Shi’a Islam

Shi’a is a branch of Islam which holds that the Islamic prophet Muhammad designated Ali ibn Abi Talib as his successor and the Imam (leader) after him, most notably at the event of Ghadir Khumm but was prevented caliphate as a result of Saqifah (Saqifah is significant for being the site where, after the Islamic prophet Muhammad died, some of Muhammad’s companions gathered and pledged allegiance to Abu Bakr. No one from Muhammad’s family was present at the event, and Ali ibn Abi .Talib, who had been declared the successor to Muhammad at the event of Ghadir Khumm, was performing Muhammad’s funeral rites when the event occurred) incident. This view primarily contrasts with that of Sunni Islam, whose adherents believe that Muhammad did not appoint a successor and consider Abu Bakr who they claim was appointed Caliph through a Shura (community consensus in Saqifah, to be the first rightful Caliph after the Prophet).

Unlike the first three Rashidun caliphs, Ali was from the same clan as Muhammad, Banu Hashim.

Adherents of Shi’a Islam are called Shi’as of Ali, Shi’as or the Shi’a as a collective or Shi’i or Shi’ite individually. Shi’a Islam is the second largest branch of Islam: in 2009, Shi’a Muslims constituted 10 percent -20 percent of the world’s Muslim population. Twelver Shi’a (Ithnā’ashariyyah – is the largest branch of Shi’a Islam. The term Twelver refers to its adherents’ belief in twelve divinely ordained leaders, known as the Twelve Imams, and their belief that the last Imam, Muhammad al-Mahdi, lives in occultation and will reappear as the promised ), Islam’s savior. According to Shi’a tradition, the Mahdi’s tenure will coincide with the Second Coming of Jesus Christ (Isa), who is to assist the Mahdi against the Masih ad-Dajjal (literally, the “false Messiah” or Antichrist).). is the largest branch of Shi’a Islam, with 2012 estimates saying that 85 percent of Shi’as were Twelvers.

Ali ibn Abi Talib

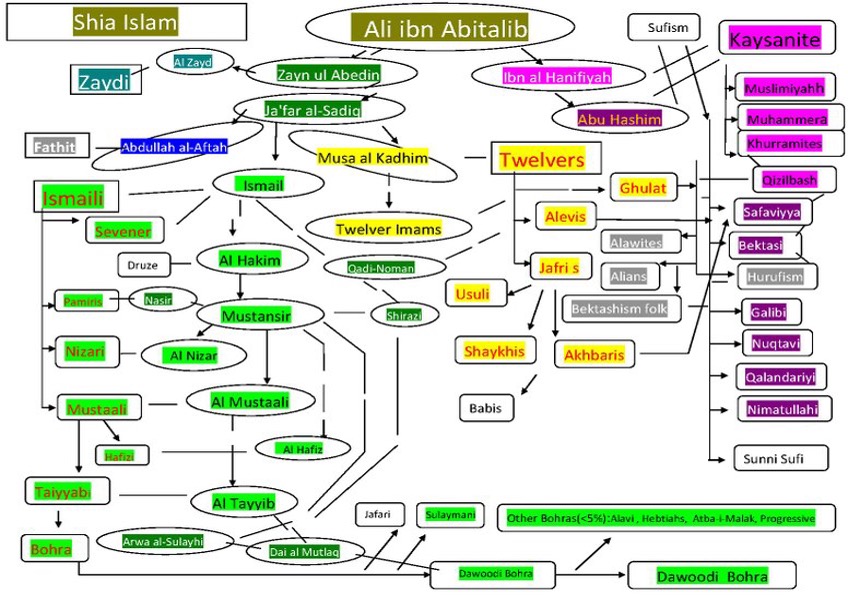

Shi’a Islam is based on the Qur’an and the message of Muhammad attested in hadith, and on hadith taught by their Imams. Shi’a consider Ali to have been divinely appointed as the successor to Muhammad, and as the first Imam. The Shi’a also extend this Imammah doctrine to Muhammad’s family, the Ahl al-Bayt (“the people/family of the House”), and some individuals among his descendants, known as Imams, who they believe possess special spiritual and political authority over the community, infallibility and other divinely ordained traits. Although there are many Shi’a subsects (minor Shi’a denominations), modern Shi’a Islam has been divided into three main groupings: Twelvers (already discussed), Ismailis (one of the Shi’a sects closest in terms of theology; Ismāʿīlī get their name from their acceptance of Imam Isma’il ibn Jafar as the appointed spiritual successor to Ja’far al-Sadiq, wherein they differ from the Twelvers who accept Musa al-Kadhim, younger brother of Isma’il, as the true Imām), Zaidis are named after Zayd ibn ʻAlī, the grandson of Husayn ibn ʻAlī and the son of their fourth Imam Ali ibn ‘Husain.) Followers of the Zaydi Islamic jurisprudence are called Zaydi and make up about 42 percent of Muslims in Yemen, with the vast majority of Shi’a Muslims in the country being Zaydi.

Ismāʿīlī get their name from their acceptance of Imam Isma’il ibn Jafar as the appointed spiritual successor to Ja’far al-Sadiq, wherein they differ from the Twelvers who accept Musa al-Kadhim, younger brother of Isma’il, as the true Imām) and Zaidis, with Twelver Shi’a being the largest and most influential group among Shi’a.

Etymology

The word Shi’a is the short form of the historic phrase shīʻatu ʻAlī meaning “followers of Ali,” “faction of Ali,” or “party of Ali.” Shi’a and Shi’ism are the forms used in English, while Shi’ite or Shi’ite, as well as Shi’a Ismailis (one of the Shia sects closest in terms of theology) refer to its adherents.

Terminology

The term for the first time was used at the time of Muhammad. At present, the word refers to the Muslims who believe that the leadership of the community after Muhammad belongs to Ali and his successors.

Beliefs

Shi’a Muslims believe that just as a prophet is appointed by Allah alone, only Allah has the prerogative to appoint the successor to his prophet. They believe Allah chose Ali to be Muhammad’s successor, infallible, the first caliph (khalifah, head of state) of Islam. The Shi’as believe that Muhammad designated Ali as his successor by Allah’s command (Eid Al Ghadir).

Ali was Muhammad’s first-cousin and closest living male relative as well as his son-in-law, having married Muhammad’s daughter Fatimah.

The Event Of Dhul Asheera

Muhammad invited people to Islam in secret for three years before he started inviting them publicly. In the fourth year of Islam, when Muhammad was commanded to invite his closer relatives to come to Islam he gathered the Banu Hashim clan in a ceremony. At the banquet, he was about to invite them to Islam when Abu Lahab interrupted him, after which everyone left the banquet. The Prophet ordered Ali to invite the 40 people again. The second time, Muhammad announced Islam to them and invited them to join. He said to them, “I offer thanks to Allah for His mercies. I praise Allah, and I seek His guidance. I believe in Him and I put my trust in Him. I bear witness that there is no god except Allah; He has no partners; and I am His messenger. Allah has commanded me to invite you to His religion by saying: And warn thy nearest kinsfolk. I, therefore, warn you, and call upon you to testify that there is no god but Allah, and that I am His messenger. O ye sons of Abdul Muttalib, no one ever came to you before with anything better than what I have brought to you. By accepting it, your welfare will be assured in this world and in the Hereafter. Who among you will support me in carrying out this momentous duty? Who will share the burden of this work with me? Who will respond to my call? Who will become my vicegerent, my deputy and my wazir?”

Ali was the only one to answer Muhammad’s call. Muhammad told him to sit down, saying, “Wait! Perhaps someone older than you might respond to my call.” Muhammad then asked the members of Banu Hashim a second time. Once again, Ali was the only one to respond, and again, Muhammad told him to wait. Muhammad then asked the members of Banu Hashim a third time. Ali was still the only volunteer. This time, Ali’s offer was accepted by Muhammad. Muhammad “drew [Ali] close, pressed him to his heart, and said to the assembly: ‘This is my wazir, my successor and my vicegerent. Listen to him and obey his commands.'” In another narration, when Muhammad accepted Ali’s eager offer, Muhammad “threw up his arms around the generous youth, and pressed him to his bosom” and said, “Behold my brother, my vizir, my vicegerent . . . Let all listen to his words, and obey him.”

The Event Of Ghadir Khumm

The event of Ghadir Khumm is an event that took place in March, 632. While returning from the Hajj pilgrimage, the Islamic prophet Muhammad gathered all the Muslims who were with him and gave< a long sermon. This sermon included Muhammad’s declaration that “to whomsoever I am Mawla, Ali is also their Mawla (a polysemous Arabic word, whose meaning varied in different periods and contexts. In the Qur’an and hadith it is used in two senses: Lord; and guardian, trustee, helper. In the pre-Islamic era the term originally applied to any form of tribal association. During the early Islamic era, this institution was adapted to incorporate new converts to Islam into the Arab-Muslim society and the word mawali gained currency as an appellation for non-Arab Muslims.).” After the sermon, Muhammad instructed everyone to pledge allegiance to Ali. Shi’a Muslims believe this event to be the official appointment of Ali as Muhammad’s successor.

A portion of the sermon Muhammad delivered, known as “The Farewell Sermon,” is as follows:

Oh people! Reflect on the Qur’an and comprehend its verses. Look into its clear verses and do not follow its ambiguous parts, for by Allah, none shall be able to explain to you its warnings and its mysteries, nor shall anyone clarify its interpretation, other than the one that I have grasped his hand, brought up beside myself, [and lifted his arm,] the one about whom I inform you that whomever I am his master (Mawla[a]), then Ali is his master (Mawla); and he is Ali Ibn Abi Talib, my brother, the executor of my will (Wasiyyi), whose appointment as your guardian and leader has been sent down to me from Allah, the mighty and the majestic.

— Muhammad, from The Farewell Sermon

The word mawla has many meanings in Arabic; however, Shi’as argue that the context of the sermon makes the meaning of “mawla” as “leader” in this context clear. Further, “mawla” was not the only word that Muhammad used in this sermon to describe Ali; he also used the words “wali,” “Imam,” and “khalifa.”. All of this together cements the leadership of Ali as described in the sermon delivered by Muhammad. Further, according to Shi’as, the combination of these words proves that Ali’s leadership, as described by Muhammad in this sermon, is both a religious leadership as well as a political leadership, as the meanings of these words indicate.

After the conclusion of Muhammad’s sermon, the Muslims were commanded to pledge their allegiance to Ali. Umar was reportedly the first to give the oath of allegiance to Ali.

Shi’a Muslims believe this to be Muhammad’s appointment of Ali as his successor.

Ali’s Caliphate

When Muhammad died in 632 AD, Ali and Muhammad’s closest relatives made the funeral arrangements. While they were preparing his body, Abu Bakr, Umar, and Abu Ubaidah ibn al Jarrah met with the leaders of Medina and elected Abu Bakr as caliph. Ali did not accept the caliphate of Abu Bakr and refused to pledge allegiance to him. This is indicated in both Sunni and Shi’a sahih and authentic Hadith.

Ibn Qutaybah, a 9th century Sunni Islamic scholar narrates of Ali: (scroll to the left).

I am the servant of Allah and the brother of the Messenger of Allah. I am thus more worthy of this office than you. I shall not give allegiance to you [Abu Bakr & Umar] when it is more proper for you to give bay’ah to me. You have seized this office from the Ansar using your tribal relationship to the Prophet as an argument against them. Would you then seize this office from us, the ahl al-bayt by force? Did you not claim before the Ansar that you were more worthy than they of the caliphate because Muhammad came from among you (but Muhammad was never from Abu Bakr family) – and thus they gave you leadership and surrendered command? I now contend against you with the same argument. It is we who are more worthy of the Messenger of Allah, living or dead. Give us ourdue right if you truly have faith in Allah, or else bear the charge of willfully doing wrong. Umar, I will not yield to your commands: I shall not pledge loyalty to him.' Ultimately, Abu Bakr said, "O 'Ali! If you do not desire to give your bay'ah, I am not going to force you for the same.’”

Ali’s wife, and daughter of Muhammad, Fatimah, refused to pledge allegiance to Abu Bakr and remained angry with him until she died due to the issues of Fadak (Fadak was a garden oasis in Khaybar, a tract of land in northern Arabia; it is now part of Saudi Arabia. Situated approximately 87mi/140 km from Medina, Fadak was known for its water wells, dates, and handicrafts; the oasis of Fadak was part of the bounty given to the Islamic prophet Muhammad, who gifted it to his daughter, Fatimah. The Sunni view is that it was not given to anyone, but preserved for the maintenance of Banu Hashim. Fadak became the object of dispute between Fatimah and the caliph Abu Bakr after Muhammad died.) and her inheritance from her father and the situation of Umar at Fatimah’s house. This is stated in sahih Sunni Hadith, Sahih Bukhari and Sahih Muslim. Fatimah did not at all pledge allegiance or acknowledge or accept the caliphate of Abu Bakr. Almost all of Banu Hashim, Muhammad’s clan and many of the sahaba, had supported Ali’s cause after the demise of the prophet while others supported Abu Bakr.

It was not until the murder of the third caliph, Uthman, in 657 AD that the Muslims in Medina in desperation invited Ali to become the fourth caliph as the last source, and he established his capital in Kufah in present-day Iraq.

Ali’s rule over the early Muslim community was often contested, and wars were waged against him. As a result, he had to struggle to maintain his power against the groups who betrayed him after giving allegiance to his succession, or those who wished to take his position. This dispute eventually led to the First Fitna (a civil war within the Rashidun Caliphate which resulted in the overthrowing of the Rashidun caliphs and the establishment of the Umayyad dynasty) which was the first major civil war within the Islamic Caliphate. The Fitna began as a series of revolts fought against Ali ibn Abi Talib, caused by the assassination of his political predecessor, Uthman ibn Affan. While the rebels who accused Uthman of prejudice affirmed Ali’s khilafa (caliph-hood), they later turned against him and fought him. Ali ruled from 656 AD to 661 AD, when he was assassinated while prostrating in prayer (sujud). Ali’s main rival, Muawiyah, then claimed the caliphate.

Hasan Ibn Ali

Upon the death of Ali, his elder son Hasan became leader of the Muslims of Kufa, and after a series of skirmishes between the Kufa Muslims and the army of Muawiyah, Hasan agreed to cede the caliphate to Muawiyah and maintain peace among Muslims upon certain conditions:

- The enforced public cursing of Ali, e.g. during prayers, should be abandoned;

- Muawiyah should not use tax money for his own private needs;

- There should be peace, and followers of Hasan should be given security and their rights;

- Muawiyah will never adopt the title of Amir al-Mu’minin;

- Muawiyah will not nominate any successor.

Hasan then retired to Medina, where in 670 AD he was poisoned by his wife Ja’da bint al-Ash’ath ibn Qays, after being secretly contacted by Muawiyah who wished to pass the caliphate to his own son Yazid and saw Hasan as an obstacle.

Husayn

Husayn, Ali’s younger son and brother to Hasan, initially resisted calls to lead the Muslims against Muawiyah and reclaim the caliphate. In 680 AD, Muawiyah died and passed the caliphate to his son Yazid, and breaking the treaty with Hasan ibn Ali. Yazid asked Husayn to swear allegiance (bay’ah) to him. Ali’s faction, having expected the caliphate to return to Ali’s line upon Muawiyah’s death, saw this as a betrayal of the peace treaty and so Husayn rejected this request for allegiance. There was a groundswell of support in Kufa for Husayn to return there and take his position as caliph and imam, so Husayn collected his family and followers in Medina and set off for Kufa. En route to Kufa, he was blocked by an army of Yazid’s men (which included people from Kufa) near Karbala (modern Iraq), and Husayn and approximately 72 of his family and followers were killed in the Battle of Karbala.

The Shi’as regard Husayn as a martyr (shahid), and count him as an Imam from the Ahl al-Bayt. They view Husayn as the defender of Islam from annihilation at the hands of Yazid I. Husayn is the last imam following Ali whom all Shi’a sub-branches mutually recognize. The Battle of Karbala is often cited as the break between the Shi’a and Sunni sects of Islam, and is commemorated each year by Shi’a Muslims on the Day of Ashura.

Imamate Of The Ahl al-Bay

Most of the early Shi’a differed only marginally from mainstream Sunnis in their views on political leadership, but it is possible in this sect to see a refinement of Shi’a doctrine. Early Sunnis traditionally held that the political leader must come from the tribe of Muhammad —namely, the Quraysh tribe. The Zaydis narrowed the political claims of Ali’s supporters, claiming that not just any descendant of Ali would be eligible to lead the Muslim community (ummah) but only those males directly descended from Muhammad through the union of Ali and Fatimah. But during the Abbasid revolts, other Shi’a, who came to be known as Imamiyyah (followers of the Imams), followed the theological school of Imam Ja’far al-Sadiq, himself the great great grandson of Muhammad’s son-in-law Imam Ali. They asserted a more exalted religious role for Imams and insisted that, at any given time, whether in power or not, a single male descendant of Ali and Fatimah was the divinely appointed Imam and the sole authority, in his time, on all matters of faith and law. To those Shi’a, love of the Imams and of their persecuted cause became as important as belief in Allah’s oneness and the mission of Muhammad.

Later most of the Shi’a, including Twelver and Ismaili, became Imamis. Imami Shi’a believe that Imams are the spiritual and political successors to Muhammad. Imams are human individuals who not only rule over the community with justice, but also are able to keep and interpret the divine law and its esoteric meaning. The words and deeds of Muhammad and the imams are a guide and model for the community to follow; as a result, they must be free of from error and sin, and must be chosen by divine decree, through Muhammad.

According to this view, there is always an Imam of the Age, who is the divinely appointed authority on all matters of faith and law in the Muslim community. Ali was the first imam of this line, the rightful successor to Muhammad, followed by male descendants of Muhammad through his daughter Fatimah.

This difference between following either the Ahl al-Bayt (Muhammad’s family and descendants) or Caliph Abu Bakr has shaped Shi’a and non-Shi’a views on some of the Qur’anic verses, the hadith (narrations from Muhammad) and other areas of Islam. According to Sunnis, Ali was the fourth successor to Abu Bakr, while the Shi’a maintain that Ali was the first divinely sanctioned “Imam,” or successor of Muhammad. The seminal event in Shi’a history is the martyrdom in 680 AD at the Battle of Karbala of Ali’s son Hussein ibn Ali, who led a non-allegiance movement against the defiant caliph (71 of Hussein’s followers were killed as well). Hussein came to symbolize resistance to tyranny. It is believed in Twelver and Ismaili Shi’a Islam that ‘aql, divine wisdom, was the source of the souls of the prophets and imams and gave them esoteric knowledge called ḥikmah and that their sufferings were a means of divine grace to their devotees. Although the imam was not the recipient of a divine revelation, he had a close relationship with Allah, through which Allah guides him, and the imam, in turn, guides the people. Imamate, or belief in the divine guide, is a fundamental belief in the Twelver and Ismaili Shi’a branches and is based on the concept that Allah would not leave humanity without access to divine guidance.

Imam Of The Time, Last Imam Of The Shi’a

The Mahdi is the prophesied redeemer of Islam who will rule for seven, nine or nineteen years (according to differing interpretations) before the Day of Judgment and will rid the world of evil. According to Islamic tradition, the Mahdi’s tenure will coincide with the Second Coming of Jesus Christ (Isa), who is to assist the Mahdi against the Masih ad-Dajjal (literally, the “false Messiah” or Antichrist). Jesus, who is considered the Masih (Messiah) in Islam, will descend at the point of a white arcade, east of Damascus, dressed in yellow robes with his head anointed. He will then join the Mahdi in his war against the Dajjal, where Jesus will slay Dajjal and unite mankind.

Theology

The Shi’a Islamic faith is vast and inclusive of many different groups. Shi’a theological beliefs and religious practices, such as prayers, differ slightly from the Sunnis.’ While all Muslims pray five times daily, Shi’as have the option of combining Dhuhr (the prayer just after mid-day) with Asr (the prayer of late afternoon) and Maghrib (the prayer of just after sunset) with Isha,’ (the night-time prayer and the last prayer of the day) as there are three distinct times mentioned in the Qur’an. The Sunnis tend to combine only under certain circumstances. Shi’a Islam embodies a completely independent system of religious interpretation and political authority in the Muslim world. The original Shi’a identity referred to the followers of Imam Ali, and Shi’a theology was formulated after Hijra (8th century AD). The first Shi’a governments and societies were established by the end of the 3rd 9th century AD. The 10th century AD has been referred to by Louis Massignon as “the Shi’ite Ismaili century in the history of Islam.”

Hadith

The Shi’a believe that the status of Ali is supported by numerous hadith, including the Hadith of the pond of Khumm, Hadith of the two weighty things, Hadith of the pen and paper, Hadith of the invitation of the close families, and Hadith of the Twelve Successors. In particular, the Hadith of the Cloak is often quoted to illustrate Muhammad’s feeling towards Ali and his family by both Sunni and Shi’a scholars. Shi’as prefer hadith attributed to the Ahl al-Bayt and close associates, and have their own separate collection of hadiths.

Profession Of Faith

The Shi’a version of the Shahada, the Islamic profession of faith, differs from that of the Sunni. The Sunni Shahada states, “There is no god except Allah, Muhammad is the messenger of Allah,” but to this the Shi’a append “Ali is the Wali (custodian) of Allah.” This phrase embodies the Shi’a emphasis on the inheritance of authority through Muhammad’s lineage. The three clauses of the Shi’a Shahada thus address tawhid (the unity of Allah), nubuwwah (the prophethood of Muhammad), and imamah (imamate, the leadership of the faith).

The basis of Ali as the “wali” is taken from a specific verse of the Qur’an. A more detailed discussion of this verse is available.

Infallibility

Ismah is the concept of infallibility or “divinely bestowed freedom from error and sin” in Islam. Muslims believe that Muhammad and other prophets in Islam possessed ismah. Twelver and Ismaili Shi’a Muslims also attribute the quality to Imams as well as to Fatimah, daughter of Muhammad, in contrast to the Zaidi, who do not attribute ‘ismah to the Imams. Though initially beginning as a political movement, infallibility and sinlessness of the imams later evolved as a distinct belief of (non-Zaidi) Shi’ism.

According to Shi’a theologians, infallibility is considered a rational necessary precondition for spiritual and religious guidance. They argue that since Allah has commanded absolute obedience from these figures they must only order that which is right. The state of infallibility is based on the Shi’a interpretation of the verse of purification.

Thus, they are the most pure ones, the only immaculate ones preserved from, and immune to, all uncleanness. It does not mean that supernatural powers prevent them from committing a sin, but due to the fact that they have absolute belief in Allah, they refrain from doing anything that is a sin.

They also have a complete knowledge of Allah’s will. They are in possession of all knowledge brought by the angels to the prophets (nabi) and the messengers (rasul). Their knowledge encompasses the totality of all times. They thus act without fault in religious matters. Shi’as regard Ali as the successor of Muhammad not only ruling over the community in justice, but also interpreting Islamic practices and its esoteric meaning. Hence he was regarded as being free from error and sin (infallible), and appointed by Allah by divine decree (nass) to be the first Imam. Ali is known as “perfect man” (al-insan al-kamil) similar to Muhammad, according to Shi’a viewpoint.

Occultation

The Occultation is a belief in some forms of Shi’a Islam that a messianic figure, a hidden imam known as the Mahdi, will one day return and fill the world with justice. According to the Twelver Shi’a, the main goal of Mahdi will be to establish an Islamic state and to apply Islamic laws that were revealed to Muhammad.

Some Shi’a, such as the Zaidi and Nizari Ismaili, do not believe in the idea of the Occultation. The groups which do believe in it differ as to which lineage of the Imamate is valid, and therefore which individual has gone into occultation. They believe there are many signs that will indicate the time of his return.

Twelver Shi’a Muslims believe that the Mahdi (the twelfth imam, Muhammad al-Mahdi) is already on Earth, is in occultation and will return at the end of time. Fatimid/ Bohra/ Dawoodi Bohra believe the same but for their 21st Tayyib, whereas Sunnis believe the future Mahdi has not yet arrived on Earth.

Inheritance

It is believed that the armaments and sacred items of all of the Prophets, including Muhammad, were handed down in succession to the Imams of Ahl al-Bayt. In Kitab al-Kafi, Ja’far al-Sadiq mentions that “with me are the arms of the Messenger of Allah. It is not disputable.”

Further, he claims that with him is the sword of the Messenger of Allah, his coat of arms, his Lamam (pennon – a long triangular or swallow-tailed flag, especially one of a kind formerly attached to a lance or helmet; a pennant) and his helmet. In addition, he mentions that with him is the flag of the Messenger of Allah, the victorious. With him is the Staff of Moses, the ring of Solomon, son of David, and the tray on which Moses used to offer his offerings. With him is the name that whenever the Messenger of Allah would place it between the Muslims and pagans no arrow from the pagans would reach the Muslims. With him is the similar object that angels brought.

Al-Sadiq also narrates that the passing down of armaments is synonymous to receiving the Imamat (leadership), similar to how the Ark in the house of the Israelites signaled prophet-hood.

Imam Ali al-Ridha narrates that wherever the armaments among us would go, knowledge would also follow and the armaments would never depart from those with knowledge (Imamat).

History

Historians dispute the origin of Shi’a Islam, with many Western scholars positing that Shi’ism began as a political faction rather than a truly religious movement. Other scholars disagree, considering this concept of religious-political separation to be an anachronistic application of a Western concept.

Following the Battle of Karbala (680 AD), as various Shi’a-affiliated groups diffused in the emerging Islamic world, several nations arose based on a Shi’a leadership or population.

- Idrisids (788 to 985 AD): a Zaydi dynasty in what is now Morocco;

- Uqaylids (990 to 1096 AD): a Shi’a Arab dynasty with several lines that ruled in various parts of Al-Jazira, northern Syria and Iraq;

- Buyids (934–1055 AD): at its peak consisted of large portions of modern Iraq and Iran;

- Ilkhanate (1256–1335): a Mongol khanate established in Persia in the 13th century, considered a part of the Mongol Empire. The Ilkhanate was based, originally, on Genghis Khan’s campaigns in the Khwarezmid Empire in 1219–1224, and founded by Genghis’s grandson, Hulagu, in territories which today comprise most of Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Turkey, and Pakistan. The Ilkhanate initially embraced many religions, but was particularly sympathetic to Buddhism and Christianity. Later Ilkhanate rulers, beginning with Ghazan in 1295, embraced Islam his brother Öljaitü promoted Shi’a Islam;

- Naubat Khan accepted Islam under the Guidance of Mughal General Bairam Khan’s son Abdul Rahim Khan-I-Khana;

- Bahmanis (1347–1527 AD): a Shi’a Muslim state of the Deccan in southern India and one of the great medieval Indian kingdoms. Bahmanid Sultanate was the first independent Islamic Kingdom in South India.

North Africa

- Idrisid dynasty (780–985 AD) — Zaidi;

- Fatimid Caliphate (909–1171 AD) — Ismaili;

- Banu Kanz (1004–1412 AD).

Iran and Caucasus

- Justanids (791–974 AD) — Zaidi;

- Alavids (864–929 AD) — Zaidi;

- Aishanids (912–961 AD);

- Ziyarid dynasty (928–1043 AD);

- Buyid dynasty (934–1062 AD) — Zaidi, later converted to Twelver;

- Hasanwayhid (959–1015 AD);Kakuyids (1008–1051 AD);

- Nizari Ismaili state (1090–1256 AD) — Nizar;

- Sarbadars (1332–1386 AD) — Twelver;

- Injuids (1335–1357 AD) — Twelver;

- Marashiyan (1359–1582 AD);

- Kara Koyunlu (1375–1468 AD);

- Musha’sha’iyyah dynasty (1436–1729 AD) — Musha’sha’iyyah;

- Safavid dynasty (1501–17;

- Bakuq Khanate (1753–1806 AD);

- Erivan Khanate (1604–1828 AD);

- Derbent Khanate (1747–1806 AD);

- Ganja Khanate (1747–1804 AD);

- Javad Khanate (1747-1805 AD);

- Talysh Khanate (1747–1828 AD;

- Nakhichevan Khanate (1747–1813 AD);

- Karabakh Khanate (1747–1822 AD);

- Qajar dynasty (1785–1925 AD);

- Pahlavi dynasty (1925–1979 AD).

Arabian Peninsula

Bahrain

- Qarmatians (900–1073 AD) — Qarmatians;\~

- Uyunid dynasty (1073-1253 AD) — Twelver;

- Usfurids (1253–1320 AD) — Twelver;

- ZJarwanid dynasty (1305–1487 AD) — Ismaili and Twelver;

- Jabrids (15/16th century) — Twelver;

- Banu Ukhaidhir (865–1066 AD) — Zaidi;

- Rassids (893–1970 AD) — Zaidi;

- Sulaihid State (1047–1138 AD) — Ismaili;

- Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen (1926–1970 AD) — Zaidi.

Europe

- Kalbids (948–1053 AD);

- Hammudid

- dynasty (1016–1073 AD) — Zaidi

Syria and Iraq

- Hamdanid dynasty (890–1004 AD);

- Bani Assad (961–1163 AD) (central and southern Iraq);

- Numayrids (990–1081 AD) (eastern Syria and southeastern Turkey);

- Marwanids (990–1085 AD);

- Uqaylid Dynasty (990–1169 AD);

- Mirdasids (1024–1080 AD).

Asia Minor (Modern Turkey)

- Eretnids (1328–1381 AD);

- Danishmends (1071–1178 AD);

- Beylik of Erzincan (1379–1410 AD).

India

- Bahmani Sultanate (1347–1527 AD);

- Jaunpur Sultanate (1394–1479 AD);

- Bidar Sultanate (1489–1619 AD);

- Berar Sultanate (1490–1572 AD);

- Ahmadnagar Sultanate (1490–1636 AD);

- Qutb Shahi dynasty (1512–1687 AD);

- Adil Shahi dynasty (1490–1686 AD);

- Najm-i-Sani dynasty (1658–? AD);

- Nawab of Rampur (1719–1949 AD);

- Nawabs of Oudh (1722–1858 AD);

- Nawabs of Beng Talpur dynasty (1783–1843 AD);

- Hunza (princely state) (1500s—1974 AD);

- Nagar (princely state) (14th Century—1974 AD).

South-East Asia

- Daya Pasai (1128–1285 AD);

- Bandar Kalibah;

- Moira Malaya;

- Kanto Kambar;

- Robaromun.

- Kilwa Fatimids (909–1171 AD): Controlled much of North Africa, the Levant, parts of Arabia and Mecca and Medina. The group takes its name from Fatima, Muhammad’s daughter, from whom they claim descent.

In 909 AD the Shi’ite military leader Abu Abdallah, overthrew the Sunni ruler in Northern Africa; which began the Fatimid regime.

Safavids

One of Shah Ismail I of Safavid dynasty first actions, was the proclamation of the Twelver sect of Shi’a Islam to be the official religion of his newly formed state. Causing sectarian tensions in the Middle East when he destroyed the tombs of Abū Ḥanīfa and the Sufi Abdul Qadir Gilani in 1508. In 1533, Ottomans, upon their conquest of Iraq, rebuilt various important Sunni shrines.

A major turning point in Shi’a history was the Safavid dynasty (1501–1736) in Persia. This caused a number of changes in the Muslim world:

- The ending of the relative mutual tolerance between Sunnis and Shi’as that existed from the time of the Mongol conquests onwards and the resurgence of antagonism between the two groups.

- Initial dependence of Shi’ite clerics on the state followed by the emergence of an independent body of ulama capable of taking a political stand different from official policies.

- The growth in importance of Iranian centers of religious learning and change from Twelver Shi’ism being a predominantly Arab phenomenon.

- The growth of the Akhbari School which preached that only the Qur’an, hadith are to be basis for verdicts, rejecting the use of reasoning.

With the fall of the Safavids, the state in Persia – including the state system of courts with government-appointed judges (qadis) – became much weaker. This gave the Shari’a courts of mujtahids an opportunity to fill the legal vacuum and enabled the ulama to assert their judicial authority. The Usuli School also increased in strength at this time.

Community

Demographics

According to Shi’a Muslims, one of the lingering problems in estimating Shi’a population is that unless Shi’a form a significant minority in a Muslim country, the entire population is often listed as Sunni. The reverse, however, has not held true, which may contribute to imprecise estimates of the size of each sect. For example, the 1926 rise of the House of Saud in Arabia brought official discrimination against Shi’a. Shi’ites are estimated to be 21–35 percent of the Muslim population in South Asia, although the total number is difficult to estimate due to that reason. It is variously estimated that 10–20 percent of the world’s Muslims are Shi’a. They may number up to 200 million as of 2009.

The Shi’a majority countries are Iran, Iraq, Azerbaijan, and Bahrain. They also form the plurality (the largest group, but not the majority) in Lebanon. Shi’as constitute 36.3 percent of entire local population and 38.6 percent of the local Muslim population of the Middle East.

Shi’a Muslims constitute 27-35 percent of the population in Lebanon, and as per some estimates from 35 percent to over 35–40 percent of the population in Yemen, 30 percent to 35 percent of the citizen population in Kuwait (no figures exist for the non-citizen population), over 20 percent in Turkey, 5–20 percent of the population in Pakistan, and 10–19 percent of Afghanistan’s population.

Saudi Arabia hosts a number of distinct Shi’a communities, including the Twelver Baharna (the Baharna are a Shia Muslim ethnoreligious group who mainly inhabit the historical region of Eastern Arabia) in the Eastern Province and Nakhawila of Medina, and the Ismaili Sulaymani and Zaidiyyah of Najran. Estimations put the number of Shi’ite citizens at 2–4 million, accounting for roughly 15 percent of the local population.

Significant Shi’a communities exist in the coastal regions of West Sumatra and Aceh in Indonesia. The Shi’a presence is negligible elsewhere in Southeast Asia, where Muslims are predominantly Shafi’i Sunnis.

A significant Shi’a minority is present in Nigeria, made up of modern-era converts to a Shi’a movement centered around Kano and Sokoto states. Several African countries like Kenya, South Africa, Somalia, etc., hold small minority populations of various Shi’a denominations, primarily descendants of immigrants from South Asia during the colonial period, such as the Khoja (the Khojas are a caste of people originating in India).

Significant Populations Worldwide

Distribution of global Shi’a Muslim population among the continents:

- Asia (93.3 percent)

- Africa (4.4 percent)

- Europe (1.5 percent)

- Americas (0.7 percent)

- Australia (0.1 percent)

Persecution

The history of Sunni-Shi’a relations has often involved violence, dating back to the earliest development of the two competing sects. At various times Shi’a groups have faced persecution.

Militarily established and holding control over the Umayyad government, many Sunni rulers perceived the Shi’a as a threat – to both their political and their religious authority. The Sunni rulers under the Umayyads sought to marginalize the Shi’a minority, and later the Abbasids turned on their Shi’a allies and imprisoned, persecuted, and killed them. The persecution of the Shi’a throughout history by Sunni co-religionists has often been characterized by brutal and genocidal acts. Comprising only about 10–15 percent of the entire Muslim population, the Shi’a remain a marginalized community to this day in many Sunni Arab dominant countries without the rights to practice their religion and organize.

In 1514 the Ottoman sultan, Selim I, ordered the massacre of 40,000 Anatolian Shi’a. Sultan Selim I carried things so far that he announced that the killing of one Shi’ite had as much otherworldly reward as killing 70 Christians.

In 1801 the Al Saud-Wahhabi armies attacked and sacked Karbala, the Shi’a shrine in eastern Iraq that commemorates the death of Husayn.

Under Saddam Hussein’s regime, 1968 to 2003, in Iraq, Shi’a Muslims were heavily arrested, tortured and killed.

In March 2011, the Malaysian government declared the Shi’a a “deviant” sect and banned them from promoting their faith to other Muslims, but left them free to practice it themselves privately.

Holidays

Shi’a, celebrate the following annual holidays:

- Eid ul-Fitr, which marks the end of fasting during the month of Ramadan;

- Eid al-Adha, which marks the end of the Hajj or pilgrimage to Mecca;

- The following days are some of the most important holidays observed by Shi’a Muslims:

Eid al-Ghadeer, which is the anniversary of the Ghadir Khum, the occasion when Muhammad announced Ali’s Imamate before a multitude of Muslims. Eid al-Ghadeer is held on the 18th of Dhu al-Hijjah.

The Mourning of Muharram and the Day of Ashura for Shi’a commemorates Husayn ibn Ali’s martyrdom. Husayn was a grandson of Muhammad who was killed by Yazid ibn Muawiyah. Ashurah is a day of deep mourning which occurs on the 10th of Muharram.

Arba’een commemorates the suffering of the women and children of Husayn ibn Ali’s household. After Husayn was killed, they were marched over the desert, from Karbala (central Iraq) to Shaam (Damascus, Syria). Many children (some of whom were direct descendants of Muhammad) died of thirst and exposure along the route. Arbaein occurs on the 20th of Safar (the second month of the Islamic calendar), 40 days after Ashurah (the tenth day of Muḥarram, the first month in the Islamic calendar).

Mawlid, Muhammad’s birth date. Unlike Sunni Muslims, who celebrate the 12th of Rabi’ al-awwal as Muhammad’s birthday or deathday (because they assert that his birth and death both occur in this week), Shi’a Muslims celebrate Muhammad’s birthday on the 17th of the month, which coincides with the birth date of the sixth imam, Ja’far al-Saadiq. Wahhabis do not celebrate Muhammad’s birthday, believing that such celebrations constitute a bid‘ah (heresy in religious matters).

Fatimah’s birthday on 20th of Jumada al-Thani. This day is also considered as the “‘women and mothers’ day.”

Ali’s birthday on 13th of Rajab.

Mid-Sha’ban is the birth date of the 12th and final Twelver imam, Muhammad al-Mahdi. It is celebrated by Shi’a Muslims on the 15th of Sha’aban.

Laylat al-Qadr, anniversary of the night of the revelation of the Qur’an.

Eid al-Mubahila celebrates a meeting between the Ahl al-Bayt (household of Muhammad) and a Christian deputation from Najran. Al-Mubahila is held on the 24th of Dhu al-Hijjah.

Holy Sites

The four holiest sites to Muslims are:

- Mecca (Al-Haram Mosque);

- Medina (Al-Nabbawi Mosque);

- Jerusalem (Al-Aqsa Mosque); and ,

- Kufa (Kufa Mosque).

In addition for Shi’as, these are also highly revered:

Imam Ali Mosque in Najaf.

Other venerated sites include:

- Wadi-us-Salaam cemetery in Najaf;

- Al-Baqi’ cemetery in Medina;

- Imam Reza shrine in Mashhad;

- Kadhimiya Mosque in Kadhimiya;

- Al-Askari Mosque in Samarra;

- Sahla Mosque;

- Great Mosque of Kufa

- Several other sites in the cities of Qom, Susa and Damascus.

Most of the Shi’a holy places in Saudi Arabia have been destroyed by the warriors of the Ikhwan, the most notable being the tombs of the Imams in the Al-Baqi’ cemetery in 1925.M In 2006, a bomb destroyed the shrine of Al-Askari Mosque.

Branches

The Shi’a belief throughout its history split over the issue of the Imamate. The largest branch are the Twelvers, followed by the Zaidi and Ismaili. All three groups follow a different line of Imamate.

(It may help to print this out and use as a reference for what follows – I had to use it just to write it. (editors)

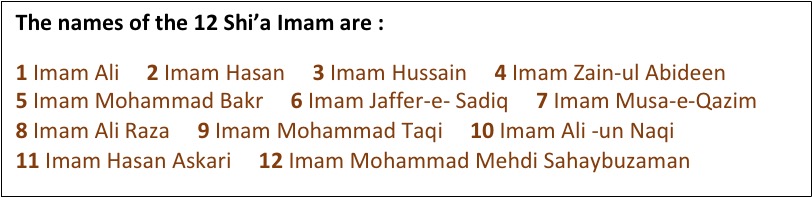

Twelver

Twelver Shi’a or the Ithnā’ashariyyah’ is the largest branch of Shi’a Islam, and the term Shi’a Muslim often refers to the Twelvers by default. The term Twelver is derived from the doctrine of believing in twelve divinely ordained leaders, known as The Twelve Imams. Twelver Shi’a are also known as Imami or Ja’fari, originated from the name of the 6th Imam, Ja’far al-Sadiq, who elaborated the twelver jurisprudence.

`Twelvers constitute the majority of the population in Iran (90 percent of Muslims), Azerbaijan (85 percent of Muslims), Bahrain (70 percent of Muslims), Iraq (65 Percent Muslims), Lebanon (65 percent of Muslims).

Doctrine

| The names of the 12 Shi’a Imam are : 1 Imam Ali 2 Imam Hasan 3 Imam Hussain 4 Imam Zain-ul Abideen5 Imam Mohammad Bakr 6 Imam Jaffer-e- Sadiq 7 Imam Musa-e-Qazim8 Imam Ali Raza 9 Imam Mohammad Taqi 10 Imam Ali -un Naqi11 Imam Hasan Askari 12 Imam Mohammad Mehdi Sahaybuzaman |

Twelver doctrine is based on five principles. These five principles known as Usul ad-Din are as follow:

- Monotheism, Allah is one and unique;

- Justice, the concept of moral rightness based on ethics, fairness, and equity, along with the punishment of the breach of said ethics;

- Prophethood, the institution by which Allah sends emissaries, or prophets, to guide mankind;

- Leadership, a divine institution which succeeded the institution of Prophethood. Its appointees (imams) are divinely appointed;

- Last Judgment, Allah’s final assessment of humanity.

More specifically, these principles are known as Usul al-Madhhab (principles of the Shi’a sect) according to Twelver Shi’as which differ from Daruriyat al-Din (Necessities of Religion) which are principles in order for one to be a Muslim. The Necessities of Religion do not include Leadership (Imamah) as it is not a requirement in order for one to be recognized as a Muslim. However, this category, according to Twelver scholars like Ayatollah al-Khoei, does include belief in Allah, Prophethood, the Day of Resurrection and other “necessities” (like belief in angels). In this regard, Twelver Shi’as draw a distinction in terms of believing in the main principles of Islam on the one hand, and specifically Shi’a doctrines like Imamah on the other.

Book

Besides the Qur’an which is common to all Muslims, the Shi’ah derive guidance from books of traditions (“ḥadīth”) attributed to Muhammad and the Twelve Imams. Below is a list of some of the most prominent of these books:

- Nahjâ al-Balagha by Ali ibn Abi Talib – the most famous collection of sermons, letters & narration by the first Imam regarded by Shi’as;

- al-Kafi by Muhammad ibn Ya’qub al3-Kulayni;

- Wasa’il al-Shi’ah by al-Hurr al-Amili;

- The Twelve Imams; See also: The Twelve Imams and Sunni reports about there being 12 successors to the Prophet;

The Twelve Imams are the spiritual and political successors to Muhammad for the Twelvers. According to the theology of Twelvers, the successor of Muhammad is an infallible human individual who not only rules over the community with justice but also is able to keep and interpret the divine law and its esoteric meaning. The words and deeds of Muhammad and the imams are a guide and model for the community to follow; as a result, they must be free from error and sin, and Imams must be chosen by divine decree, through Muhammad. Each imam was the son of the previous imam, with the exception of Hussein ibn Ali, who was the brother of Hasan ibn Ali. The twelfth and final imam is Muhammad al-Mahdi, who is believed by the Twelvers to be currently alive and in occultation.

Jurisprudence

The Twelver jurisprudence is called Ja’fari jurisprudence. In this jurisprudence, Sunnah is considered to be the oral traditions of Muhammad and their implementation and interpretation by the twelve Imams. There are three schools of Ja’fari jurisprudence: Usuli, Akhbari, and Shaykhi. The Usuli school is by far the largest of the three. Twelver groups that do not follow Ja’fari jurisprudence include Alevi, Bektashi, and Qizilbash.The five primary pillars of Islam to the Ja’fari jurisprudence, known as Usul’ ad-Din, are at variance with the standard Sunni “five pillars of religion.” The Shi’as’ primary “pillars” are:

- Tawhid or oneness of Allah;

- Nabuwa prophet;

- Mu’ad resurrection;

- Adl justice (of Allah);

- Imama the rightful place of the Shi’a Imams.

In Ja’fari jurisprudence, there are eight secondary pillars, known as Furu’ ad-Din, which are as follows:

- Prayer;

- Fasting;

- Pilgrimage to Mecca

- Alms giving

- Struggle for the righteous cause

- Directing others towards good

- Directing others away from evil

- Khums) (20 percent tax on yearly business earnings after deduction of commercial expenses.)

According to Twelvers, defining and interpretation of Islamic jurisprudence is the responsibility of Muhammad and the twelve Imams. As the 12th Imam is in occultation, it is the duty of clerics to refer to the Islamic literature such as the Qur’an and hadith and identify legal decisions within the confines of Islamic law to provide means to deal with current issues from an Islamic perspective. In other words, Twelver clerics provide Guardianship of the Islamic Jurisprudence, which was defined by Muhammad and his twelve successors. This process is known as Ijtihad and the clerics are known as Marja,’ meaning reference. The labels Allamah and Ayatollah are in use for Twelver clerics.

Zaidi (“Fiver”)

Zaidiyya, Zaidism or Zaydi is a Shi’a school named after Zayd ibn Ali. Followers of the Zaidi fiqh are called Zaidis (or occasionally Fivers). However, there is also a group called Zaidi Wasītīs who are Twelvers (see below). Zaidis constitute roughly 42–47 percent of the population of Yemen.

Doctrine

The Zaydis, Twelvers, and Ismailis all recognize the same first four Imams; however, the Zaidis recognize Zayd ibn Ali as the fifth. After the time of Zayd ibn Ali, the Zaidis recognized that any descendant of Hasan ibn Ali or Hussein ibn Ali could be imam after fulfilling certain conditions. Other well-known Zaidi Imams in history were Yahya ibn Zayd, Muhammad al-Nafs al-Zakiyya and Ibrahim ibn Abdullah.

The Zaidi doctrine of Imamah does not presuppose the infallibility of the imam nor that the Imams receive divine guidance. Zaidis also do not believe that the Imamate must pass from father to son but believe it can be held by any Sayyid descended from either Hasan ibn Ali or Hussein ibn Ali (as was the case after the death of Hasan ibn Ali). Historically, Zaidis held that Zayd was the rightful successor of the 4th imam since he led a rebellion against the Umayyads in protest of their tyranny and corruption. Muhammad al-Baqir did not engage in political action, and the followers of Zayd believed that a true imam must fight against corrupt rulers.

Jurisprudence

In matters of Islamic jurisprudence, the Zaydis follow Zayd ibn Ali’s teachings which are documented in his book Majmu’l Fiqh. Al-Hadi ila’l-Haqq Yahya, founder of the Zaydi state in Yemen, instituted elements of the jurisprudential tradition of the Sunni Muslim jurist Abū Ḥanīfa, and as a result, Zaydi jurisprudence today continues somewhat parallel to that of the Hanafis.

Timeline

The Idrisids were Arab Zaydi Shi’a dynasty in the western Maghreb ruling from 788 to 985 AD, named after its first sultan, Idris I.

A Zaydi state was established in Gilan, Deylaman and Tabaristan (northern Iran) in 864 AD by the Alavids; it lasted until the death of its leader at the hand of the Samanids in 928 AD Roughly forty years later the state was revived in Gilan and survived under Hasanid leaders until 1126 AD. Afterwards, from the 12th to 13th centuries, the Zaydis of Deylaman, Gilan and Tabaristan then acknowledged the Zaydi Imams of Yemen or rival Zaydi Imams within Iran.

The Buyids were initially Zaidi as were the Banu Ukhaidhir rulers of al-Yamama in the 9th and 10thcenturies. The leader of the Zaydi community took the title of Caliph. As such, the ruler of Yemen was known as the Caliph, al-Hadi Yahya bin al-Hussain bin al-Qasim ar-Rassi Rassids (a descendant of Hasan ibn Ali the son of Ali) who, at Sa’dah, in 893–897 AD, founded the Zaydi Imamate, and this system continued until the middle of the 20th century, when the revolution of 1962 AD deposed the Zaydi Imam. The founding Zaidism of Yemen was of the Jarudiyya group; however, with increasing interaction with Hanafi and Shafi’i rites of Sunni Islam, there was a shift from the Jarudiyya group to the Sulaimaniyya, Tabiriyya, Butriyya or Salihiyya groups. Zaidis form the second dominant religious group in Yemen. Currently, they constitute about 40–45 percent of the population in Yemen. Ja’faris and Isma’ilis are 2–5 percent. In Saudi Arabia, it is estimated that there are over 1 million Zaydis (primarily in the western provinces).

Currently the most prominent Zaydi movement is the Houthis movement, known by the name of Shabab Al Mu’mineen (Believing Youth) or AnsarAllah (Partisans of Allah). In 2014–2015 Houthis took over the government in Sana’a, which led to the fall of the Saudi Arabian-backed government of Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi. Houthis and their allies gained control of a significant part of Yemen’s territory and were resisting the Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen seeking to restore Hadi in power. Both the Houthis and the Saudi Arabian-led coalition were being attacked by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant.

Ismaili

Ismailis gain their name from their acceptance of Isma’il ibn Jafar as the divinely appointed spiritual successor (Imam) to Ja’far al-Sadiq, wherein they differ from the Twelvers, who accept Musa al-Kadhim, younger brother of Isma’il, as the true Imam.

After the death or Occultation of Muhammad ibn Ismaill in the 8th century, the teachings of Ismailism further transformed into the belief system as it is known today, with an explicit concentration on the deeper, esoteric meaning (bāṭin) of the faith. With the eventual development of Twelverism into the more literalistic (zahir) oriented Akhbari and later Usuli schools of thought, Shi’aism developed in two separate directions: the metaphorical Ismailli group focusing on the mystical path and nature of Allah and the divine manifestation in the personage of the “Imam of the Time” as the “Face of Allah,” with the more literalistic Twelver group focusing on divine law (sharī’a) and the deeds and sayings (sunnah) of Muhammad and his successors (the Ahlu l-Bayt), who as A’immah were guides and a light to Allah.

Though there are several sub-groupings within the Ismailis, the term in today’s vernacular generally refers to The Shi’a Imami Ismaili Muslim (Nizari community), generally known as the Ismailis, who are followers of the Aga Khan and the largest group among the Ismailiyyah. Another community which falls under the Isma’il’s are the Dawoodi Bohras, led by a Da’i al-Mutlaq as representative of a hidden imam. While there are many other branches with extremely differing exterior practices, much of the spiritual theology has remained the same since the days of the faith’s early Imams. In recent centuries Ismailis have largely been an Indo-Iranian community, but they are found in India, Pakistan, Syria, Palestine, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, China, Jordan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, East Africa and South Africa, and have in recent years emigrated to Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and North America.

Ismaili Imams

After the death of Isma’il ibn Jafar, many Ismailis believed that one day the messianic Mahdi, whom they believed to be Muhammad ibn Ismail, would return and establish an age of justice. One group included the violent Qarmatians, who had a stronghold in Bahrain. In contrast, some Ismailis believed the Imamate did continue, and that the Imams were in occultation and still communicated and taught their followers through a network of dawah “Missionaries.”

In 909, Abdullah al-Mahdi Billah, a claimant to the Ismaili Imamate, established the Fatimid Caliphate. During this period, three lineages of imams formed. The first branch, known today as the Druze, began with Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah. Born in 985 AD, he ascended as ruler at the age of eleven. The typical religiously tolerant Fatimid Empire saw much persecution under his reign. When in 1021 AD his mule returned without him, soaked in blood, a religious group that was forming in his lifetime broke off from mainstream Ismailism and did not acknowledge his successor. Later to be known as the Druze, they believe al-Hakim to be the incarnation of Allah and the prophesied Mahdi who would one day return and bring justice to the world. The faith further split from Ismailism as it developed very unusual doctrines which often class it separately from both Ismailiyyah and Islam.

The second split occurred following the death of Ma’ad al-Mustansir Billah in 1094 AD. His rule was the longest of any caliph in any Islamic empire. Upon his passing away, his sons, Nizar the older, and Al-Musta’li, the younger, fought for political and spiritual control of the dynasty. Nizar was defeated and jailed, but according to Nizari tradition, his son escaped to Alamut, where the Iranian Ismaili had accepted his claim. From here on, the Nizari Ismaili community has continued with a present, living Imam.

The Mustaali line split again between the Taiyabi (Dawoodi Bohra is its main branch) and the Hafizi. The former claim that At-Tayyib Abi l-Qasim (son of Al-Amir bi-Ahkami l-Lah) and the imams following him went into a period of anonymity (Dawr-e-Satr) and appointed a Da’i al-Mutlaq to guide the community, in a similar manner as the Ismaili had lived after the death of Muhammad ibn Ismail. The latter (Hafizi) claimed that the ruling Fatimid Caliph was the Imam, and they died out with the fall of the Fatimid Empire.

Pillars

Ismailis have categorized their practices which are known as seven pillars:

- Walayah (Guardianship)

- Taharah (Purity)

- Salat (Prayer)

- Zakāt (Charity)

- Sawm (Fasting)

- Hajj (Pilgrimage)

- Jihad (Struggle)

The Shahada (profession of faith) of the Shi’a differs from that of Sunnis due to mention of Ali.

Contemporary Leadership

The Nizaris place importance on a scholarly institution because of the existence of a present Imam. The Imam of the Age defines the jurisprudence, and his guidance may differ with Imams previous to him because of different times and circumstances. For Nizari Ismailis, the Imam is Karim al-Husayni Aga Khan IV. The Nizari line of Imams has continued to this day as an unending line.

Divine leadership has continued in the Bohra branch through the institution of the “Unrestricted Missionary” Dai. According to Bohra tradition, before the last Imam, At-Tayyib Abi l-Qasim, went into seclusion, his father, the 20th Al-Amir bi-Ahkami l-Lah, had instructed Al-Hurra Al-Malika the Malika (Queen consort) in Yemen to appoint a vicegerent after the seclusion – the Unrestricted Missionary, who as the Imam’s vicegerent has full authority to govern the community in all matters both spiritual and temporal while the lineage of Mustaali-Tayyibi Imams remains in seclusion (Dawr-e-Satr). The three branches of the Mustaali, the Alavi Bohra, Sulaimani Bohra and Dawoodi Bohra, differ on who the current Unrestricted Missionary is.

Other Doctrines

According to Allameh Muzaffar, Allah gives humans the faculty of reason and argument. Also, Allah orders humans to spend time thinking carefully on creation while he refers to all creations as his signs of power and glory. These signs encompass all of the universe. Furthermore, there is a similarity between humans as the little world and the universe as the large world. Allah does not accept the faith of those who follow him without thinking and only with imitation, but also Allah blames them for such actions. In other words, humans have to think about the universe with reason and intellect, a faculty bestowed by Allah. Since there is more insistence on the faculty of intellect among Shi’a, even evaluating the claims of someone who claims prophecy is on the basis of intellect.

Doctrine Concerning Du’a

Praying or Du’a in Shi’a has an important place as Muhammad described it as a weapon of the believer. In fact, Du’a considered as something that is a feature of Shi’a community in a sense. Performing Du’a in Shi’a has a special ritual. Because of this, there are many books written on the conditions of praying among Shi’a. Most of ad’ayieh transferred from Muhammad’s household and then by many books in which we can observe the authentic teachings of Muhammad and his household according to Shi’a. The leaderships of Shi’a always invited their followers to recite Du’a. For instance, Ali has considered with the subject of Du’a because of his leadership in monotheism.

Shīʿī Islam

Historical Overview

The term Shīʿah literally means followers, party, group, associate, partisan, or supporters. Expressing these meanings, Shīʿah occurs a number of times in the Qurʿān (e.g., surahs 19:69, 28:15, and 37:83). Technically the term refers to those Muslims who derive their religious code and spiritual inspiration, after the Prophet, from Muḥammad’s descendants, the ahl al-bayt (literally, people of the house). The focal point of Shi’ism is the source of religious guidance after the Prophet; although the Sunnīs accept it from the ṣaḥābah (companions) of the Prophet, the Shīʿah restrict it to the members of the ahl al-bayt. This pivotal point is based on two important factors, one sociocultural and the other drawn from the Qurʿānic concept of the exalted and virtuous nature of the prophetic families.

To understand the sociocultural factor we must keep in mind the nature and composition of the Muslim community at Medina under the leadership of the prophet Muḥammad. This community was homogeneous in neither its sociocultural background and traditions nor its political-social institutions. The formation of a religious community, the ummah, under a new religio-moral impulse, left substantially unchanged some of the deeply rooted tribal values and traditions. It was therefore natural that some of these tribal inclinations would be reflected in certain aspects of the new religious order.

The two main constituent groups of the ummah at the time of the Prophet’s death at Medina in 632 AD were the Arabs of northern and central Arabia, of whom the Quraysh of Mecca was the dominant tribe, and the people of south Arabian origin, whose two major branches, the Aws and Khazraj, had settled at Medina. The Arabs of north and central Arabia developed along different lines from the southern Arabs of Yemen in character, way of life, profession, and sociopolitical and sociocultural institutions. More importantly, the two groups differed widely from each other in religious sensibility and feelings. Among the people of the south there was a clear predominance of religious ideas, whereas among the people of the north religious sentiments were not so strong.

This difference in religious sentiments was naturally reflected in patterns of tribal leadership. The chief or shaykh in the north had always been elected by seniority in age and ability in leadership. There might sometimes be some other considerations, such as nobility and lineal prestige, but these were of little importance in the north. The Arabs in the south, on the other hand, were accustomed to succession based on hereditary sanctity and divine rights. Also important was the nature and character of Islam in seventh-century Arabia. Islam has been both a religious discipline and a sociopolitical movement. Muḥammad, the messenger of Allah, was also the founder of the new polity in Medina. The Prophet thus left a political legacy as well as a religious heritagThe manner of choosing a successor to the Prophet thus came to involve the vision of the leadership of the Muslim community, with different approaches to and varying degrees of emphasis on its political and religious aspects. The majority of Muḥammad’s companions, with their northern Arabian background, believed the function of his successor was to safeguard the community’s political character and propagate the message of Islam beyond Arabia. Others, fewer and primarily of southern Arabian origin, conceived the succession in terms of Muḥammad’s spiritual authority. They believed that the divine guidance had to continue through his successors, who should combine in themselves the Prophet’s religious as well as temporal functions. Such leaders were the imams, who inherited the mantle of the Prophet in providing the revealed guidance for the creation of the Islamic order.

Besides these sociocultural traditions, the Qurʿānic concept of the exalted position of the prophetic families played a significant role in defining the succession. The Qurʿān describes the prophets as particularly concerned with ensuring that the special favor of Allah bestowed on them for the guidance of people be maintained in their families and be inherited by their descendants. Thus, Abraham prays to Allah to continue his guidance and special favor in his (Abrahamʿs) descendants so that His divine purposes would continue to be fulfilled. The Qurʿān refers to prophetic progeny with four key terms:

- dhurrīyah (direct descendant);

- āl (offspring; house, dynasty);

- ahl (family, progeny); and,

- qurbā (relation, nearest of kin).

When these words are used with reference to the Prophet, the commentators of the Qurʿān have interpreted them as meaning Muḥammad’s 1nearest of kin: his cousin and son-in-law ʿAlī, his daughter Fāṭimah, and their sons Ḥasan and Ḥusayn. The Shīʿah also extend the status of ahl al-bayt to the descendants of Ḥasan and Ḥusayn.

Rashidun Period

Taking into account these factors, the origin of the Shīʿa movement can be traced to the Medinan period of the Prophet’s life. Some prominent Companions saw the Prophet’s cousin ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib as his waṣī (legatee) and the imam to lead the community after him. Soon after the death of the prophet, at the beginning of the Rāshidūn period (632–661), this special regard for ʿAlī found expression when he was denied the leadership of the community. The early supporters of ʿAlī constituted the first nucleus of the Shīʿa.

However, after the initial defeat of ʿAlī’s supporters and his own recognition of Abū Bakr’s administration six months later, Shīʿa tendencies lost most of their open and active manifestations. This lasted through the caliphates of Abū Bakr and his successor, ʿUmar (r. 632–644). After the death of ʿUmar, Shīʿa feelings once again found expression in the protest made by ʿAlī’s supporters when ʿUthmān was declared the third caliph. The office was first offered to ʿAlī on the condition that he follow the precedents established by the first two caliphs; ʿAlī refused this condition, and ʿUthmān accepted it. If ideological differences between the Shīʿa and Sunnīs date back to the election of Abū Bakr, the differences in legal matters, at least theoretically, must be dated from ʿAlī’s refusal to follow the precedents of the first two caliphs. This refusal was thus a cornerstone in the development of Sh’ī legal thought, which would come to include a variety of forms (including Ithnā ʿAsharī [or Twelver], Ismāʿīlī, and Zaydī), although it took some time for the Sunnī and Shī’ī legal systems to become clearly distinguishable.

Socioeconomic issues also played a part in the development of Shīʿī Islam. Unlike the first two caliphs, ʿUthmān belonged to the powerful clan of the Umayyads which, in his accession, found an opportunity to regain its former political importance. Within a few years of ʿUthmān’s accession, the Umayyads claimed all the positions of power and advantage and appropriated to themselves the immense wealth of the empire at the expense of the masses. The resulting social and economic disequilibrium aroused the resentment of various sectors of the population. The discontent exploded into revolt, and the caliph was killed in 656. Populist opposition to the Umayyad aristocracy thus became involved with support for ʿAlī, who accepted the caliphate, reportedly with great reluctance. ʿAlī’s accession was, however, strongly resisted by the Umayyads, represented by Muʿāwiyah and some of the Companions who sought the position for themselves. This resulted in the first civil wars in Islam and ultimately led to ʿAlī’s assassination in 661.

The sixteen-year period beginning with the caliphate of ʿUthmān and ending with the assassination of ʿAlī differed markedly from the preceding period in the development of Shi’ism in a number of ways: it encouraged the Shīʿī tendencies to become more conspicuous, active, and sometimes violent, and a number of political, geographical, and economic considerations coalesced around the Shīʿī identity, broadening its sphere of activity. The emergence of political Shi’ism at this stage is thus characterized both by the increase in its influence and numbers and by its sudden and rapid growth thereafter.

Umayyad And ʿAbbāsid Period

The ʿAbbāsid era (750–945) witnessed consolidation of the Shīʿī identity. During the first twenty years of Umayyad rule under Muʿāwiyah, Ḥasan, the elder son of ʿAlī who was acclaimed caliph by the majority of the Muslims, was forced to abdicate. Some of the ardent supporters of the Shīʿī cause were executed, cursing ʿAlī from pulpits all over the empire was proclaimed by the governors to be an official duty, and the Shīʿa were oppressed and terrorized. But the single event that crystallized the nature of official Shi’ism was the martyrdom of Ḥusayn in 681 at Karbala. Ḥusayn, the only surviving grandson of the Prophet and the focus of Shīʿī aspirations, along with eighteen male members of his family and many companions, was brutally killed, and the women and children of his caravan were made captives to be humiliated in the markets and courts of Kufa and Damascus.

The tragedy of Karbala became the most effective agent in the propagation of Shi’ism. It gave to Shīʿī Islam its ethos of passion, in expressing the love (walāyah) for ahl al-bayt and a willingness to suffer persecution for the sake of justice and piety. Within a year, the tragedy gave rise to a movement known as Tawwābūn (Penitents), three thousand of whom sacrificed their lives fighting the overwhelming force of the Umayyads in repentance for their inability to help Husayn in his hour of trial. This passionate act of self-sacrifice took place without a leader from among the ahl al-bayt and thus marks the emergence of Shi’ism as an independent and self-sustaining movement.

The death of Ḥusayn and the quiescent attitude of his only surviving son, ʿAlī Zayn al-ʿĀbidīn, however, marked the first conflict over the leadership of the followers of the ahl al-bayt and their division into various groups. The Shīʿah in Kufa, especially the mawālī (the non-Arabs and the downtrodden masses) wanted an active movement which could relieve them from the oppressive rule of the Umayyads. Mukhtār ibn Abī ʿUbaydah al-Thaqafī, a Shīʿah activist, began to promote ʿAlī’s third son, Muḥammad ibn al-Ḥanafīyah, born of a Ḥanafī woman, as the Mahdī, who would save the people from oppression. This is the first recorded reference to the Mahdī. The Shīʿah saw a ray of hope in the messianic role advocated by Mukhtār for Ibn al-Ḥanafīyah, and they followed him as their Imam-Mahdī, abandoning Zayn al-ʿĀbidīn. Mukhtār’s uprising was put down in 686, and Mukhtār himself was killed, but the propaganda on behalf of Ibn al-Ḥanafīyah continued, and when he died in 700 a group of his followers, known as Kaysanīyah, believed that he had not died but had gone into “occultation” or been “hidden” and would return. The idea of the Mahdī, often equated with the Imam, and the concepts of ghaybah (occultation) and rajʿah (return) thus became integral to Shīʿī thought.

After Mukhtār’s uprising, the first ʿAlid of the Ḥusaynid line who rose against the Umayyads was Zayd, the second son of Zayn al-ʿĀbidīn. Zayd and his followers wanted no quiescent or Hidden Imam, like al-Bāqir and Ibn al-Ḥanafīyah. In their eyes, the imam, although he had to be a descendant of ʿAlī and Fāṭimah, could not claim allegiance unless he asserted his imamate publicly and, if necessary, fought for it. Zayd’s activist policy toward the imāmate and his adoption of the rationalist Muʿtazilah theological doctrines secured him Shīʿī support, and his acceptance of the legitimacy of the first two caliphs gained him the full sympathy of traditionalist circles. Zayd’s revolt, however, was unsuccessful. He and many of his followers were killed in 740, and his son Yahyā, who continued his father’s activities for three years, met the same fate in 743.

After the collapse of Zayd’s revolt, the only serious Shīʿī uprising to take place during the Umayyad period was that of the ʿAbbāsids, which began as a manifestation of the Shīʿī cause. The agents of the ʿAbbāsids called the people to rise in the name of an imam to be chosen from among the ahl al-bayt. To the extremists of the Kaysanīyah — the followers of Ibn al-Ḥanafīyah and his son Abū Hashīm — the activists of the Zaydīyah, and the other groups of the Shīʿah, this implied an ʿAlid, so they supported the ʿAbbāsids wholeheartedly. The ʿAbbāsids thus succeeded in overthrowing the Umayyad regime. Once in power, they realized that the Shīʿah would not accept them as legitimate rulers, so they turned to the ahl al-ḥadīth (people of the ḥadīth, i.e., Sunnīs) for their religious support and began to persecute the Shīʿah. The series of Zaydī revolts, particularly among ʿAlids of the Ḥasanid line, which had begun toward the end of the Umayyad era, continued into the ʿAbbāsid period. Muḥammad al-Nafs al-Zakīyah, a great-grandson of Ḥasan who had long coveted the role of Mahdī for himself, rose against the ʿAbbāsids, but he and his brother Ibrāhīm were defeated and killed in 762. Some of al-Nafs al-Zakīyah’s followers believed that he was not dead but had gone into occultation and would return.

During the formative phase of Shiism, three major trends of thought — activism, extremism, and legitimism — dominated the Shīʿī perception of the imamate. For the early period, however, it is difficult to identify well-organized groups representing each of these trends, as there was considerable overlap among their beliefs. Activists like the Kaysanīyah, for example, sometimes adopted extremist ideas. The extremists, known as ghulāt (exaggerators) because of their ascription of divinity to the Imams, often resorted to activist methods. But the ghulāt, who were identified as Shīʿah by Sunnī scholars of heresy, remained a minority that was rejected by the main body of the Shīʿah condemned by their Imams. In the course of history, however, extremists and other small branches died out or were merged into the three main branches which have survived into the twenty-first century.

The Zaydīyah, followers of Zayd ibn ʿAlī ibn al-Ḥusayn, are mainly in Yemen with smaller numbers in Iraq and parts of Africa. They represent the activist groups of the early Shīʿah, as Zayd believed that the Imam ought to be a ruler of the state and therefore must fight for his rights.

The Ismāʿīlīyah, named after Ismāʿīl, the eldest son of Imam Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq, who predeceased his father, declared Ismāʿīl’s son Muḥammad to be their seventh Imam, instead of following Jaʿfar’s second son, Mūsā al-Kāẓim. The Ismāʿīlīyah are also known as the Bāṭinīyah (the internal), that is, those who maintained the central role of the esoteric aspects of Islamic revelation in their religious system. Ismāʿīlīs occasionally rose to great political and religious prominence, and they founded the Fāṭimid Empire (909–1171).The majority of the Shīʿah belong to the Twelvers, the Ithnā ʿAsharīyah, whose theological position is regarded as moderate. They represent the legitimist or central body of the Shīʿa who believe in twelve Imams beginning with ʿAlī, followed by his two sons, Ḥasan and Ḥusayn, as the second and the third Imams, respectively. After Ḥusayn, according to Twelver Shīʿah, the imamate remained with his descendants until it reached the twelfth Imam, Muḥammad al-Mahdī, who went into occultation to return at the end of time as the messianic Imam to restore justice and equity on earth.

The consolidation of the Ithnā ʿAsharī position was accomplished by Imam Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq, the sixth Imam of the quiescent Ḥusaynid branch, who expounded his theory of the imamate based on naṣ, the explicit designation of his successor by the previous Imam, and the special knowledge of religion passed down in the family from generation to generation. With the efforts of Jaʿfar, the quiescent line of the Ḥusaynid Imams regained the prominence it had lost after the death of Ḥusayn. Jaʿfar was surrounded by traditionalists who played an important role in establishing the Shīʿī legal and theological system. By the time of Jaʿfar’s death in 765, the Shīʿa (later to become the Twelvers) were fully equipped in all branches of religion and had acquired a distinctive character. The remaining six Imams of the Twelvers’ line living under the ʿAbbāsids in varying circumstances further strengthened Imami Shiism until the twelfth Imam, Muḥammad al-Mahdī, went into occultation.

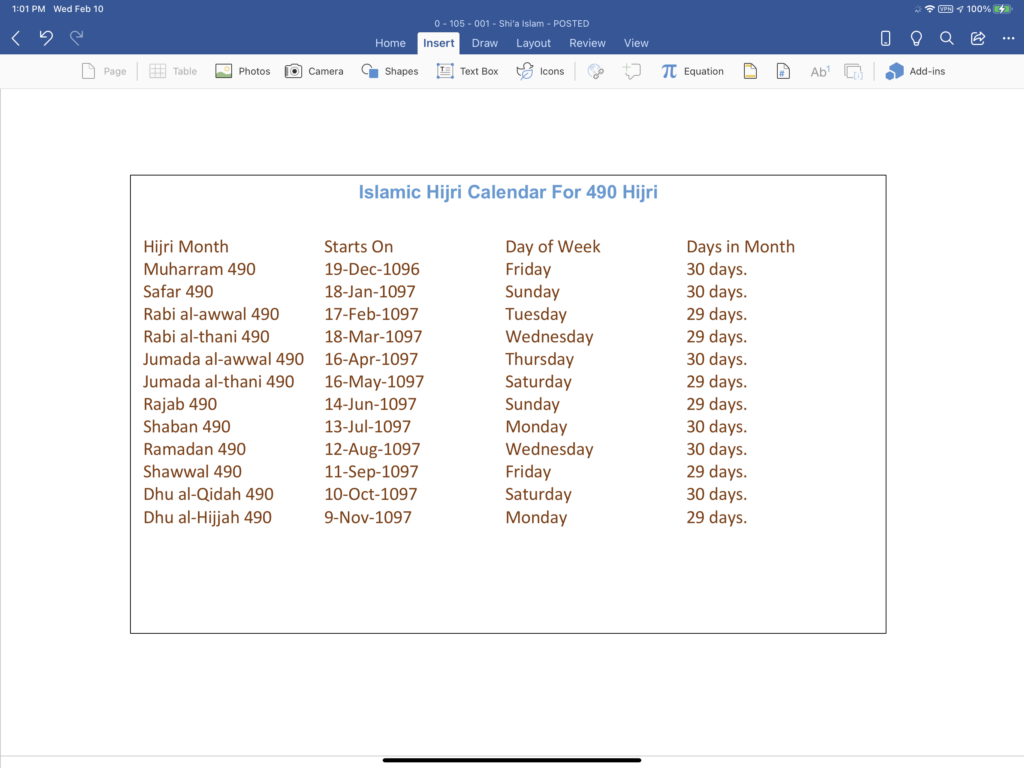

Būyid Period

| Islamic Hijri Calendar For 490 Hijri Hijri Month Starts On Day of Week Days in MonthMuharram 490 19-Dec-1096 Friday 30 days.Safar 490 18-Jan-1097 Sunday 30 days.Rabi al-awwal 490 17-Feb-1097 Tuesday 29 days.Rabi al-thani 490 18-Mar-1097 Wednesday 29 days.Jumada al-awwal 490 16-Apr-1097 Thursday 30 days.Jumada al-thani 490 16-May-1097 Saturday 29 days.Rajab 490 14-Jun-1097 Sunday 29 days.Shaban 490 13-Jul-1097 Monday 30 days.Ramadan 490 12-Aug-1097 Wednesday 30 days.Shawwal 490 11-Sep-1097 Friday 29 days.Dhu al-Qidah 490 10-Oct-1097 Saturday 30 days.Dhu al-Hijjah 490 9-Nov-1097 Monday 29 days. |

The Būyids (945–1055) accorded the Shīʿa the most favorable conditions for elaboration and standardization of their tenets. In this period compilation of the major collections of Shīʿa ḥadīth and formulation of Shīʿa law took place. This elaboration began with Muḥammad ibn Yaʿqūb al-Kulaynī (d. 1097 AD), author of the monumental Uṣūl al-kāfī (the sufficient fundamentals), who was followed by such figures as Ibn Babuyah, also called Shaykh al-Sadug (d. 991), Shaykh al-Midid (d. 1022), and Shaykh al-Ta’ifah, or Muhammad ibn al-Hasan al-Tutsi (d. 1067), by whom the principal doctrinal works of Shi’i theology and religious sciences we’re fine ally established. This was also the period of other renowned Shi’i scholars, such as al-Sharif al-Radi (d. 1015) – who complied the sermons and sayings of Ali – and his brother, Murtada ‘Alam al-Huda (d. 1044).

These intellectual activities continued after the fall of the Būyids through such Shīʿī scholars as Faḍl al-Ṭabarsī (d. 1153), known for his monumental Qurʿānic commentary; Raḍī al-Dīn ʿAlī ibn al-Ta’us (d. 1266), theologian and gnostic; Naṣīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī (d. 1273); ʿAllāmah Ḥillī (d. 1326); and Ḥaydar al-Āmulī (d. after 1385), who established a new system of rational theology.

It was also in the Būyid period that two popular Shīʿī commemorations were instituted in Baghdad: ʿAshūrāʿ, marking the martyrdom of Imam Ḥusayn on the tenth of the month Muḥarram, which was observed with great religious fervor and zeal; and the Festival of Ghadīr, commemorating the Prophet’s nomination of ʿAlī as his successor at Ghadīr al-Khumm. It was also during this period that public mourning ceremonies for Ḥusayn were initiated, shrines were built for the Imams, and the custom of pilgrimage to these shrines was more popularly established.

By the end of the Būyid era Shiism’s basic beliefs had been completely formulated, leaving to the future only elaborations, interpretations, rationalizations, and certain adaptations and additions. Among the scholars who have enriched Shīʿī literature over the past eight hundred years—especially in philosophy, theology, and law during the Mongol, Ṣafavid, and Qājār periods—were such great figures of the Ṣafavid period as Mīr Dāmād (d. 1631) and Mullā Ṣadrā (d. 1640), masters of metaphysics with whom Islamic philosophy reached a new peak; Bahā’ al-Dīn al-ʿĀmilī, theologian and mathematician; and the two Majlisīs, the second, Muḥammad Bāqir, being the author of the largest compendium of the Shīʿī sciences, the Biḥār al-anwār (Oceans of Light).

Although Ithnā ʿAsharī Shiism attained its final position under the Būyids who ruled over Baghdad and Iran, the Ismāʿīlīyah and the Zaydīyah also consolidated their doctrinal positions at roughly the same time. The Ismāʿīlīs controlled Egypt, southern Syria, much of North Africa, and the Hejaz, and the Zaydīs established their rule in northern Iran and Yemen. This political supremacy provided the Ismāʿīlīyah and the Zaydīyah with opportunities to elaborate and standardize their doctrinal positions. By the end of the tenth century, all three branches of Shi’ism were thus firmly enough established to withstand the vicissitudes of history and the stresses of the sectarian role into which they were pushed by the Sunnī majority.

105 – 001

Last Update: 02/2021

See COPYRIGHT information below.