Islam – Part III: Islamic Denominations

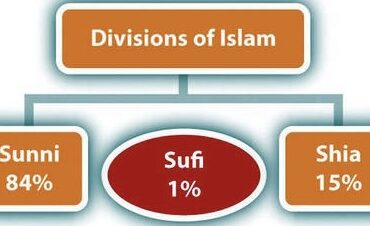

An overview of the major schools and branches of Islam:

SUNNI

Sunni Schools Of Law – Jurisprudence

- Hanafi

- Maliki

- Shafi‘i

- Hanbali

Others

- Zahiri

- Awza’i

- Thawri

- Laythi

- Jariri

Sunni Schools Of Theology

- Ash’ari

- Maturidi

- Traditionalist

- Others

- Muʿtazila

- Murji’ah

The largest denomination in Islam is Sunni Islam, which makes up 75–90 percent of all Muslims and is arguably the world’s largest religious denomination. Sunni Muslims also go by the name Ahl as-Sunnah which means “people of the tradition [of Muhammad].”

Sunnis believe that the first four caliphs were the rightful successors to Muhammad; since Allah did not specify any particular leaders to succeed him and those leaders were elected. Sunnis believe that anyone who is righteous and just could be a caliph but they have to act according to the Qur’an and the Hadith, the example of Muhammad and give the people their rights.

The Sunnis follow the Qur’an and the Hadith, which are recorded in Sunni traditions known as Al-Kutub Al-Sittah (six major books). For legal matters derived from the Qur’an or the Hadith, many follow four Sunni madh’habs (schools of thought):

- Hanafi;

- Hanbali;

- Maliki; and,

- Shafi’i.

All four accept the validity of the others and a Muslim may choose any one that he or she finds agreeable.

Sunni schools of theology encompass Ashʿarirism founded by Al-Ashʿarī (c. 874–936), Maturidi by Abu Mansur al-Maturidi (853–944 A.D.) and Traditionalist theology under the leadership of Ahmad ibn Hanbal (780–855 CE). Traditionalist theology is characterized by its adherence to a literal understanding of the Qur’an and the Sunnah, the belief in the Qur’an to be uncreated and eternal, and opposes reason (kalam) in religious matters. On the other hand, Maturidism asserted that good and evil can be understand by reason alone. Maturidi’s doctrine, based on Hanafi-law, asserted man’s capacity and will alongside the supremacy of Allah in man’s acts, providing a doctrinal framework for more flexibility, adaptability and syncretism. Maturidism especially flourished in Central-Asia. Nevertheless, people would relay on revelation, because reason alone could not grasp the whole truth. Asharism holds, ethics can just derive from divine revelation, but not from human reason. However, Asharism accepts reason in regard of exegetical matters and combined Muʿtazila approaches with traditionalistic ideas.

In the 18th century, Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab led a Salafi movement, referred by outsiders as Wahhabism, in modern-day Saudi Arabia. Originally shaped Hanbalism, many modern followers departed from any of the established four schools of law Hanafi, Shafi, Maliki, and Hanbali. Similarly, Ahl al-Hadith is a movement that deemphasized sources of jurisprudence outside the Qur’an and hadith, such as informed opinion (ra’y). The Deobandi movement is a reformist movement originating in South Asia, influenced by the Wahhabi movement.

SHI’A

The Shi’a constitute 5–15 percent of Islam and are its second-largest branch.

The Imam Hussein Shrine in Karbala, Iraq is a holy site for Shi’a Muslims.

While the Sunnis believe that a Caliph should be elected by the community, Shi’a’s believe that Muhammad appointed his son-in-law, Ali ibn Abi Talib, as his successor and only certain descendants of Ali could be Imams. As a result, they believe that Ali ibn Abi Talib was the first Imam (leader), rejecting the legitimacy of the previous Muslim caliphs Abu Bakr, Uthman ibn al-Affan and Umar ibn al-Khattab. Other points of contention include certain practices viewed as innovating the religion, such as the mourning practice of tatbir, and the cursing of figures revered by Sunnis. However, Jafar al-Sadiq himself disapproved of people who disapproved of his great grand father Abu Bakr and Zayd ibn Ali revered Abu Bakr and Umar. More recently, Grand Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani condemned the practice.

Shi’a Islam has several branches, the most prominent being the Twelvers (the largest branch), Zaidis and Ismailis. Different branches accept different descendants of Ali as Imams. After the death of Imam Jafar al-Sadiq who is considered the sixth Imam by the Twelvers and the Ismaili’s, the Ismailis recognized his son Isma’il ibn Jafar as his successor whereas the Twelver Shi’a’s (Ithna Asheri) followed his other son Musa al-Kadhim as the seventh Imam. The Zaydis consider Zayd ibn Ali, the uncle of Imam Jafar al-Sadiq, as their fifth Imam, and follow a different line of succession after him. Other smaller groups include the Bohra as well as the Alawites and Alevi. Some Shi’a branches label other Shi’a branches that do not agree with their doctrine as Ghulat.

Other Denominations

- Ahmadiyya is an Islamic reform movement (with Sunni roots) founded by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad that began in India in 1889 and is practiced by 10 to 20 million Muslims around the world. Ahmad claimed to have fulfilled the prophecies concerning the arrival of the ‘Imam Mahdi’ and the ‘Promised Messiah’.

- Bektashi Alevism is a syncretic and heterodox local Islamic tradition, whose adherents follow the mystical (bāṭenī) teachings of Ali and Haji Bektash Veli. Alevism incorporates Turkish beliefs present during the 14th century, such as Shamanism and Animism, mixed with Shi’as and Sufi beliefs, adopted by some Turkish tribes.

- The Ibadi is a sect that dates back to the early days of Islam and is a branch of Kharijite and is practiced by 1.45 million Muslims around the world. Unlike most Kharijite groups, Ibadism does not regard sinful Muslims as unbelievers.

- Mahdavia is an Islamic sect that believes in a 15th-century Mahdi, Muhammad Jaunpuri.

- The Qur’anists are Muslims who generally reject the Hadith.

Non-Denominational Muslims

Non-denominational Muslims is an umbrella term that has been used for and by Muslims who do not belong to or do not self-identify with a specific Islamic denomination. Prominent figures who refused to identify with a particular Islamic denomination have included Jamal ad-Din al-Afghani, Muhammad Iqbal, and Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Recent surveys report that large proportions of Muslims in some parts of the world self-identify as “just Muslim,” although there is little published analysis available regarding the motivations underlying this response. The Pew Research Center reports that respondents self-identifying as “just Muslim” make up a majority of Muslims in seven countries (and a plurality in three others), with the highest proportion in Kazakhstan at 74 percent. At least one in five Muslims in at least 22 countries self-identify in this way.

Derived Religions

Some movements, such as the Druze, Berghouata and Ha-Mim, either emerged from Islam or came to share certain beliefs with Islam and whether each is separate a religion or a sect of Islam is sometimes controversial. Yazdânism is seen as a blend of local Kurdish beliefs and Islamic Sufi doctrine introduced to Kurdistan by Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir in the 12th century. Bábism stems from Twelver Shi’a passed through Siyyid ‘Ali Muhammad i-Shirazi al-Bab while one of his followers Mirza Husayn ‘Ali Nuri Baha’u’llah founded the Bahai Faith. Sikhism, founded by Guru Nanak in late-fifteenth-century Punjab, incorporates aspects of both Islam and Hinduism. African American Muslim movements include the Nation of Islam, Five-Percent Nation and Moorish scientists.

Demographics

World Muslim Population By Percentage

(Reported by the Pew Foundation)

A comprehensive 2015 demographic study of 232 countries and territories reported that 24 percent of the global population, or 1.8 billion people, are Muslims. Of those, it is estimated that over 75–90 percent are Sunni and 10–20 percent are Shi’a with a small minority belonging to other sects. Approximately 57 countries are Muslim-majority, and Arabs account for around 20 percent of all Muslims worldwide. The number of Muslims worldwide increased from 200 million in 1900 to 551 million in 1970, and tripled to 1.8 billion by 2015.

The majority of Muslims live in Asia and Africa. Approximately 62 percent of the world’s Muslims live in Asia, with over 683 million adherents in Indonesia, Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh. In the Middle East, non-Arab countries such as Turkey and Iran are the largest Muslim-majority countries; in Africa, Egypt and Nigeria have the most populous Muslim communities.

Most estimates indicate that China has approximately 20 to 30 million Muslims (1.5 percent to 2 percent of the population). However, data provided by the San Diego State University’s International Population Center to U.S. News & World Report suggests that China has 65.3 million Muslims. Islam is the second largest religion after Christianity in many European countries, and is slowly catching up to that status in the Americas, with between 2,454,000, according to Pew Forum, and approximately seven million Muslims, according to the Council on American–Islamic Relations (CAIR), in the United States.

According to the Pew Research Center, Islam is set to equal Christianity worldwide in number of adherents by the year 2050. Islam is set to grow faster than any other major world religion, reaching a total number of 2.76 billion (an increase of 73 percent). Causes of this trend involve high fertility rates as a factor, with Muslims having a rate of 3.1 compared to the world average of 2.5, and the minimum replacement level for a population at 2.1. Another factor is also due to fact that Islam has the highest number of adherents under the age of 15 (34 percent of the total religion) of any major religion, compared with Christianity’s 27 percent. Sixty percent of Muslims are between the ages of 16 and 59, while only seven percent are aged 60+ (the smallest percentage of any major religion). Countries such as Nigeria and North Macedonia are expected to have Muslim majorities by 2050. In India, the Muslim population will be larger than any other country.

Culture

The term “Islamic culture” could be used to mean aspects of culture that pertain to the religion, such as festivals and dress code. It is also controversially used to denote the cultural aspects of traditionally Muslim people. Finally, “Islamic civilization” may also refer to the aspects of the synthesized culture of the early Caliphates, including that of non-Muslims, sometimes referred to as “Islamicate.”

Jakarta, capital of Indonesia, the most populous Muslim-majority country.

Architecture

Perhaps the most important expression of Islamic architecture is that of the mosque. Varying cultures have an effect on mosque architecture. For example, North African and Spanish Islamic architecture such as the Great Mosque of Kairouan contain marble and porphyry columns from Roman and Byzantine buildings, while mosques in Indonesia often have multi-tiered roofs from local Javanese styles.

Islamic Art

Islamic art encompasses the visual arts produced from the 7th century onwards by people (not necessarily Muslim) who lived within the territory that was inhabited by Muslim populations. It includes fields as varied as architecture, calligraphy, painting, and ceramics, among others.

While not condemned in the Qur’an, making images of human beings and animals is frowned on in many Islamic cultures and connected with laws against idolatry common to all Abrahamic religions, as ‘Abdullaah ibn Mas’ood reported that Muhammad said, “Those who will be most severely punished by Allah on the Day of Resurrection will be the image-makers” (reported by al-Bukhaari, see al-Fath, 10/382). However this rule has been interpreted in different ways by different scholars and in different historical periods, and there are examples of paintings of both animals and humans in Mughal, Persian and Turkish art. The existence of this aversion to creating images of animate beings has been used to explain the prevalence of calligraphy, tessellation and pattern as key aspects of Islamic artistic culture.

Calendar

The phases of the Moon form the basis for the Islamic calendar

The formal beginning of the Muslim era was chosen, reportedly by Caliph Umar, to be the Hijra in 622 A.D., which was an important turning point in Muhammad’s fortunes. It is a lunar calendar with days lasting from sunset to sunset. Islamic holy days fall on fixed dates of the lunar calendar, which means that they occur in different seasons in different years in the Gregorian calendar. The most important Islamic festivals are Eid al-Fitr on the 1st of Shawwal, marking the end of the fasting month Ramadan, and Eid al-Adha on the 10th of Dhu al-Hijjah, coinciding with the end of the Hajj pilgrimage.

Criticism Of Islam

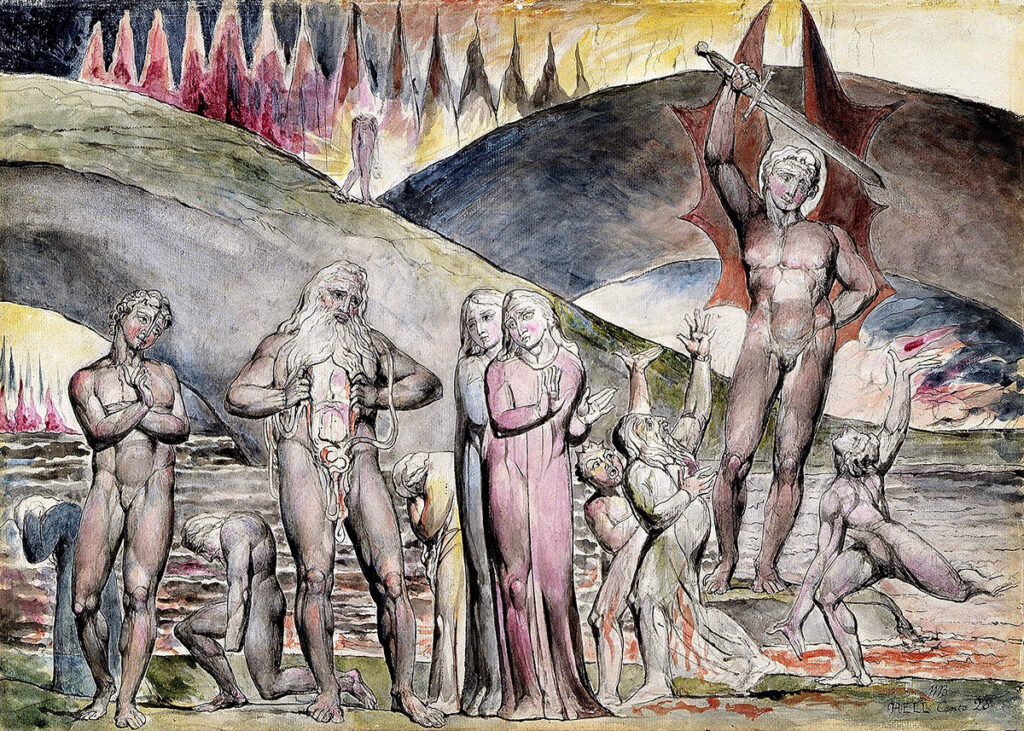

William Blake’s illustration of Inferno (19th century) shows Muhammad pulling his chest open which has been sliced by a devil to symbolize his role as a “false prophet.”

Criticism of Islam has existed since Islam’s formative stages. Early criticism came from Christian authors, many of whom viewed Islam as a Christian heresy or a form of idolatry and often explained it in apocalyptic terms. Later there appeared criticism from the Muslim world itself, and also from Jewish writers and from ecclesiastical Christians. Issues relating to the authenticity and morality of the Qur’an, the Islamic holy book, are also discussed by critics.

Defamatory images of Muhammad, derived from early 7th century depictions of Byzantine Church, appear in the 14th-century epic poem Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri. Here, Muhammad appears in the eighth circle of hell, along with Ali. Dante does not blame Islam as a whole, but accuses Muhammad of schism, by establishing another religion after Christianity. Otherwise the Greek Orthodox Bishop Paul of Antioch accepts Muhammed as a prophet, but not that his mission was universal. Since the law of Christ is superior to the law of Islam, Muhammad was only ordered to the Arabs, whom a prophet was not sent yet.

Apologetic writings, attributed to Abdullah Ibn al-Muqaffa, not only defended Manichaeism against Islam, but also criticized the Islamic concept of Allah. Accordingly, the Qur’anic deity was disregarded as an unjust, tyrannic, irrational and malevolent demonic entity, who “fights with humans and boasts about His victories” and “sitting on a throne, from which He descends.”

Since the events of September 11, 2001, Islam has faced criticism over its scriptures and teachings being a significant source of terrorism and terrorist ideology.

Other criticisms focus on the question of human rights in modern Muslim-majority countries, and the treatment of women in Islamic law and practice. In wake of the recent multiculturalism trend, Islam’s influence on the ability of Muslim immigrants in the West to assimilate has been criticized. Both in his public and personal life, others objected the morality of Muhammad, therefore also the sunnah as a role-model.

Tatars Tengrists, criticize Islam as a semitic religion, which forced Turks to submission to an alien culture. Submission and humility, two significant components of Islamic spirituality, are disregarded as major failings of Islam, not as virtues. Further, since Islam mentions semitic history as if it were the history of all mankind, but disregards components of other cultures and spirituality, the international approach of Islam is seen as a threat. It additionally gives Imams an opportunity to march against their own people under the banner of international Islam.

101 – 002-c

https://discerning-Islam.org

Last Update: 02/2021

See COPYRIGHT information below.