in Islam along political or fiqh lines, such that a Muʿtazili might, for example, belong to Ja’fari, Zaidi or even Hanafi school of jurisprudence.

Divinity Schools In Islam

Aqidah is an Islamic term meaning “creed” or “belief.” Any religious belief system, or creed, can be considered an example of aqidah. However this term has taken a significant technical usage in Muslim history and theology, denoting those matters over which Muslims hold conviction. The term is usually translated as “theology.” Such traditions are divisions orthogonal to sectarian divisions of Islam, and a Mu’tazili may for example, belong to Jafari, Zaidi or even Hanafi school of jurisprudence. One of the earliest systematic theological school to develop, in the mid 8th-century, was Mu’tazila. It emphasized reason and rational thought, positing that the injunctions of Allah are accessible to rational thought and inquiry and that the Qur’an, albeit the word of Allah, was created rather than uncreated, which would develop into one of the most contentious questions in Islamic theology.

In the 10th century, the Ash’ari school developed as a response to Mu’tazila, leading to the latter’s decline. Ash’ari still taught the use of reason in understanding the Qur’an, but denied the possibility to deduce moral truths by reasoning . This was opposed by the school of Maturidi, which taught that certain moral truths may be found by the use of reason without the aid of revelation.

Another point of contention was the relative position of iman (“faith”) vs. taqwa (“piety”). Such schools of theology are summarized under Ilm al-Kalam, or “science of discourse,” as opposed to mystical schools who deny that any theological truth may be discovered by means of discourse or reason.

Sunni Schools Of Theology

Sunni Muslims are the largest denomination of Islam and are known as Ahl as-Sunnah wa’l-Jamā‘h or simply as Ahl as-Sunnah. The word Sunni comes from the word sunnah, which means the teachings and actions or examples of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. Therefore, the term “Sunni” refers to those who follow or maintain the sunnah of the prophet Muhammad.

The Sunnis believe that Muhammad did not appoint a successor to lead the Muslim ummah (community) before his death, and after an initial period of confusion, a group of his most prominent companions gathered and elected Abu Bakr Siddique, Muhammad’s close friend and a father-in-law, as the first caliph of Islam. Sunni Muslims regard the first four caliphs (Abu Bakr, `Umar ibn al-Khattāb, Uthman Ibn Affan and Ali ibn Abu Talib) as “al-Khulafā’ur-Rāshidūn” or “The Rightly Guided Caliphs.” After the Rashidun, the position turned into a hereditary right and the caliph’s role was limited to being a political symbol of Muslim strength and unity.

Athari

Atharism is a movement of Islamic scholars who reject rationalistic Islamic theology (kalam) in favor of strict textualism in interpreting the Qur’an. The name is derived from the Arabic word athar, literally meaning “remnant” and also referring to a “narrative.” Their disciples are called the Athariyya, or Atharis.

For followers of the Athari movement, the “clear” meaning of the Qur’an, and especially the prophetic traditions, has sole authority in matters of belief, and to engage in rational disputation (kalam), even if one arrives at the truth, is absolutely forbidden. Atharis engage in an amodal reading of the Qur’an, as opposed to one engaged in Ta’wil (metaphorical interpretation). They do not attempt to conceptualize the meanings of the Qur’an rationally, and believe that the “real” meaning should be consigned to Allah alone (tafwid). In essence, the meaning has been accepted without asking “how” or “Bi-la kaifa.”

On the other hand, the famous Hanbali scholar Ibn al-Jawzi states, in Kitab Akhbar as-Sifat, that Ahmad ibn Hanbal would have been opposed to anthropomorphic interpretations of Qur’anic texts such as those of al-Qadi Abu Ya’la, Ibn Hamid and Ibn az-Zaghuni. Based on Abu’l-Faraj ibn al-Jawzi’s criticism of Athari-Hanbalis, Muhammad Abu Zahra, a Professor of Islamic law at Cairo University deduced that Salafi aqidah is located somewhere between ta’tili and anthropopathy (Absolute Ẓāhirīsm in understanding the tashbih in Qur’an) in Islam. Absolute Ẓāhirīsm and total rejection of ta’wil are amongst the fundamental characteristics of this “new” Islamic school of theology.

Ilm al-Kalām

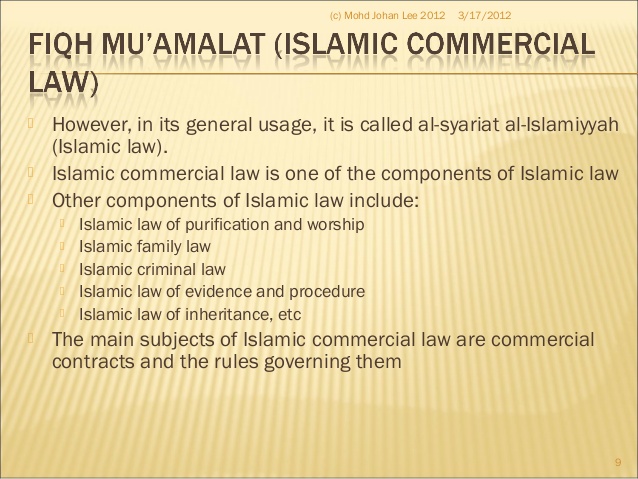

ʿIlm al-Kalām, usually foreshortened to kalam and sometimes called “Islamic scholastic theology,” is a rational undertaking born out of the need to establish and defend the tenets of Islamic faith against doubters and detractors. ‘Ilm al-Kalam incorporates Aristotelian reasoning and logic into Islamic theology. A scholar of kalam is referred to as a mutakallim (plural mutakallimūn) as distinguished from philosophers, jurists, and scientists. There are many possible interpretations as to why this discipline was originally called “kalam”; one is that the widest controversy in this discipline has been about whether the Word of Allah, as revealed in the Qur’an, can be considered part of Allah’s essence and therefore not created, or whether it was made into words in the normal sense of speech, and is therefore created.

Ash’ariyyah

The Mu’tazila were challenged by Abu al-Hasan Al-Ash’ari, who famously defected from the Mu’tazila and formed the rival Ash’ari school of theology. The Ash’ari school took the opposite position of the Mu’tazila and insisted that truth cannot be known through reason alone. The Ash’ari school further claimed that truth can only be known through revelation. The Ash’ari claim that without revelation, the unaided human mind would not be able to know if something is good or evil.

Today, the Ash’ari school is considered one of the Orthodox schools of theology. The Ash’ari school is the basis of the Shafi’i school of jurisprudence, which has supplied it with most of its most famous disciples. The most famous of these are Abul-Hassan Al-Bahili, Abu Bakr Al-Baqillani, al-Juwayni, Al-Razi and Al-Ghazali. Thus Al-Ash`ari’s school became, together with the Maturidi, the main schools reflecting the beliefs of the Sunnah.

Mâtûrîd’iyyah

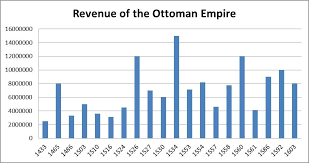

The Maturidi school was founded by Abu Mansur Al Maturidi, and is the most popular theological school amongst Muslims, especially in the areas formerly controlled by the Ottomans and the Mughals. Today, the Maturidi school is the position favored by the ahl al-ra’y (people of reason), which includes the Hanafi and Maliki schools of fiqh who make up the majority of Muslims.

The Maturidi school takes the middle position between the Ash’ari and Mu’tazili schools on the questions of knowing truth and free will. The Maturidis say that the unaided human mind is able to find out that some of the more major sins such as alcohol or murder are evil without the help of revelation, but still maintain that revelation is the ultimate source of knowledge. Additionally, the Maturidi believe that Allah created and can control all of His creation, but that he allows humans to make individual decisions and choices for themselves.

Jahmis were the followers of the Islamic theologian Jahm bin Safwan who associate himself with Al-Harith ibn Surayj. He was an exponent of extreme determinism according to which a man acts only metaphorically in the same way in which the sun acts or does something when it sets. This is the position adopted by the Ash’ari school, which holds that Allah’s omnipotence is absolute and perfect over all creation.

Qadariyyah

Qadariyyah is an originally derogatory term designating early Islamic theologians who asserted human beings are ontologically free and have a perfect free will, whose exercise justifies divine punishment and absolving Allah of responsibility for evil in the world. Their doctrines were adopted by the Mu’tazilis and rejected by the Ash’aris. The tension between free will and Allah’s omnipotence was later reconciled by the Maturidi school of theology, which asserted that Allah grants human beings their agency, but can remove or otherwise alter it at any time.

Muʿtazila

The first group to pursue this undertaking were the Mu’tazila, who asserted that all truth could be known through reason alone. Mu’tazili theology originated in the 8th century in Basra when Wasil Ibn ‘Ata’ stormed out of a lesson of Hasan al-Basri following a theological dispute.

The Mu’tazila asserted that everything in revelation could be found through rational means alone. The Mu’tazila were heavily influenced by the Greek philosophy they encountered and began to adopt the ideas of Plotinus, whose Neoplatonic theology caused an enormous backlash against them. The political backlash the Mu’tazila faced, as well as the challenged brought forth by new schools of theology caused this group to atrophy and decline into irrelevancy. They are no longer considered an Orthodox school of theology by Sunni Muslims.

Bishriyya

Bishriyya followed the teachings of Bishr ibn al-Mu’tamir which were distinct from Wasil ibn Ata.

Bâ’ Hashim’iyyah

Bâh’ Sham’iyyah was a school of Mu’tazili thought, rivaling the school of Qadi Abd al-Jabbar, based primarily on the earlier teaching of Abu Hashim al-Jubba’i, the son of Abu ‘Ali Muhammad al-Jubba’i.

Muhakkima

The groups that were seceded from Ali’s army in the end of the Arbitration Incident constituted the branch of Muhakkima. They mainly divided into two major sects called as Kharijites and Ibadis.

Khawarij

The Kharijites considered the caliphate of Abu Bakr and Umar to be rightly guided but believed that Uthman ibn Affan had deviated from the path of justice and truth in the last days of his caliphate, and hence was liable to be killed or displaced. They also believed that Ali ibn Abi Talib committed a grave sin when he agreed on the arbitration with Muʿāwiyah. In the Battle of Siffin, Ali acceded to Muawiyah’s suggestion to stop the fighting and resort to negotiation. A large portion of Ali’s troops (who later became the first Kharijites) refused to concede to that agreement, and they considered that Ali had breached a Qur’anic verse which states that, “The decision is only for Allah” (Qur’an 6:57), which the Kharijites interpreted to mean that the outcome of a conflict can only be decided in battle (by Allah) and not in negotiations (by human beings).

The Kharijites thus deemed the arbitrators and Amr Ibn Al-As), the leaders who appointed these arbitrators (Ali and Muʿāwiyah) and all those who agreed on the arbitration (all companions of Ali and Muʿāwiyah) as Kuffār (disbelievers), having breached the rules of the Qur’an. They believed that all participants in the Battle of Jamal, including Talha, Zubair (both being companions of Muhammad) and Aisha had committed a Kabira (major sin in Islam).

Kharijites reject the doctrine of infallibility for the leader of the Muslim community, in contrast to Shi’a but in agreement with Sunnis. Modern-day Islamic scholar Abul Ala Maududi wrote an analysis of Kharijite beliefs, marking a number of differences between Kharijism and Sunni Islam. The Kharijites believed that the act of sinning is analogous to Kufr (disbelief) and that every grave sinner was regarded as a Kāfir (disbeliever) unless he repents. With this argument, they denounced all the above-mentioned Ṣaḥābah and even cursed and used abusive language against them. Ordinary Muslims were also declared disbelievers because first, they were not free of sin; secondly they regarded the above-mentioned Ṣaḥābah as believers and considered them as religious leaders, even inferring Islamic jurisprudence from the Hadeeth narrated by them. They also believed that it is not a must for the caliph to be from the Quraysh. Any pious Muslim nominated by other Muslims could be an eligible caliph. Additionally, Kharijites believed that obedience to the caliph is binding as long as he is managing the affairs with justice and consultation, but if he deviates, then it becomes obligatory to confront him, demote him and even kill him.

Ibadiyya

Ibadiyya has some common beliefs overlapping with Ashari, Mu’tazila, Sunni and some Shi’ites Murji’ah is an early Islamic school whose followers are known in English as “Murjites” or “Murji’ites.” The Murji’ah emerged as a theological school in response to the Kharijites on the early question about the relationship between sin and apostasy (rida). The Murji’ah believed that sin did not affect a person’s beliefs (iman) but rather their piety (taqwa). Therefore, they advocated the idea of “delayed judgement,” (irjaa). The Murji’ah maintain that anyone who proclaims the bare minimum of faith must be considered a Muslim, and sin alone cannot cause someone to become a disbeliever (kafir). The Murjite opinion would eventually dominate that of the Kharijites and become the mainstream opinion in Sunni Islam. The later schools of Sunni theology adopted their stance while form more developed theological schools and concepts.

Shi’a Schools Of Theology

Zaydi-Fivers

The Zaidi School of Divinity is close to the Mu’tazilite school. There are a few issues between both schools, most notably the Zaydi doctrine of the Imamate, which is rejected by the Mu’tazilites. Amongst the Shi’a, Zaydis are most similar to Sunnis since Zaydism shares similar doctrines and jurisprudential opinions with Sunni scholars.

Bāṭen’iyyah

The Bāṭen’iyyah ʿAqīdah, was originally introduced by Abu’l-Khāttāb Muhammad ibn Abu Zaynab al-Asadī, and later developed by Maymūn al-Qaddāh and his son ʿAbd Allāh ibn Maymūn for the esoteric interpretation of the Qur’an. The members of Batiniyyah may belong to either Ismailis or Twelvers.

Imami-Ismā’īlīs

The Ismā’īlī Imāmate differ from Twelvers because they had living imams or da’is for centuries. They followed Isma’il ibn Jafar, elder brother of Musa al-Kadhim, as the rightful Imam after his father Ja’far al-Sadiq. The Ismailis believe that whether Imam Ismail did or did not die before Imam Ja’far, he had passed on the mantle of the imāmate to his son Muḥammad ibn Ismā’īl al-Maktum as the next imam.

The followers of “Batiniyyah-Twelver” madh’hab consist of Alevis and Nusayris, who developed their own fiqh system and do not pursue the Ja’fari jurisprudence. Their combined population is close to 1 percent of World overall Muslim population.

Alevism

Alevis are sometimes categorized as part of Twelver Shi’a Islam, and sometimes as its own religious tradition, as it has markedly different philosophy, customs, and rituals. They have many Tasawwufī characteristics and express belief in the Qur’an and The Twelve Imams, but reject polygamy and accept religious traditions predating Islam, like Turkish shamanism. They are significant in East-Central Turkey. They are sometimes considered a Sufi sect, and have an untraditional form of religious leadership that is not scholarship oriented like other Sunni and Shi’a groups. Seven to eleven million Alevi people including the other denominations of Twelver Shi’ites live in Anatolia.

Alevi Islamic School Of Divinity

In Turkey, Shi’a Muslim people belong to the Ja’fari jurisprudence Madhhab, which tracks back to the sixth Shi’a Imam Ja’far al-Sadiq (also known as Imam Jafar-i Sadiq), are called as the Ja’faris, who belong to Twelver Shi’a. Although the Alevi Turks are being considered as a part of Twelver Shi’a Islam, their belief is different from the Ja’fari jurisprudence in conviction.

“The Alevi-Turks” has a unique and perplex conviction tracing back to Kaysanites Shi’a and Khurramites which are considered as Ghulat Shi’a. According to Turkish scholar Abdülbaki Gölpinarli, the Qizilbash (“Red-Heads”) of the 16th century – a religious and political movement in Azerbaijan that helped to establish the Safavid dynasty – were “spiritual descendants of the Khurramites.”

Among the members of the “Qizilbash-Tariqah” who are considered as a sub-sect of the Alevis, two figures firstly Abu Muslim Khorasani who assisted Abbasid Caliphate to beat Umayyad Caliphate, but later eliminated and murdered by Caliph Al-Mansur, and secondly Babak Khorramdin who incited a rebellion against the Abbasid Caliphate and consequently was killed by Caliph al-Mu’tasim are highly respected. This belief provides strong clues about their Kaysanites Shi’a and Khurramites origins. In addition, the “Safaviyya Tariqah” leader Ismail I is a highly regarded individual in the belief of “Alevi-Qizilbash-Tariqah” associating them with the Imamah (Shi’a Twelver doctrine) conviction of the “Twelver Shi’a Islam.”

Their aqidah (theological conviction) is based upon a syncretic fiqh system called as “Batiniyya-Sufism”which incorporates some Qarmatian sentiments, originally introduced by “Abu’l-Khāttāb Muhammad ibn Abu Zaynab al-Asadī,” and later developed by “Maymun al-Qāddāh” and his son “ʿAbd Allāh ibn Maymun,” and “Mu’tazila” with a strong belief in The Twelve Imams.

Not all of the members believe that the fasting in Ramadan is obligatory although some Alevi-Turks performs their fasting duties partially in Ramadan.

Some beliefs of Shamanism still are common amongst the Qizilbash Alevi-Turkish people in villages.

On the other hand, the members of Bektashi Order have a conviction of “Batiniyya Isma’ilism” and “Hurufism” with a strong belief in The Twelve Imams.

In conclusion, Qizilbash-Alevis are not a part of Ja’fari jurisprudence fiqh, even though they can be considered as members of different Tariqa of Shi’a Islam all looks like sub-classes of Twelver. Their conviction includes “Batiniyya-Hurufism” and “Sevener-Qarmatians-Ismailism” sentiments.

They all may be considered as special groups not following the Ja’fari jurisprudence, like Alawites who are in the class of Ghulat Twelver Shi’a Islam, but a special Batiniyya belief somewhat similar to Isma’ilism in their conviction.

In conclusion, Twelver branch of Shi’a Islam Muslim population of Turkey is composed of Mu’tazila aqidah of Ja’fari jurisprudence madhhab, Batiniyya-Sufism aqidah of Maymūn’al-Qāddāhī fiqh of the Alevīs, and Cillī aqidah of Maymūn ibn Abu’l-Qāsim Sulaiman ibn Ahmad ibn at-Tabarānī fiqh of the Alawites, who altogether constitutes nearly one third of the whole population of the country. (An estimate for the Turkish Alevi population varies between Seven and Eleven Million. Over 85 percent of the population, on the other hand, overwhelmingly constitute Maturidi aqidah of the Hanafi fiqh and Ash’ari aqidah of the Shafi’i fiqh of the Sunni followers).

ʿAqīdah Of Alevi-Islam Dīn Services

“What is Alevism, what is the understanding of Islam in Alevism? The answers to these questions, instead of the opposite of what’s known by many people is that the birthplace of Alevism was never in Anatolia. This is an example of great ignorance, that is, to tell that the Alevism was emerged in Anatolia. Searching the source of Alevism in Anatolia arises from unawareness. Because there was not even one single Muslim or Turk in Anatolia before a specific date. The roots of Alevism stem from Turkestan – Central Asia. Islam was brought to Anatolia by Turks in 10th and 11th centuries by a result of migration for a period of 100 – 150 years. Before this event took place, there were no Muslim and Turks in Anatolia. Anatolia was then entirely Christian. We Turks brought Islam to Anatolia from Turkestan. Professor İzzettin Doğan, The President of Alevi-Islam Religion Services. Some of the differences that mark Alevis from Shi’a Islam are the non-observance of the five daily prayers and prostrations (they only bow twice in the presence of their spiritual leader), Ramadan, and the Hajj (they consider the pilgrimage to Mecca an external pretense, the real pilgrimage being internal in one’s heart); and non-attendance of mosques.

Some of their members (or sub-groups) claim that Allah takes abode in the bodies of the human-beings (ḥulūl), believe in metempsychosis (tanāsukh), and consider Islamic law to be not obligatory (ibāḥa), similar to antinomianism.

Some of the Alevis criticizes the course of Islam as it is being practiced overwhelmingly by more than 99 percent of Sunni and Shi’a population.

They believe that major additions had been implemented during the time of Ummayads, and easily refuse some basic principles on the grounds that they believe it contradicts with the holy book of Islam, namely the Qur’an.

Regular daily salat and fasting in the holy month of Ramadan are officially not accepted by some members of Alevism.

Some of their sub-groups like Ishikists and Bektashis, who portrayed themselves as Alevis, neither comprehend the essence of the regular daily salat (prayers) and fasting in the holy month of Ramadan that is frequently accentuated at many times in Qur’an, nor admits that these principles constitute the ineluctable foundations of the Dīn of Islam as they had been laid down by Allah and they had been practiced in an uninterruptible manner during the period of Prophet Muhammad

Furthermore, during the period of Ottoman Empire, Alevis were forbidden to proselytize, and Alevism regenerated itself internally by paternal descent. To prevent penetration by hostile outsiders, the Alevis insisted on strict endogamy which eventually made them into a quasi-ethnic group. Alevi taboos limited interaction with the dominant Sunni political-religious centrex. Excommunication was the ultimate punishment threatening those who married outsiders, cooperated with outsiders economically, or ate with outsiders. It was also forbidden to use the state (Sunni) courts.

Baktāshism (Bektaşilik)

The founder of the Bektashiyyah sufi order Hacı Bektaş-ı Veli (Ḥājjī Baktāsh Walī), a murid of Malāmatī-Qalāndārī Sheikh Qutb ad-Dīn Haydar, who introduced the Ahmad Yasavi’s doctrine of “Four Doors and Forty Standing” into his tariqah.

Baktāshi Islamic School Of Divinity

The Bektashiyyah is a Shi’a Sufi order founded in the 13th century by Haji Bektash Veli, a dervish who escaped Central Asia and found refuge with the Seljuks in Anatolia at the time of the Mongol invasions (1219–1223). This order gained a great following in rural areas and it later developed in two branches: the Çelebi clan, who claimed to be physical descendants of Haji Bektash Veli, were called “Bel evladları” (children of the loins), and became the hereditary spiritual leaders of the rural Alevis; and the Babağan, those faithful to the path “Yol evladları” (children of the way), who dominated the official Bektashi Sufi order with, the “Unity of Being” that was formulated by Ibn Arabi. This has often been labeled as pantheism, although it is a concept closer to panentheism. Bektashism is also heavily permeated with Saaz concepts, such as the marked veneration of Ali, The Twelve Imams, and the ritual commemoration of Ashurah marking the Battle of Karbala. The old Persian holiday of Nowruz is celebrated by Bektashis as Imam Ali’s birthday.

In keeping with the central belief of Wahdat-ul-Wujood the Bektashi see reality contained in Haqq-Muhammad-Ali, a single unified entity. Bektashi do not consider this a form of trinity. There are many other practices and ceremonies that share similarity with other faiths, such as a ritual meal (muhabbet) and yearly confession of sins to a baba (magfirat-i zunub). Bektashis base their practices and rituals on their non-orthodox and mystical interpretation and understanding of the Qur’an and the prophetic practice (Sunnah). They have no written doctrine specific to them, thus rules and rituals may differ depending on under whose influence one has been taught. Bektashis generally revere Sufi mystics outside of their own order, such as Ibn Arabi, Al-Ghazali and Jelalludin Rumi who are close in spirit to them.

The Baktāshi ʿaqīdah

Four Spiritual Stations in Bektashiyyah: Shari’a, tariqa, haqiqa, and the fourth station, marifa, which is considered “unseen”, is actually the center of the haqiqa region. Marifa is the essence of all four stations.

The Bektashi Order is a Sufi order and shares much in common with other Islamic mystical movements, such as the need for an experienced spiritual guide — called a baba in Bektashi parlance — as well as the doctrine of “the four gates that must be traversed”: the “Shari’a” (religious law), “Tariqah” (the spiritual path), “Haqiqah” (truth), and “Marifa” (true knowledge).

Bektashis hold that the Qur’an has two levels of meaning: an outer (Zāher) and an inner (bāṭen). They hold the latter to be superior and eternal and this is reflected in their understanding of both the universe and humanity, which is a view that can also be found in Ismailism and Batiniyya.

Bektashism is also initiatic and members must traverse various levels or ranks as they progress along the spiritual path to the Reality. First level members are called aşıks. They are those who, while not having taken initiation into the order, are nevertheless drawn to it. Following initiation (called nasip) one becomes a mühip.

After some time as a mühip, one can take further vows and become a dervish. The next level above dervish is that of baba. The baba (lit. father) is considered to be the head of a tekke and qualified to give spiritual guidance (irshad). Above the baba is the rank of halife-baba (or dede, grandfather). Traditionally there were twelve of these, the most senior being the dedebaba (great-grandfather). The dedebaba was considered to be the highest ranking authority in the Bektashi| Order. Traditionally the residence of the dedebaba was the Pir Evi (The Saint’s Home) which was located in the shrine of Hajji Bektash Wali in the central Anatolian town of Hacıbektaş (Solucakarahüyük).

Islamic Schools And Branches: Part II

301 – 001-b

Last Update: 03/2021